By Louis ‘Barok‘ C Biraogo — December 19, 2024

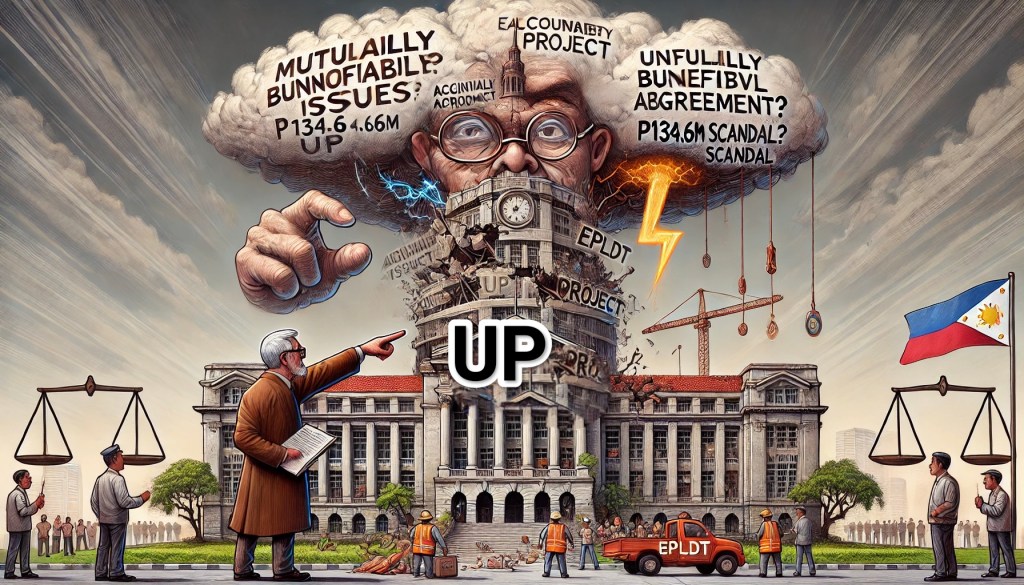

THE P134.6-million eUP Project was meant to modernize the University of the Philippines (UP), but instead, it has become the epicenter of a brewing scandal. In its scathing 2023 report, the Commission on Audit (COA) exposes troubling lapses in UP’s governance, raising questions about whether the country’s flagship university has lived up to its legal and ethical responsibilities—or has quietly betrayed the public trust it holds so dearly.

The Core Issue: Failure to Enforce Accountability

COA’s report underscores a glaring failure by UP to hold its contractor, ePLDT, accountable for almost six years of delays in completing the eUP Project. The university neither collected the P39.7 million in liquidated damages nor pursued the blacklisting of ePLDT from future government projects. Despite a clear mandate under procurement laws and COA’s 2022 recommendations, UP’s enforcement actions were limited to drafting internal memos without concrete follow-through.

This inaction is exacerbated by ePLDT’s public statement about a “mutually beneficial agreement in principle” with UP to resolve the matter—an arrangement shrouded in ambiguity and devoid of public scrutiny. Has UP prioritized expediency over compliance, and at what cost to public accountability?

Legal Obligations and the Role of COA

Under the Revised Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR) of Republic Act No. 9184 (Government Procurement Reform Act), public entities like UP must impose liquidated damages for delayed projects and, when warranted, blacklist erring contractors. Liquidated damages, calculated as a percentage of the total contract price per day of delay, are non-negotiable unless explicitly waived under clear legal grounds. Further, blacklisting provisions ensure accountability and prevent habitual delinquency in public contracts. COA, tasked with auditing and enforcing these safeguards, has the legal standing to demand compliance.

If UP failed to deduct liquidated damages from payments due to ePLDT or claim from the performance bond as COA suggested, it may have violated these procedural safeguards. Additionally, by not initiating blacklisting procedures, UP arguably disregarded its duty to protect public interest, setting a dangerous precedent for future government projects.

UP’s Defense: Examining the Arguments Against the COA’s Assertions

On the other hand, UP might argue that its unique institutional status as a state university confers certain discretionary powers. As a government agency with fiscal and administrative autonomy under the UP Charter of 2008 (Republic Act No. 9500), UP could assert that decisions regarding contract enforcement fall within its internal prerogatives. The purported “mutually beneficial agreement” with ePLDT might reflect an effort to preserve institutional relationships, especially if the contractor remains integral to the project’s eventual success.

Moreover, UP may invoke the principle of amicable settlement under the Alternative Dispute Resolution Act of 2004 (Republic Act No. 9285) to justify its decision to resolve disputes outside the courts or administrative channels. However, any such settlement must be transparent, lawful, and in the public’s best interest—a standard UP’s agreement with ePLDT has yet to meet.

Broader Implications for UP and Public Accountability

If COA’s assertions are upheld, the potential fallout for UP is significant. Financially, it may face legal liabilities for failing to enforce penalties, recover public funds, or secure undelivered services. Administratively, its leadership could be subjected to investigations for negligence under Republic Act No. 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act). The university’s credibility as a steward of public resources and a bastion of academic integrity would also suffer, undermining its capacity to attract partnerships and funding.

Conversely, a failure to enforce COA’s findings risks setting a dangerous precedent, where institutional autonomy becomes a shield for inaction. Public trust in COA’s authority, already tenuous, could erode further, emboldening contractors to flout government regulations with impunity.

The Role of Media and Public Perception

The media’s portrayal of the controversy will inevitably shape public opinion. Reports highlighting UP’s apparent failure to enforce accountability could frame the institution as complicit in mismanagement, tarnishing its reputation. Yet, narratives emphasizing UP’s efforts to negotiate a settlement might sway public sentiment toward seeing the university as pragmatic rather than negligent. In either case, the controversy risks becoming a litmus test for the public sector’s commitment to good governance.

Conclusion: A Crossroads for Accountability

UP stands at a crossroads, its actions in this case carrying implications far beyond the eUP Project. Will it assert its autonomy responsibly, or will it succumb to a culture of impunity? COA’s findings demand answers—not only from UP but also from the broader system of accountability that governs public institutions. For UP to truly fulfill its mandate as the nation’s premier university, it must lead by example, demonstrating that integrity and transparency are non-negotiable in the pursuit of public service.

The coming months will reveal whether UP can rise to this challenge—or whether it will be remembered as an institution that allowed accountability to slip through its hands, much like the undelivered promises of the eUP Project.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment