By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — October 24, 2024

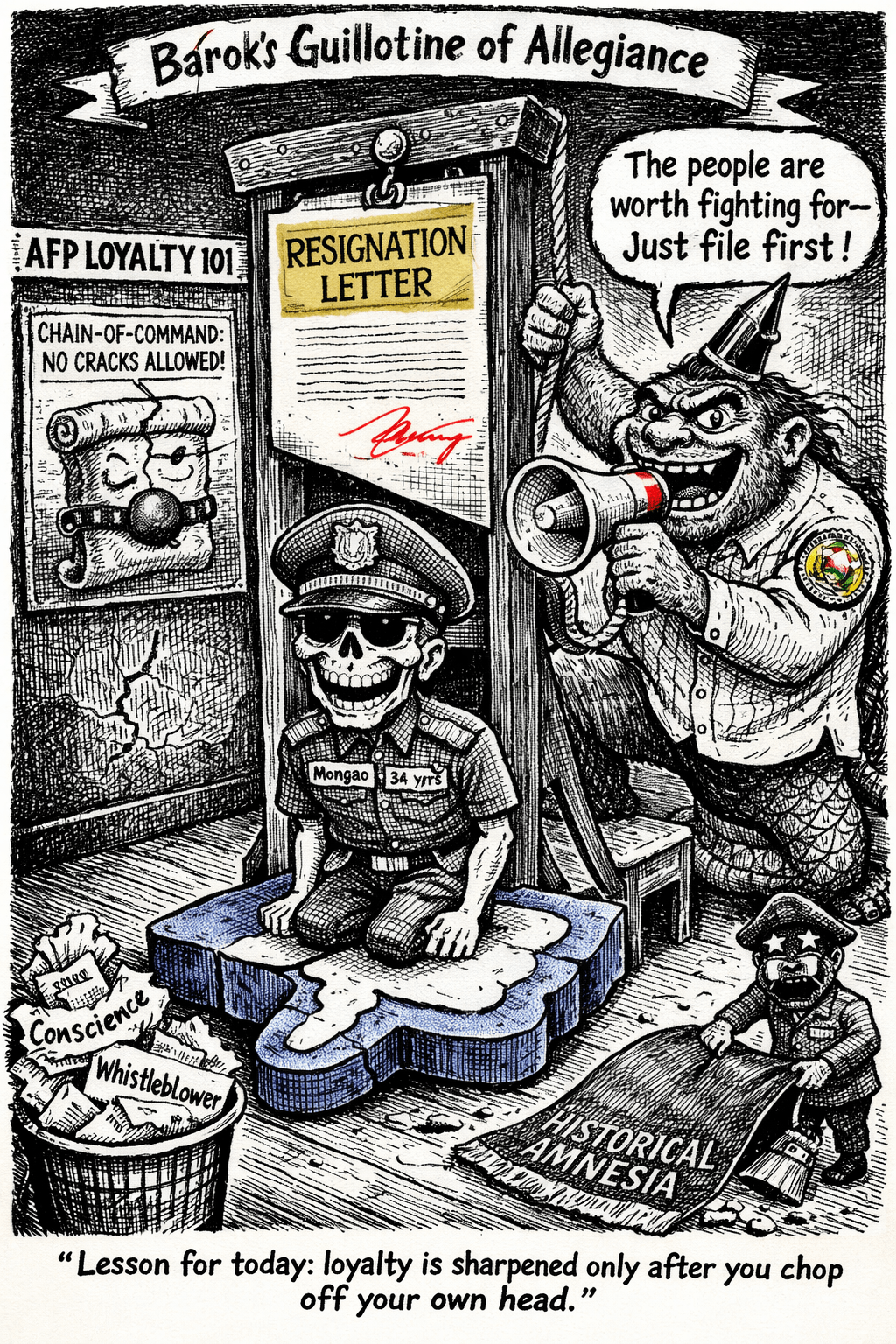

THE man who once wielded unchecked power over the Philippines may soon find himself ensnared by his own country’s laws. Rodrigo Duterte, the former president who built a legacy on tough talk and harsher actions, now faces the surprising threat of Republic Act No. 9851—a law so obscure it barely registered in the public consciousness until now. But in a twist of fate, it’s Leila De Lima, the very woman Duterte once tried to destroy, who is leading the legal offensive that could deliver him into the hands of the International Criminal Court.

