By Louis ‘Barok’ C Biraogo — August 30, 2024

CAN the International Criminal Court (ICC) really hold the Philippines accountable for alleged crimes against humanity? That’s the question at the heart of the ongoing legal debate surrounding the ICC’s authority to issue and enforce arrest warrants in the Philippines. At the center of this debate are two prominent figures: Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla and Solicitor General Menardo Guevarra, each holding divergent views on how the Philippines should respond to the ICC’s ongoing investigation into alleged crimes against humanity committed during former President Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs.

Remulla’s Stance: Sovereignty and National Jurisdiction

Justice Secretary Remulla asserts that any attempt by the ICC to enforce arrest warrants in the Philippines must first secure approval from Philippine courts. Remulla’s position is grounded in the principle of national sovereignty, suggesting that the enforcement of international legal decisions within the Philippines cannot occur without the country’s express consent through its judicial system. He argues that the Philippines, having withdrawn from the Rome Statute in 2019, is no longer under any obligation to cooperate with the ICC, especially in terms of arresting individuals implicated in the ICC’s investigations.

Arguments in Favor of Remulla’s Position:

- National Sovereignty and Jurisdiction: The principle of state sovereignty under international law supports Remulla’s stance that the enforcement of an ICC warrant within the Philippines must respect the country’s judicial processes. Article 2(1) of the United Nations Charter emphasizes the sovereignty of member states, which could be interpreted to mean that the ICC must respect the Philippines’ decision to enforce or not enforce its warrants.

- Philippines’ Withdrawal from the Rome Statute: The Philippines’ withdrawal from the Rome Statute in 2019 potentially negates any obligation to cooperate with the ICC. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) supports the idea that a state’s withdrawal from a treaty absolves it from future obligations under that treaty, unless the treaty specifies otherwise.

- Domestic Legal Framework: Remulla’s argument is further bolstered by the notion that the Philippines possesses a robust legal system capable of prosecuting crimes, including those related to the drug war. According to Article 17 of the Rome Statute, the ICC acts as a court of last resort, intervening only when national legal systems are unwilling or unable to prosecute serious crimes.

Arguments Against Remulla’s Position:

