By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — December 2, 2024

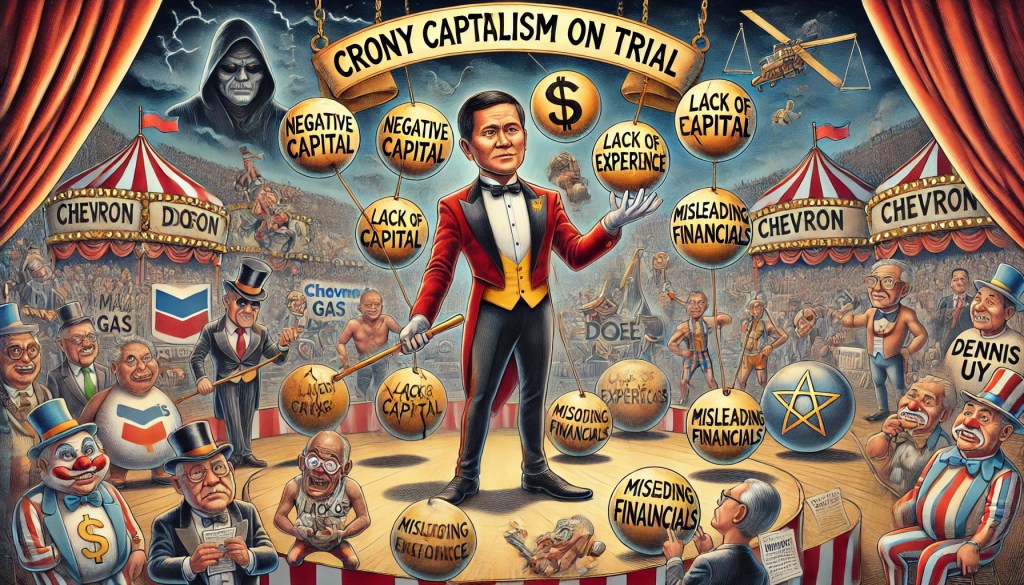

THE Malampaya gas project: a lifeline for energy—or a lightning rod for corruption? Allegations of graft surrounding Dennis Uy’s acquisition of Chevron’s stake have drawn sharp focus to former Energy Secretary Alfonso Cusi and 11 DOE officials. As the Ombudsman’s findings ignite a legal and political firestorm, this piece unpacks the charges, defenses, and implications of one of the year’s most contentious cases.

The Controversy in Context: A Closer Look

In 2019, Dennis Uy, through his company Udenna Corp., purchased 45 percent stake Chevron’s stake in the Malampaya gas project for $565 million, a deal that has been controversial for several reasons. The Ombudsman has found probable cause that Cusi and other DOE officials violated Republic Act No. 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act) by pushing the deal despite glaring red flags. These include Udenna’s negative capital, lack of technical expertise, and the use of misleading financial evaluations to present Udenna as a qualified buyer. The Ombudsman’s findings are significant, as they could lead to criminal charges and removal from office for the implicated officials.

The question at the heart of this scandal is whether public officials acted in bad faith, as accused by the Ombudsman, or whether they were merely exercising discretion in a complex and high-stakes transaction.

The Legal Merits of the Ombudsman’s Position

The Ombudsman’s findings center on the violation of Section 3(e) of the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act (Republic Act No. 3019), which prohibits public officials from showing bias, bad faith, or negligence that results in undue favor to a private party. This provision is central to the Ombudsman’s case, as the officials allegedly allowed a transaction to proceed despite several issues with Udenna’s qualifications.

- Section 3(e) of the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act: The core legal argument for the Ombudsman’s case is that Cusi and his co-respondents abused their power to benefit Dennis Uy. The law criminalizes acts where officials act in bad faith, bias, or negligence when favoring a private party. If these officials ignored Udenna’s financial instability, lack of technical expertise, and misrepresentation of their financial capacity, they would likely have violated this provision. Case law (e.g., People v. Benedicto, G.R. No. 127976, February 15, 2000) supports the premise that even negligent acts resulting in substantial harm to public interests may be penalized under this provision.

- Conflict of Interest and the Public Trust: The involvement of Dennis Uy, a known ally of former President Duterte, raises concerns of conflict of interest and favoritism. The Supreme Court has consistently emphasized that public officials must act in the public interest and avoid any actions that might betray the trust reposed in them by the people. In Salazar v. Ombudsman (G.R. No. 178922, January 18, 2016), the Court noted that the public trust must not be compromised by the personal interests of government officials.

- Unqualified Buyer and Misleading Financials: The allegations of Udenna being an unqualified buyer due to negative capital and lack of technical expertise are serious. According to the Securities Regulation Code (Republic Act No. 8799), companies must meet certain financial and technical requirements to engage in such high-stakes transactions. Ignoring such requirements would constitute a violation of the law, especially if done in a manner that favors a private individual or corporation at the expense of public interests.

A Legal Defense Toolkit: Strategies to Counter the Ombudsman’s Assertions

From a legal standpoint, there are several potential counter-arguments that Cusi and the DOE officials could raise in their defense.

- Discretion in Decision-Making: One possible defense is that the DOE officials exercised their discretion within the bounds of their authority. In Bacolod City Water District v. CA (G.R. No. 127657, July 15, 2002), the Supreme Court ruled that public officials have broad discretion in decision-making as long as they act within the law. The respondents might argue that the transaction was within their powers and that they were not obligated to investigate the financials of Udenna more deeply.

- Lack of Malice or Bad Faith: Another defense would be that the officials did not act in bad faith, but instead made a judgment based on the information available at the time. In Guevara v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 105431, March 29, 1994), the Court clarified that the mere presence of bad results does not automatically imply bad faith unless clear evidence shows intentional wrongdoing.

- No Causal Link to Harm: Defendants may argue that there is no clear evidence linking their actions to any specific harm to the public interest or financial losses. They might claim that even though Udenna’s financials were problematic, the deal still went through in accordance with lawful procedures and did not result in any direct harm.

A Balanced Perspective

While the Ombudsman’s case appears strong in terms of the statutory violations, the counter-arguments are not without merit. The defense could potentially argue that the decisions made were within the bounds of the officials’ authority and did not rise to the level of corruption or bad faith. However, the glaring issues with Udenna’s qualifications, the potential conflict of interest given Dennis Uy’s ties to the Duterte administration, and the apparent use of misleading financial evaluations strongly tilt the balance in favor of the Ombudsman’s findings.

Recommendations

- For Dennis Uy: Given the serious nature of the allegations, Uy should seek to distance himself from the controversial aspects of the transaction. It may be beneficial for him to cooperate with authorities and address any issues of misrepresentation in the deal, as transparency could mitigate potential legal and reputational damage.

- For Cusi and the Implicated DOE Officials: The implicated officials should prepare for a rigorous legal defense, particularly focusing on proving that their actions were in good faith and within the scope of their official duties. However, they should also be prepared for potential consequences if the Ombudsman’s findings hold.

- For the Ombudsman: The Ombudsman must ensure that the investigation remains transparent and free from political influence. Given the public’s distrust of political corruption, a fair and thorough investigation is necessary to uphold the integrity of public office.

- For the Filipino People: This case underscores the need for stronger safeguards against corruption, particularly in high-stakes government transactions. Public trust is paramount, and it is critical that the government adopt more stringent measures to prevent undue influence from private interests in state-controlled assets. More stringent regulatory oversight, especially in the energy sector, would go a long way toward restoring public confidence.

This case isn’t just about laws and frameworks—it’s about trust in institutions and the enduring fight for a government that serves its people. While the Ombudsman’s findings bring us closer to the truth, the complexity of the case reminds us that justice demands persistence. Let this be a turning point, not just for Malampaya, but for the integrity of our nation.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

- $2 Trillion by 2050? Manila’s Economic Fantasy Flimsier Than a Taho Cup

- $26 Short of Glory: The Philippines’ Economic Hunger Games Flop

Leave a comment