The Duterte-De Lima Feud: Years of Bad Blood

The animosity between Duterte and De Lima began long before the former ascended to the presidency. In 2009, when De Lima served as Chair of the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), she opened an investigation into the Davao Death Squad, a vigilante group believed to be linked to Duterte during his time as mayor of Davao City. The CHR uncovered shocking details, including accounts that Duterte himself orchestrated extrajudicial killings. For Duterte, De Lima became a relentless adversary. She was, in his eyes, a threat—a woman who not only sought to reveal the dark side of his leadership but also to dismantle the moral justification he had built around his ruthless approach to law and order.

By the time Duterte was president, he made it his mission to neutralize De Lima. In 2017, under his administration, De Lima was arrested on drug charges that many believe were politically motivated. Yet despite her years of imprisonment, she has not been silenced. Instead, De Lima has seized on an unexpected weapon: RA 9851.

RA 9851: A Legal Loophole or the Sword of Justice?

Republic Act No. 9851, enacted in 2009, could become Duterte’s undoing. The law defines and penalizes crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide, and it contains a crucial provision: Section 17 allows the Philippines to cede its authority to prosecute such crimes if an international tribunal—like the ICC—is already investigating. De Lima has spotlighted this provision in her testimony, asserting that even though the Philippines withdrew from the Rome Statute in 2019, the ICC retains jurisdiction over Duterte’s alleged crimes because they were committed when the country was still a signatory.

This argument hinges on RA 9851’s unique legal construction. Although it predates the Philippines’ membership in the ICC, the law still recognizes the ICC’s jurisdiction over crimes committed in the country. In other words, the Philippines cannot claim sovereignty as a shield if it has already legislated to allow international courts to step in when domestic authorities fail to act.

De Lima’s Legal Expertise and the RA 9851 Gambit

De Lima’s legal prowess is formidable. She is not just a former senator but also a seasoned lawyer and a former justice secretary. She has an intimate understanding of the law and how it can be wielded to deliver justice. By invoking RA 9851, De Lima aims to sidestep the political games that Duterte’s supporters have played in trying to shield him from accountability.

Her reading of the law is astute. The language of Section 17 could compel the Philippine government to cooperate with the ICC, as it acknowledges that the state cannot absolve itself from investigating crimes against humanity by merely ignoring them. Furthermore, the law’s provision allowing extradition or surrender of suspects to international courts is a significant legal anchor, one that directly challenges Duterte’s claim to immunity after the Philippines’ withdrawal from the Rome Statute.

Counter-Arguments and the Complexity of Sovereignty

Yet Duterte’s camp is not without counter-arguments. His defenders will likely argue that the Philippines’ withdrawal from the ICC nullifies any ongoing investigations or obligations, invoking the principle of sovereign immunity. They might also claim that RA 9851 cannot retroactively bind the Philippines to an international court if the country has since renounced its participation in that court’s system.

This argument, while legally plausible, faces challenges. First, there is the question of timing: the alleged crimes occurred when the Philippines was still a member of the ICC. More importantly, international law often holds that withdrawal from a treaty does not absolve a state of responsibility for acts committed while it was still party to the agreement. The ICC itself maintains that it can continue its investigation, which complicates Duterte’s defense. Nevertheless, his legal team could challenge this interpretation in the Supreme Court, leveraging Philippine precedents to argue for a narrow reading of RA 9851 that prioritizes national sovereignty over international obligations.

The Philippine Government’s Potential Stance

The Philippine government, under the current administration, finds itself in a precarious position. Public opinion on Duterte remains divided, and acceding to De Lima’s interpretation of RA 9851 could have political costs. The government could argue that the law’s language is discretionary, not obligatory, meaning that Philippine authorities retain the right to decide whether to hand Duterte over to the ICC.

Furthermore, the government could invoke principles of necessity and fairness, asserting that the ICC’s intervention undermines the sovereignty of the Philippines’ judicial system. This would be a delicate balancing act: upholding the rule of law while navigating the political minefield of Duterte’s lingering influence.

Legal and Political Ramifications

If the government accedes to De Lima’s assertions and allows Duterte to be tried by the ICC, the consequences could be far-reaching. Domestically, it would signal a commitment to human rights and international law, but it could also trigger political instability. Duterte’s supporters, still a formidable force, might perceive this as a betrayal and rally against the current administration. Internationally, it would restore the Philippines’ credibility in the global community after years of strained relations with human rights organizations.

Should the government refuse, it risks being seen as complicit in shielding a former leader from accountability. This could sour relations with the international community and embolden the ICC to pursue alternative methods, such as issuing an arrest warrant that could be executed in a third-party state.

Recommendations

For De Lima, the path forward is clear: continue to use RA 9851 as a legal linchpin to press for accountability. For Duterte, the stakes could not be higher. His best defense may be to confront the allegations head-on, though doing so in an ICC trial would expose him to international scrutiny.

The Philippine government should carefully weigh its options. Upholding RA 9851 would demonstrate its commitment to human rights, but it must be prepared for the political fallout. Finally, the ICC must remain steadfast in its pursuit of justice, undeterred by political maneuvering.

Duterte’s war on drugs has left a scar on the nation, but scars tell stories. The next chapter isn’t about erasing the past—it’s about ensuring that the wounds left behind heal with justice and dignity. And in this battle, the final verdict still belongs to the people.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