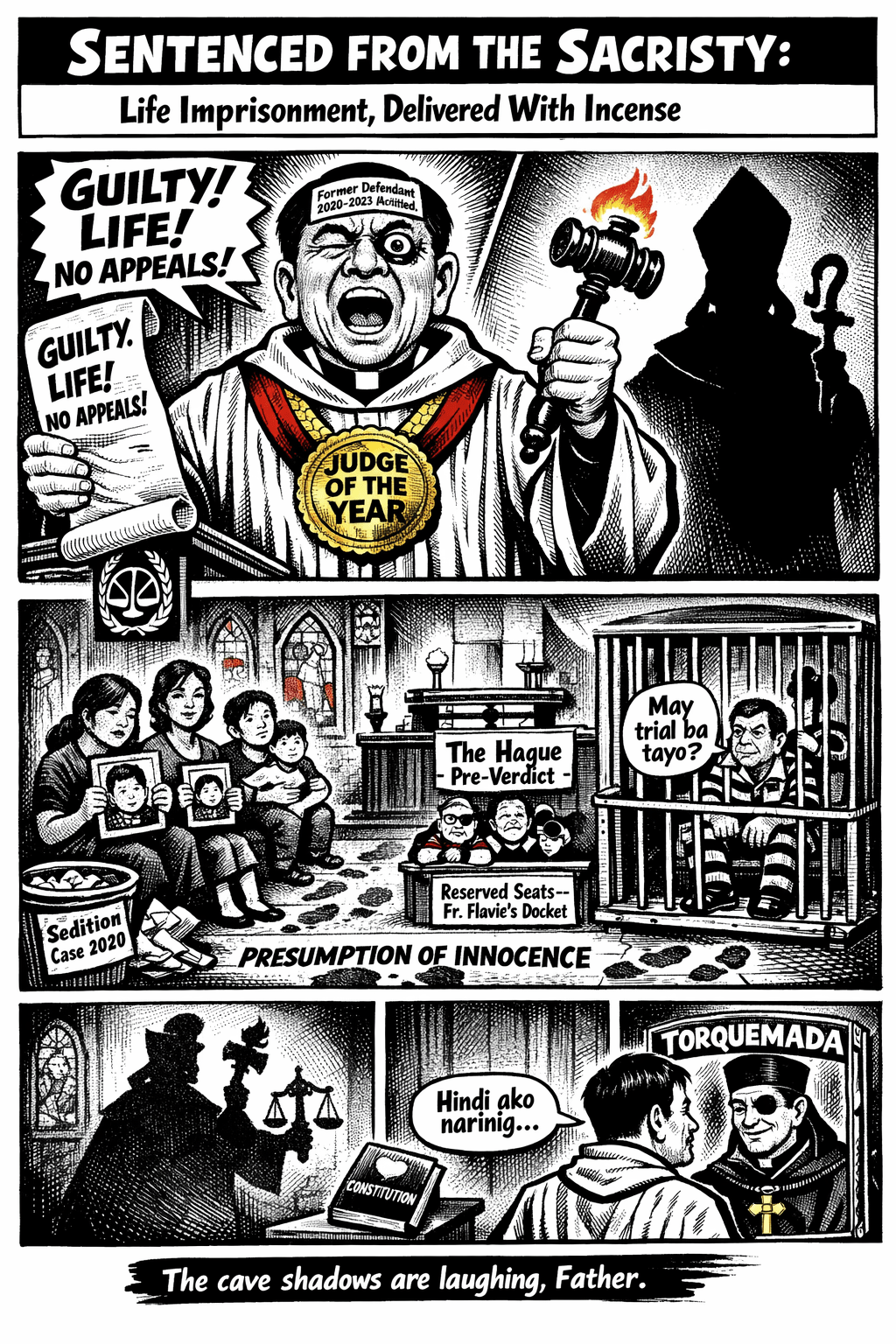

- Continued ICC Jurisdiction: Despite the Philippines’ withdrawal from the Rome Statute, the ICC retains jurisdiction over crimes committed during the country’s membership. Article 127(2) of the Rome Statute clearly states that withdrawal does not affect any proceedings already underway prior to the withdrawal taking effect, thus binding the Philippines to cooperate with ongoing investigations.

- Principle of Complementarity: The ICC’s mandate is to complement, not replace, national judicial systems. The court intervenes only when a country is unwilling or unable to prosecute international crimes. The absence of meaningful investigations and prosecutions in the Philippines regarding the drug war killings suggests a potential failure of the national legal system, justifying the ICC’s involvement.

- International Obligations: The Philippines remains bound by certain international obligations, even outside the Rome Statute. Customary international law, as well as other treaties to which the Philippines is a party, requires cooperation with international mechanisms for accountability, particularly in addressing serious human rights violations.

Guevarra’s Stance: ICC Independence and International Law

On the other side of the debate, Solicitor General Guevarra contends that the ICC does not require approval from Philippine courts to issue or enforce its arrest warrants. Guevarra’s view aligns with the legal framework of the ICC, which operates independently of national courts. He argues that the ICC’s authority to issue arrest warrants comes directly from the Rome Statute, which the Philippines ratified and was bound by during the period in question.

Arguments in Favor of Guevarra’s Position:

- ICC’s Independent Authority: The Rome Statute, particularly Article 58, grants the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber the power to issue arrest warrants. This authority is independent of national courts, ensuring that the ICC can act without needing the approval of the states involved.

- International Legal Precedents: Precedents from other international tribunals, such as the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), support the view that international courts can issue and enforce warrants without the need for local court approval. These tribunals have successfully conducted prosecutions even when faced with non-cooperative states.

