By Louis ‘Barok’ C Biraogo — February 22, 2025

IN A Manila slum where families scrape by on a few hundred pesos a day, a political party supposedly representing the urban poor boasts a nominee who owns two construction companies, a mining concession, and government contracts worth millions. If that sounds absurd, it’s because it is. This is the state of the Philippines’ party-list system—originally designed to amplify the voices of the marginalized but now a playground for the powerful.

The Original Intent and Its Subversion

The party-list system was enshrined in the 1987 Philippine Constitution with noble intentions: to ensure that underrepresented sectors—peasants, fisherfolk, laborers, indigenous peoples—had a seat at the table. Republic Act 7941, the Party-List System Act, was meant to provide a counterbalance to the dominance of political dynasties and entrenched elites.

But instead of empowering the powerless, the system has been captured by those who already wield economic and political influence. A 2025 study by the election watchdog Kontra Daya found that over 55% of party-list groups were controlled by political dynasties, business magnates, or government officials. The latest scandal—a party-list led by the wife of a Commissioner on Audit (COA), with nominees deeply embedded in construction, mining, and government contracting—exemplifies the brazen exploitation of the system.

A System Ripe for Conflicts of Interest

Consider the case of the first nominee of this anonymous party-list. As the wife of a COA commissioner, she has direct ties to an agency tasked with auditing government spending. Yet her construction firms have secured multimillion-peso contracts from the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) and the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA), while her mining company enjoys a vast concession granted by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). This is a textbook case of conflict of interest—COA must scrutinize the very agencies awarding contracts to its commissioner’s spouse.

The third nominee, another businesswoman, is the wife of a construction magnate whose firm has DPWH contracts and MMDA garbage collection deals. Notably, COA had previously flagged her company for financial irregularities, but the ruling was overturned on appeal by none other than the COA commissioner-husband of the first nominee.

The Napoles Connection: Political Legacies of Corruption

Then there’s Kaunlad Pinoy, another so-called representative of the marginalized. Its first nominee? James Christopher Napoles, son of Janet Lim-Napoles—the mastermind behind the infamous pork barrel scam that siphoned billions from public funds. Though Napoles herself is serving a life sentence for plunder, her family remains entrenched in Philippine politics. Her son, despite facing nearly a hundred counts of graft and malversation, is seeking a congressional seat under the guise of advocating for small businesses.

That such figures can exploit the party-list system reveals its profound vulnerabilities. If a mechanism meant to uplift the underprivileged can be co-opted by political families and business tycoons, what hope remains for genuine grassroots organizations?

The Role of Oversight Bodies: Enablers or Watchdogs?

The Commission on Elections (Comelec) and COA are supposed to be the gatekeepers of electoral integrity, yet both have failed spectacularly. Comelec disqualifies nuisance candidates for frivolous reasons but allows party-lists with clear ties to political dynasties and big business to run unchecked. In 2025, Kontra Daya flagged 86 of 156 party-list groups as questionable—yet Comelec failed to act decisively.

COA, meanwhile, is compromised from within. When an official’s spouse and close associates benefit from government contracts while the agency ostensibly overseeing public expenditures looks the other way, the integrity of the entire system collapses.

Patterns of Exploitation Across Elections

The manipulation of the party-list system is not new. In the 2019 elections, 46.3% of party-list groups had links to political dynasties or big business. By 2022, the figure had climbed to 67.8%. Instead of serving as an equalizing force, the party-list system has become a backdoor for traditional politicians and economic elites to consolidate power.

This trend is alarming because it dilutes the representation of genuinely marginalized sectors. Farmers, indigenous peoples, and urban poor communities—those who should be benefiting from the system—are increasingly edged out by groups with deeper pockets and stronger political ties.

The Future of Philippine Democracy: A Question Mark

At its core, this corruption of the party-list system is an attack on democratic representation. When the wealthy and powerful manipulate mechanisms meant for the underprivileged, it reinforces the deeply entrenched inequalities in Philippine society. It also undermines public trust in democratic institutions. If voters perceive the electoral system as rigged in favor of elites, disengagement and political apathy will follow, making genuine reform even harder to achieve.

This problem extends beyond the Philippines. Around the world, systems designed to increase representation—from India’s caste-based reservations to the United States’ campaign finance reforms—are often hijacked by those they were meant to check. But there are successful models of reform.

Lessons from Other Countries: Paths to Reform

Germany’s mixed-member proportional representation system provides one potential blueprint. There, party-list seats are allocated based on a strict proportional representation model, with stringent requirements to ensure broad-based public support. South Africa’s system, while also proportional, includes measures to prevent corporate capture of party-list representation.

The Philippines could adopt similar safeguards:

- Stricter Qualification Standards – Party-list nominees should be required to demonstrate direct involvement in the sectors they claim to represent. This means clear documentation of grassroots work, financial independence from big business, and a ban on political dynasty members.

- Enhanced Comelec Oversight – An independent vetting body, composed of civil society groups, legal experts, and election watchdogs, should scrutinize party-list applicants before they are accredited.

- Transparency in Funding and Membership – Party-lists should be required to disclose funding sources and membership demographics to ensure genuine representation.

- Stronger Anti-Conflict-of-Interest Rules – Public officials and their immediate family members should be barred from holding positions in party-lists that engage in government contracting.

- Automatic Disqualification for Corruption-Linked Figures – Individuals with pending graft and corruption cases should be barred from running under the party-list system.

It’s Time to Stand Up: A Call to Action

The party-list system, at its best, is a tool for empowerment. But in its current state, it is a mechanism for elite entrenchment. If the Philippine government is serious about electoral reform, it must close the loopholes that allow political dynasties and business elites to hijack representation.

Voters, too, must be vigilant. As election season approaches, the electorate must scrutinize party-list candidates with the same rigor as those running for traditional legislative seats. Civil society organizations, journalists, and watchdogs must continue exposing the abuses within the system.

When the champions of the oppressed are, in reality, the oppressors themselves, the essence of representation is lost. The Philippines stands at a pivotal moment: will it allow the powerful to continue their masquerade, or will it reclaim the party-list system for those whose voices have been silenced for too long?

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

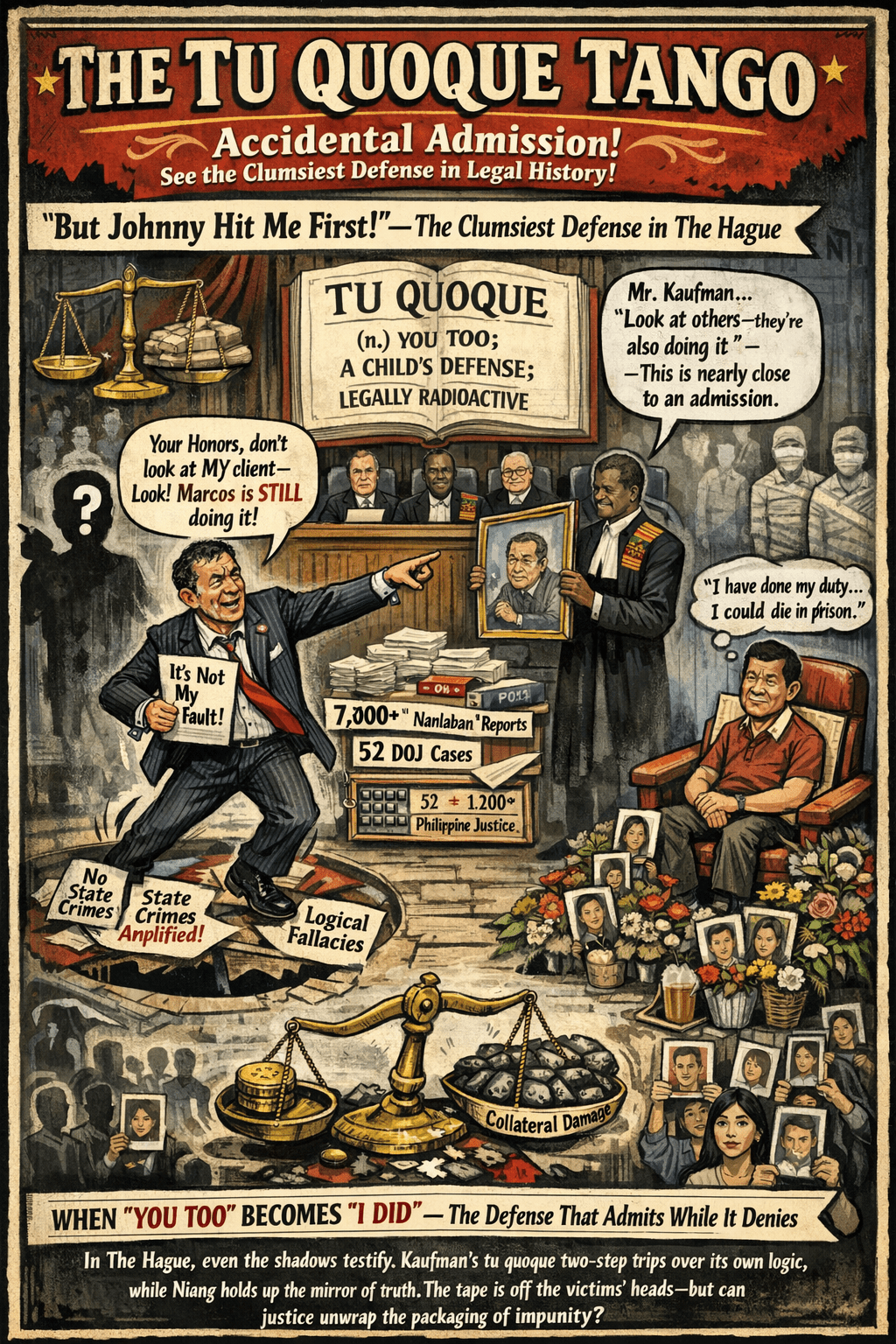

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment