By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — September 16, 2924

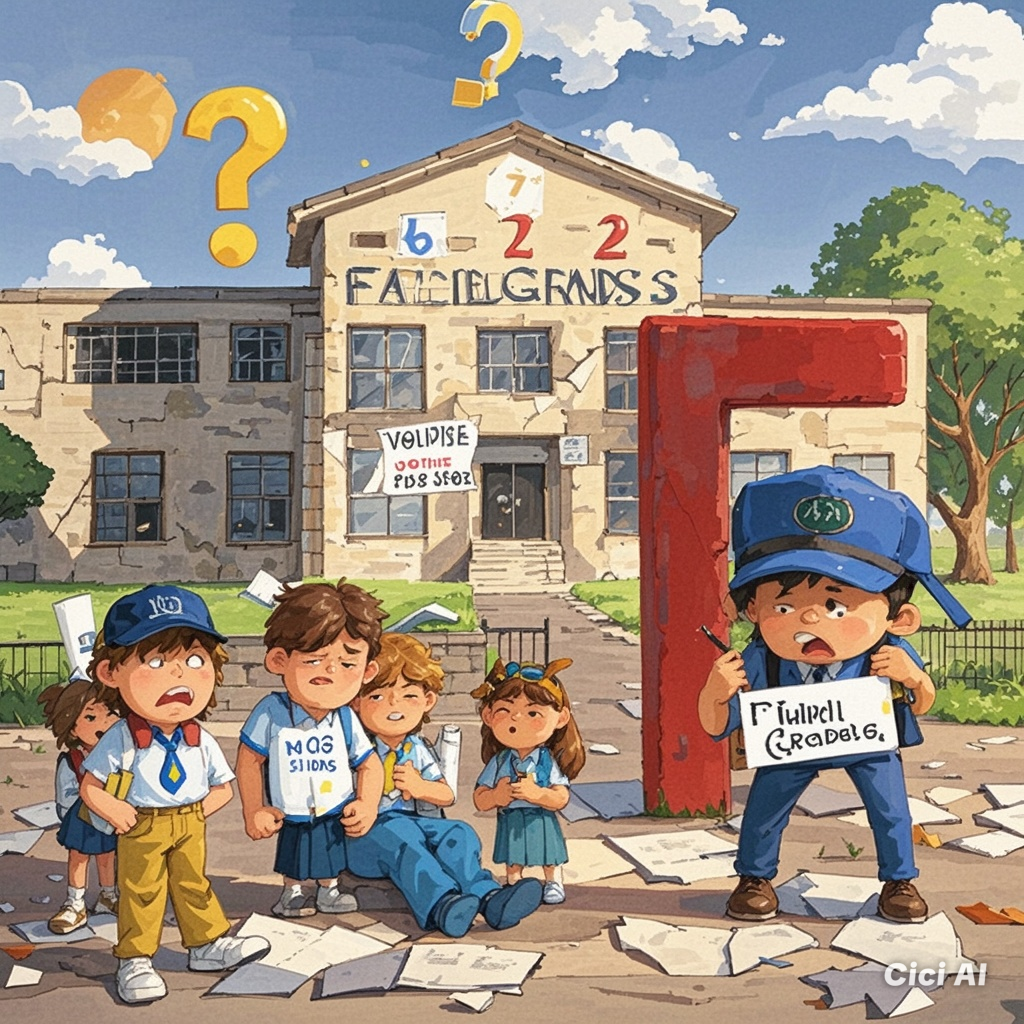

IMAGINE a nation where nearly three-quarters of students are falling behind in the most basic educational competencies—mathematics, science, reading, and even creative thinking. For the Philippines, this is not a grim dystopian tale but a harsh reality. The country’s dismal performance in the 2022 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) paints a picture of an educational system in freefall, lagging far behind its ASEAN peers like Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam. Even the brightest Filipino students only manage to match the average performers of these neighboring countries. The country’s future hangs in a precarious balance, and yet, the road to recovery remains fraught with challenges, confusion, and deeply rooted systemic issues.

At the heart of this crisis is the decline in “foundational skills”—basic literacy and numeracy, the bedrock upon which all other learning is built. The World Bank (WB) has stepped into this dire situation, proposing a series of reforms aimed at reviving the failing educational system of the Philippines. But, as with any reform, questions remain. Are these proposals enough to reverse the tide? Or are they just another patchwork solution for a problem that requires far deeper structural changes?

A System in Decline

To fully grasp the magnitude of the crisis, we must look back at how the Philippines’ education system evolved—or rather, devolved. Decades ago, the Philippines was regarded as one of the best in Southeast Asia in terms of literacy and educational attainment. But over the years, systemic neglect, underfunding, and mismanagement have eroded its quality. The educational reforms of 2012, under the “K to 12” program, aimed to modernize the system by adding two additional years to basic education. However, the focus on expansion overshadowed the critical need to improve quality, particularly in early education where foundational skills are forged.

