By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — September 18, 2024

AS THE sun blazed down on Davao City, one of the most controversial figures in recent Philippine history, Lloyd Christopher Lao, was led away in handcuffs. This wasn’t just another arrest—it was a public reckoning. Years of whispered suspicions, allegations of corruption, and unanswered questions had finally culminated in this moment. And the nation, still reeling from the scandal, holds its breath to see what comes next.

The charges? Graft, as filed by the Office of the Ombudsman. But the story, as Senator Richard “Dick” Gordon emphatically points out, runs far deeper than just technical violations of the anti-graft law. It’s a saga of greed, power, and a nation brought to its knees at a time of great peril. And while the bail set at P90,000 may seem insignificant in the grand scheme, the broader implications of Lao’s alleged actions and the political machinations that shielded him for so long make this case anything but ordinary.

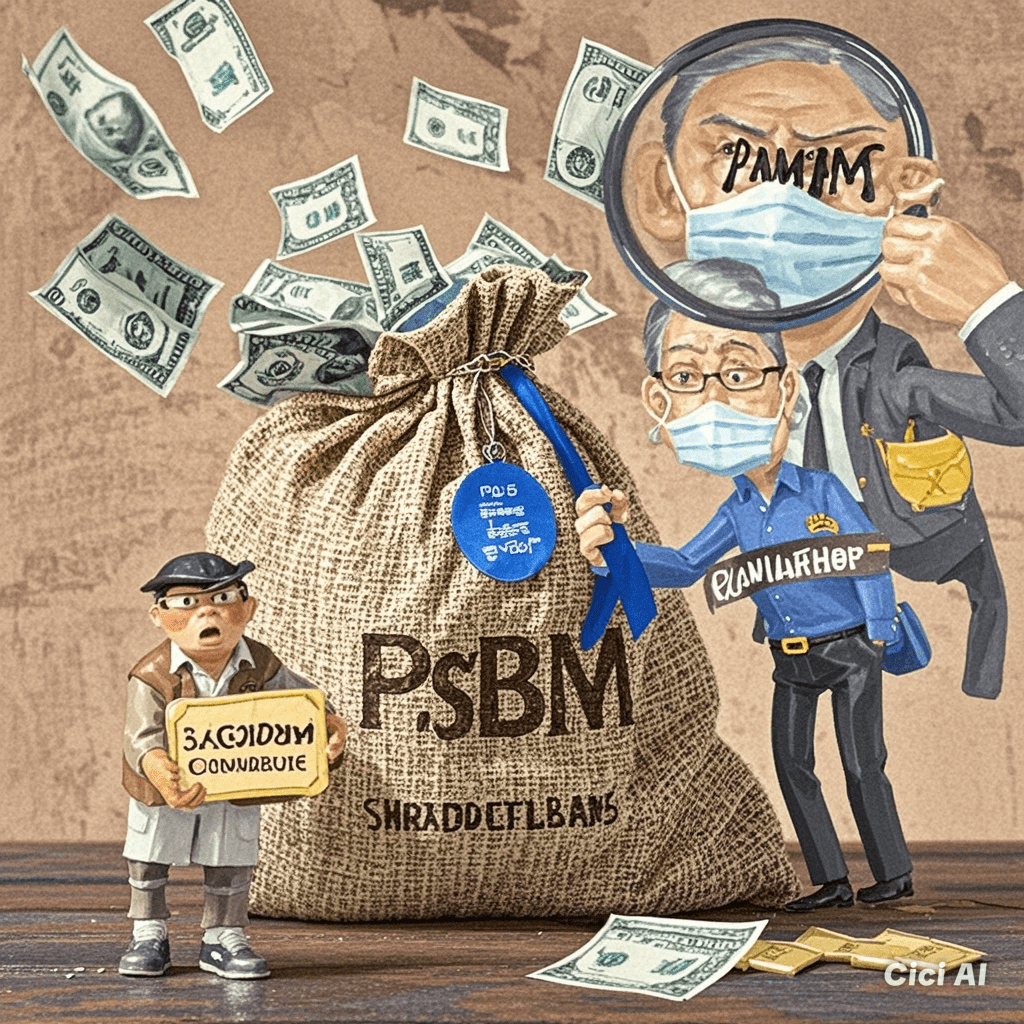

The Context of the Pharmally Scandal: An Empire of Corruption

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, as nations struggled to protect their citizens and economies, the Philippine government faced an unparalleled crisis. The procurement of vital medical supplies was not just a bureaucratic necessity but a matter of life and death. Yet, within this maelstrom of public health emergency, corruption allegedly found fertile ground.