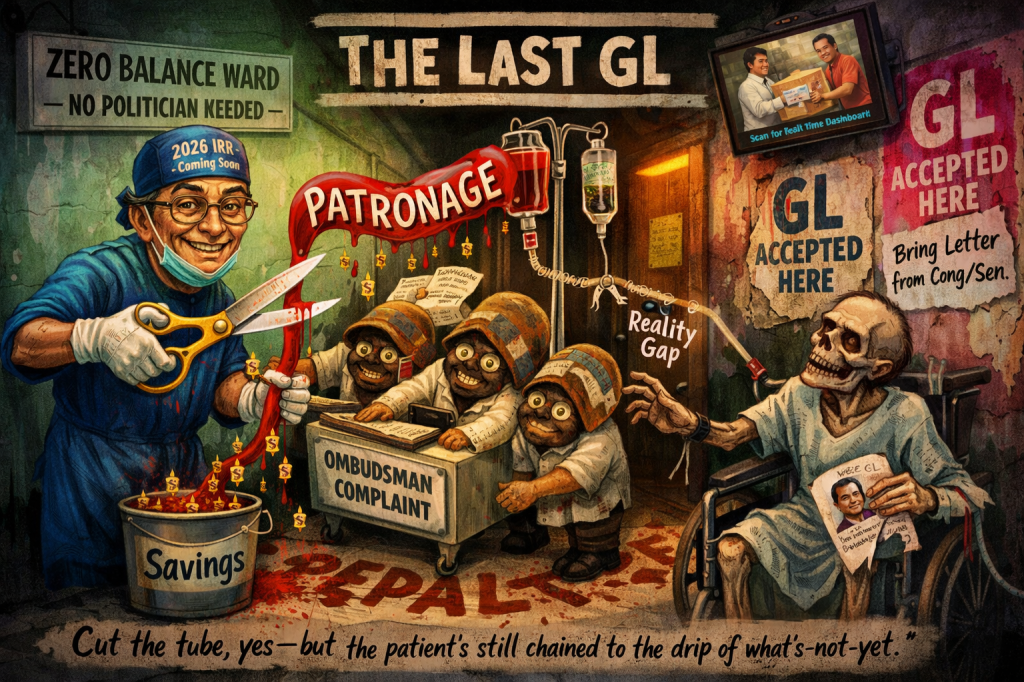

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

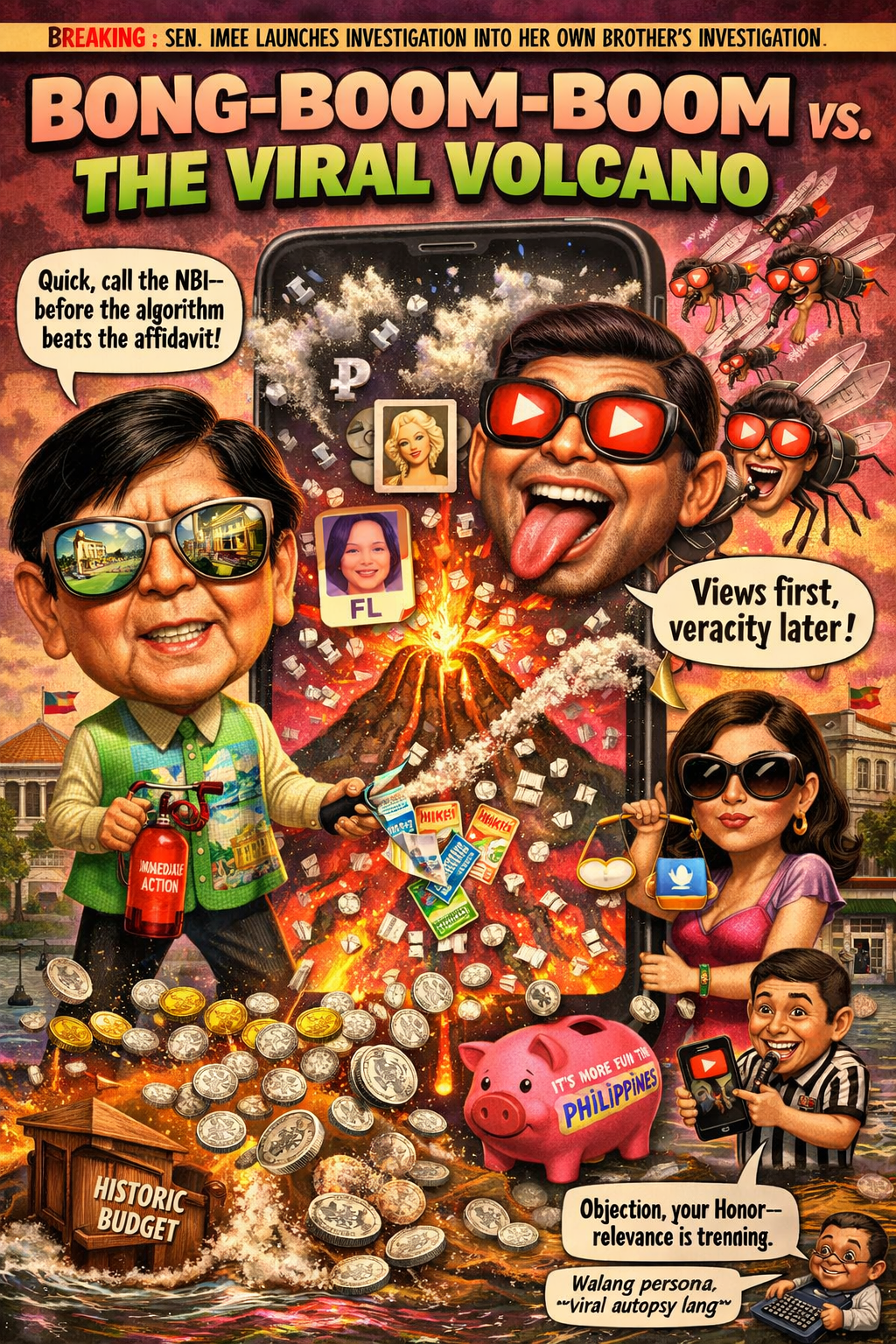

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

- “Allocables”: The New Face of Pork, Thicker Than a Politician’s Hide

- “Ako ’To, Ading—Pass the Shabu and the DNA Kit”

Leave a comment