PISA results over the past years are a clear indicator of this decline. In 2018, the Philippines ranked at the bottom in reading and math. By 2022, these numbers only slightly improved, but the gap between Filipino students and their peers in neighboring countries remained gaping. The World Bank identified a key reason for this: the country’s curriculum is overwhelmingly content-based, focusing on rote memorization rather than a competency-based approach that teaches students how to apply knowledge practically.

The World Bank’s Prescription

The World Bank’s experts, such as Diego Luna Bazaldua, propose a radical shift: move from a content-based to a competency-based curriculum, and integrate literacy and numeracy into all subjects, starting at the early grades. This approach, which has been successfully implemented in countries like Vietnam and Ireland, aims to build a stronger foundation for students, making sure they not only learn but understand and apply basic concepts.

However, curriculum reform alone won’t suffice. The World Bank’s strategy also emphasizes the importance of aligning teaching materials and, crucially, training teachers to deliver the new curriculum effectively. A long-term commitment, they stress, is essential. Quick fixes won’t work in an educational system where inequities are deeply entrenched—where children from poorer regions often lack access to quality materials, trained teachers, or even adequate learning spaces.

The ASEAN Chasm: Why Is the Philippines Falling Behind?

The reasons for the Philippines’ educational collapse are myriad. The country’s socio-economic disparities play a huge role. Students in rural and underserved areas suffer from limited access to resources, while urban students often benefit from better-funded schools. But the issues run deeper than resources alone. The mother-tongue policy—meant to bridge linguistic gaps—has only further fragmented the system, particularly in a country with over 19 major languages. And then there is the culture of rote memorization, a pedagogical relic that places emphasis on passing tests rather than fostering critical thinking.

In contrast, countries like Vietnam have made literacy and numeracy the core of their educational policy, focusing on training teachers extensively and fostering a culture of applied learning rather than memorization. The difference in approach is stark—and the results even starker.

World Bank’s Recommendations: Will They Work?

The World Bank’s proposed measures center on three key areas: focusing on foundational skills in literacy and numeracy, shifting from a content-based to a competency-based curriculum, and investing in long-term reforms. But how do these proposals measure up when tested against the practical realities of the Philippines’ educational landscape?

1. Feasibility

Shifting to a competency-based curriculum is certainly feasible, but it requires a massive overhaul—not just in curriculum design but in teacher training, material alignment, and educational infrastructure. The challenge here lies in implementation. Can the Philippines, with its limited resources and political complexities, muster the will and coordination to execute this reform?

2. Acceptability

The World Bank’s recommendations have gained the support of education reform advocates like Rep. Roman Romulo, but widespread buy-in from stakeholders, particularly teachers and local communities, is essential. Change can only succeed if it is owned by those on the frontlines—teachers and students alike.

3. Suitability

The recommendations are suitable for the Philippines’ educational needs, particularly the emphasis on foundational skills. However, the complexity of the language debate—whether to conduct learning in English, Filipino, or local dialects—remains a thorny issue.

4. Results

While it is tempting to look at Vietnam’s success and expect similar results, the Philippines’ deeply rooted systemic issues mean that improvements will take years, if not decades, to manifest fully. There is no shortcut to reversing decades of neglect.

5. Flexibility

The proposed reforms are adaptable, particularly the shift to a competency-based curriculum. But the Philippines’ diverse linguistic and socio-economic landscape requires a highly flexible approach. One-size-fits-all solutions will not work.

6. Innovation

Technology could play a pivotal role in addressing some of these challenges. From digital learning platforms to AI-driven personalized education tools, innovation could help overcome resource constraints, especially in underserved areas.

7. Sustainability

Sustaining these reforms requires not just funding but political will. Long-term commitment from successive governments is crucial. The World Bank is right to caution against quick fixes, but sustaining reforms in a country with a history of policy discontinuity remains a challenge.

8. Alignment with Values

The focus on equity—ensuring all students, regardless of socio-economic background, have access to quality foundational skills—is aligned with the country’s broader educational goals. However, reconciling this with the language of instruction debate will test these values.

9. Communication

A successful reform requires transparent and effective communication, especially with parents, teachers, and policymakers. Without a clear understanding of what these changes mean, resistance to reform could stall progress.

10. Learning

The World Bank’s emphasis on continuous learning, particularly for teachers, is key. The Philippines must build a system where teachers themselves are lifelong learners, continually adapting to new methods and technologies.

The Path Forward: Recommendations

The Philippines faces a monumental task, but all is not lost. Here’s how to proceed:

- Phased Implementation: Begin with pilot programs that focus on foundational skills in key regions before scaling nationwide.

- Teacher Training: Invest heavily in teacher development. Quality education begins with well-trained educators.

- Technology: Leverage technology to bridge resource gaps, particularly in underserved areas.

- Commitment to Equity: Target the most vulnerable regions first. Equity-focused interventions are crucial to lifting the entire system.

- Sustained Political Will: The government must commit to long-term education reform, beyond political cycles.

The Philippines stands at a crossroads. The future of its education system will be written not only in the halls of government but in the hearts and minds of every Filipino. Real change starts with every student, every classroom, every teacher—and the collective resolve to prioritize education as the cornerstone of the nation’s future.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

Leave a comment