- Legal Continuity Post-Withdrawal: As per Article 127(2) of the Rome Statute, the ICC retains jurisdiction over crimes that occurred during the Philippines’ membership period. The withdrawal does not negate ongoing investigations or the court’s ability to issue warrants related to those investigations.

Arguments Against Guevarra’s Position:

- Challenges to Enforcement: While the ICC can issue warrants independently, the actual enforcement of these warrants typically requires the cooperation of state parties. Without the cooperation of Philippine authorities, the enforcement of ICC warrants could face significant practical hurdles, potentially rendering them ineffective within the Philippines.

- Sovereignty Concerns: Critics might argue that the ICC’s actions could infringe on the Philippines’ sovereignty, particularly if it seeks to operate independently within Philippine territory without the government’s consent. This could lead to tensions between international legal norms and national sovereignty.

- Domestic Legal Remedies: While Guevarra acknowledges that individuals subject to ICC warrants can challenge them in local courts, this approach still relies on the effectiveness of the Philippine judicial system, which Remulla asserts is capable of handling such cases domestically.

A Balanced View: Who Holds the Advantage?

Between the two, Guevarra’s stance appears to hold a stronger legal foundation. The Rome Statute and international legal precedents support the ICC’s independent authority to issue and enforce arrest warrants, even in non-cooperative states. The continued jurisdiction of the ICC over crimes committed during the Philippines’ membership period, coupled with the principle of complementarity, reinforces the ICC’s mandate to ensure accountability for serious crimes.

However, Remulla’s arguments cannot be entirely dismissed. The enforcement of ICC warrants within the Philippines is contingent on the cooperation of the Philippine government, which, under the principle of state sovereignty, retains significant control over what occurs within its territory. Without such cooperation, the practical enforcement of ICC warrants may face insurmountable obstacles.

Recommendations

To Secretary Remulla:

- Clarify Legal Processes: Provide a clear legal framework outlining the specific procedures the ICC and Interpol would need to follow within the Philippines. This would help ensure that the government’s position is transparent and consistent with both domestic and international legal obligations.

- Strengthen Domestic Accountability Mechanisms: To reinforce the argument that the Philippines can handle these cases independently, the DOJ should intensify efforts to investigate and prosecute those responsible for the drug war killings. Demonstrating a genuine commitment to accountability would reduce the ICC’s justification for intervening.

- Prepare for International Consequences: Given the Philippines’ resistance to the ICC, be prepared for potential international repercussions, such as sanctions or diplomatic isolation. Developing a strategic response to these possibilities will be crucial in maintaining the Philippines’ international standing.

To Solicitor General Guevarra:

- Advocate for International Accountability: Continue to advocate for the enforcement of ICC warrants and the importance of international justice. Highlight the ICC’s role in preventing impunity for serious crimes and emphasize the need for the Philippines to uphold its international obligations.

- Work on Diplomatic Channels: Use diplomatic channels to negotiate the terms of cooperation with the ICC, ensuring that Philippine sovereignty is respected while upholding international law. This approach could lead to a more balanced resolution that addresses both national and international concerns.

In this complex legal landscape, the clash between Remulla and Guevarra reflects the broader tension between national sovereignty and international accountability—a tension that is likely to persist as the ICC continues its investigation into Duterte’s war on drugs.

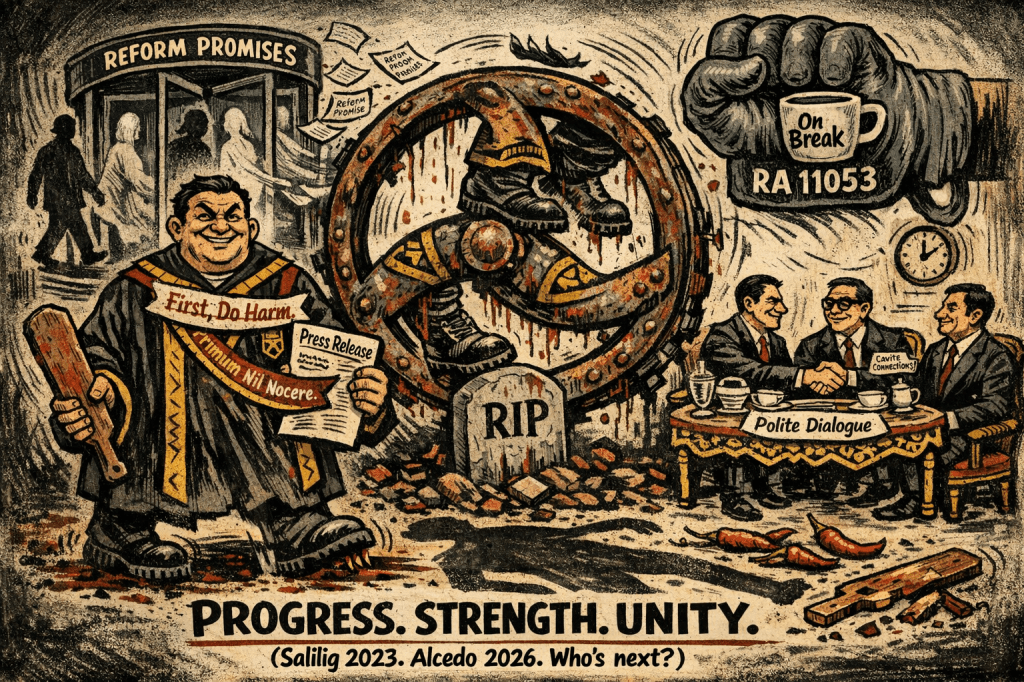

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

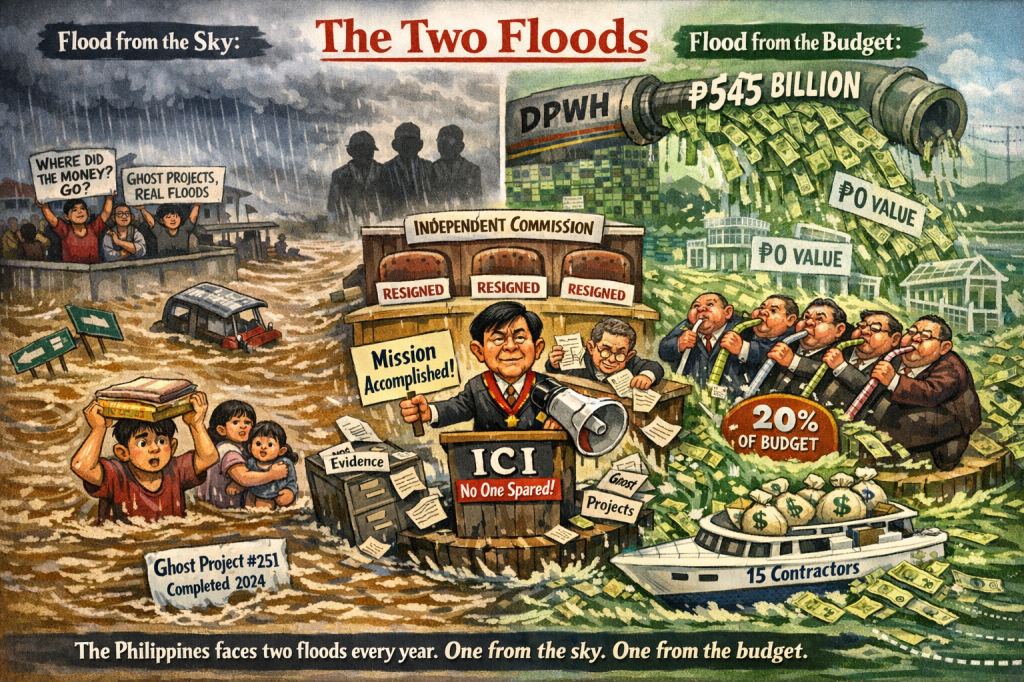

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

Leave a comment