Lao, as Officer-in-Charge of the PS-DBM, oversaw the disbursement of billions in government funds. The Ombudsman accuses him of accepting P41 billion from the Department of Health (DOH) without proper legal basis, charging a 4% service fee—approximately P1.65 billion—despite the DOH’s capacity to undertake the procurement. These funds were meant for the acquisition of medical equipment, from ventilators to personal protective equipment (PPE). Yet, the gravity of the Pharmally scandal extends beyond the mismanagement of billions. It’s about the alleged prioritization of profit over public welfare, with companies like Pharmally bagging contracts worth over P11 billion, despite their dubious qualifications.

Senator Gordon, as chairman of the Blue Ribbon Committee, has been the fiercest watchdog of this scandal. His relentless pursuit of the truth has peeled back layers of alleged graft, implicating high-ranking officials, including former President Rodrigo Duterte and his close confidantes. For Gordon, this case isn’t just about financial malfeasance. It’s about betrayal—leaders choosing self-enrichment while their countrymen gasped for air in overwhelmed hospitals.

The Legal Quagmire: Lao’s Arrest and the Ombudsman’s Case

At the center of the controversy are the legal entanglements that have now caught up to Lao. The Ombudsman has charged him under the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act (Republic Act 3019), a law designed to combat abuses by public officers. Lao’s acceptance of the P41 billion fund transfer, particularly with the addition of a service fee, is viewed as an act detrimental to the public interest. Furthermore, the Ombudsman contends that the transfer was unnecessary and in violation of the DOH’s own procurement capabilities.

However, Gordon argues that these charges, while significant, do not go far enough. His demand is clear: the accused should face charges of plunder, not mere graft. Under Philippine law, plunder (Republic Act No. 7080) applies to cases where a public officer amasses ill-gotten wealth of at least P50 million, and the penalties are much harsher—most notably, it is non-bailable. Gordon, citing the magnitude of the Pharmally scandal and the alleged conspiracy among Lao, Michael Yang, and others, insists that this threshold has been met.

His assertion rests not only on legal grounds but on the ethical standards enshrined in the Philippine Constitution and the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees (Republic Act 6713). These laws obligate public officials to act with integrity and fidelity to public service. In Gordon’s eyes, the actions of Lao and his alleged cohorts were not merely technical missteps—they were moral and legal betrayals.

The Power of Gordon’s Claims: Assessing the Evidence

Gordon’s unwavering stance has been rooted in a combination of legal precedent and public sentiment. He has pointed to the actions of other countries, particularly Vietnam, where senior officials were held accountable for COVID-19-related corruption. His argument for plunder charges draws from cases like Estrada vs. Sandiganbayan (2001), where the Philippine Supreme Court upheld the principle that when public officials conspire to misuse public funds, the charge of plunder is justified.

Yet, Gordon faces challenges. The burden of proving conspiracy at this level, particularly in the context of a pandemic where bureaucratic inefficiencies may be more easily conflated with corruption, is steep. The Sandiganbayan’s threshold for conviction will require incontrovertible evidence that Lao and others acted with deliberate malice and intent to defraud the government.

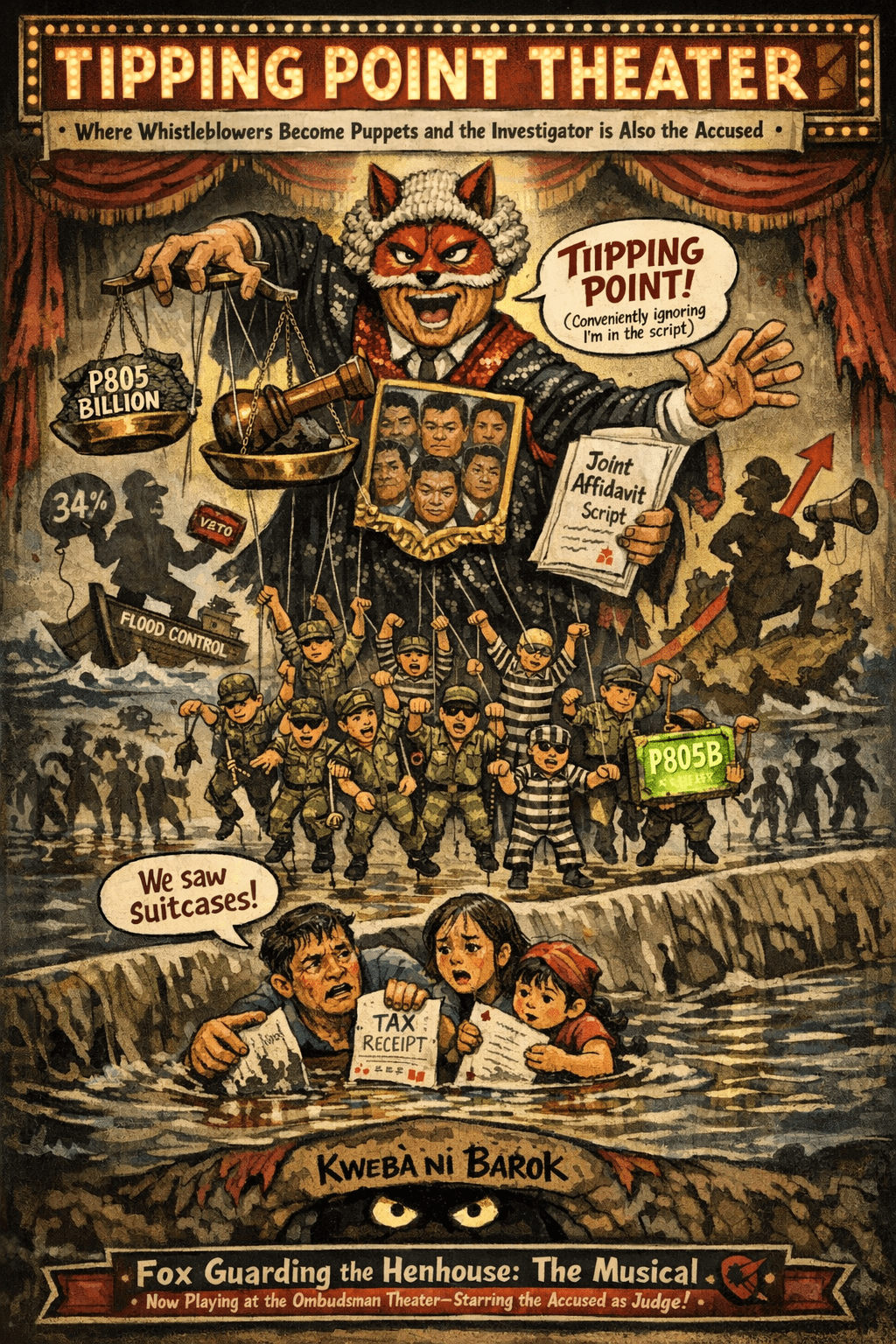

The Ombudsman’s Perspective: A Cautious Approach?

The Ombudsman’s filing of graft charges, rather than plunder, indicates a more cautious legal strategy. Graft, while serious, is easier to prove and more within the realm of administrative failures, something that Lao’s legal team will likely exploit in their defense. The Ombudsman will argue that Lao’s acceptance of the P41 billion was an abuse of his position, but whether this amounts to plunder remains legally contentious. Philippine Supreme Court cases such as Garcia vs. Sandiganbayan (2008) have shown that proving plunder requires clear and convincing evidence of amassing ill-gotten wealth, beyond simple malfeasance.

Legal Options for Gordon

Gordon has a range of legal options. He can continue pushing for plunder charges, seeking to elevate the case from one of bureaucratic corruption to a full-scale conspiracy. He could also file further complaints with the Ombudsman, using the Blue Ribbon Committee’s findings as additional evidence. If dissatisfied with the Sandiganbayan’s handling of the case, Gordon could seek to appeal or pursue civil actions aimed at recovering the misused funds.

Recommendations

For Senator Gordon, his strongest course of action may lie in building a coalition within the Senate and public advocacy groups to apply pressure for a more aggressive legal stance. By rallying public opinion and utilizing the media to highlight the severity of the scandal, he can push for greater accountability.

The Ombudsman, meanwhile, should consider the broader implications of this case. While graft charges may seem like the most pragmatic option, the public’s demand for justice in such a significant case of corruption during a national crisis cannot be ignored. Reevaluating the possibility of plunder charges may be necessary, especially if new evidence emerges.

Conclusion: A Nation Awaits Justice

As Lao’s fate remains uncertain, the real trial begins—not just in the courtroom, but in the court of public trust. This is not merely about one man, but about a system that has for too long allowed corruption to thrive unchecked. The Filipino people stand at a crossroads: will the Ombudsman’s pursuit of justice be enough, or will Senator Gordon’s call for plunder charges rewrite the rules of accountability? The answer will define not just this case, but the very fabric of trust in our institutions.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

Leave a comment