By Louis ‘Barok’ C Biraogo — February 23, 2025

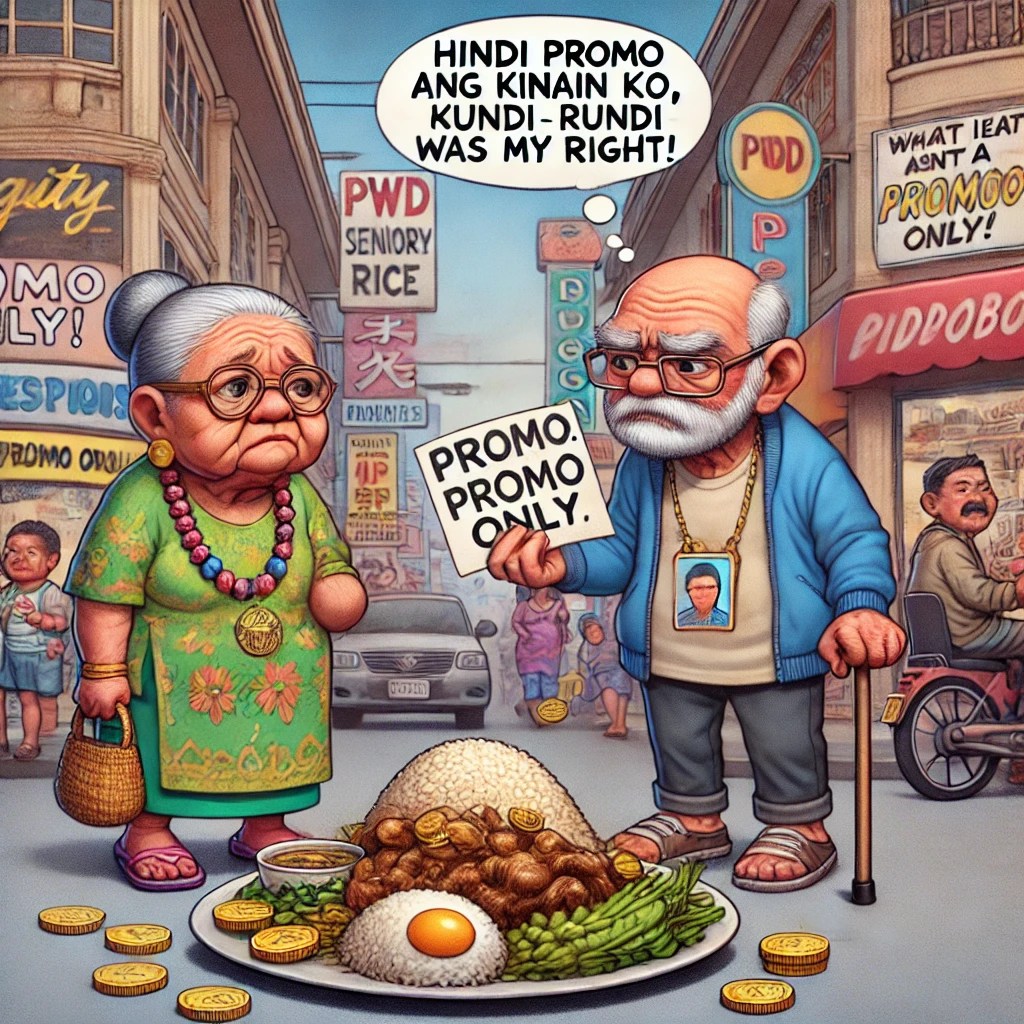

THE adobo at her favorite Quezon City restaurant usually tasted like comfort and a small victory for 72-year-old Lola Elena. Today, it tasted like disappointment. Her senior citizen discount, a right under Philippine law (Republic Act 9994 and Republic Act 10754), had been denied, swallowed by a confusing “promo.” As Lola Elena left, her worn ID card felt heavier than ever, a symbol of a right lost in the fine print.

Across town, there’s Mang Tony, a jeepney driver with a limp from a childhood accident, proudly carrying his PWD ID. He stops at a hotel diner, expecting the same 20 percent off and VAT exemption he’s legally guaranteed. Instead, he’s met with a curt, “Promo lang po ito,” and a bill that stings more than it should. These aren’t isolated stories—they’re threads in a troubling tapestry of unauthorized business promotions quietly eroding the rights of the Philippines’ most vulnerable citizens.

The Phantom Discount: How the Elderly Lost Twice

This isn’t just about a few pesos skimped on a meal. It’s a systemic failure that pits profit against dignity. The Consumer Act of the Philippines (Republic Act 7394) is clear: under Article 116, any sales promotion campaign requires a permit from the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), applied for at least 30 days in advance. The intent is to protect consumers—especially seniors and PWDs—from deceptive practices. Yet, as Atty. Romulo Macalintal pointed out in a fiery statement on February 21, 2025, some restaurants and hotels flout this rule, slapping “promo” labels on regular prices to dodge the discounts mandated by law. It’s a clever loophole, but it’s exploitation dressed up as marketing.

The numbers tell a stark story. The Philippine Statistics Authority pegged the senior population at 9.22 million in 2020, while over 1.9 million Filipinos live with disabilities, per estimates tied to RA 10754. These groups rely on their discounts not as handouts, but as rights—small buffers against rising costs and fixed incomes. When businesses sidestep these protections, they don’t just cheat the system; they rob Lola Elena and Mang Tony of agency and respect.

When Compliance Becomes Camouflage

Take the case of a Manila hotel chain recently called out on social media. A “weekend promo” slashed room rates by 15 percent—no DTI permit in sight. When a PWD guest demanded her 20 percent discount, the manager shrugged: “Promo price na po.” Legally, without that permit, the “promo” is a fiction; the regular price should apply, and the discount should kick in. But enforcement is patchy, and awareness is low. The hotel walks away richer, the guest poorer—and the law sits idly by.

Restaurants pull similar stunts. A viral post from Restaurant Owners of the Philippines (Resto PH) bemoaned fake PWD cards draining profits—an issue worth tackling. But Macalintal flipped the script: what about fake promos? A diner in Makati advertised a “buy one, get one” deal, yet refused seniors their discount, claiming the offer was exclusive. No permit, no transparency—just a dodge. These aren’t promotions; they’re sleights of hand, exploiting the trust of those least equipped to fight back.

Written in Law, Lost in Practice

Philippine law isn’t toothless. RA 7394’s Consumer Act aims to shield against “deceptive, unfair and unconscionable sales acts” (Article 2), with fines up to ₱5,000 or jail time for first-time offenders under Article 122. RA 10754 and RA 9994 grant seniors and PWDs their 20 percent discount and VAT exemption on goods and services—hotels, restaurants, medicines, transport—explicitly for their “exclusive use and enjoyment.” Businesses can even claim these discounts as tax deductions under Section 8(d) of RA 10754, softening the financial blow. Yet the loophole lies in enforcement: without rigorous DTI oversight, “promo” becomes a magic word to evade accountability.

Tax implications add another layer. Establishments deduct discounts from gross income, per the National Internal Revenue Code, but only if documented properly. Unauthorized promos muddy this process, potentially inflating profits while shortchanging the vulnerable. Compliance is a maze—small businesses groan under the red tape, while bigger players exploit the chaos.

Voices in the Tug-of-War

For seniors and PWDs, it’s personal. “I feel cheated,” Lola Elena told me, her voice trembling not with age but indignation. “This discount is all I have to stretch my pension.” Mang Tony echoed her: “They see my cane and think I won’t argue.” The emotional toll compounds the financial hit—dignity erodes with every denial.

Business owners see a different angle. Resto PH’s complaint about fake PWD cards isn’t baseless—fraud costs them, too. A small eatery owner in Cebu admitted to me, “We’re barely breaking even. Every discount hurts.” But when pressed on unauthorized promos, he grew quiet. Larger chains, meanwhile, lean on scale: a 20 percent hit across hundreds of transactions stings less than it does a mom-and-pop shop. Still, the law offers relief—those tax deductions could ease the burden if only compliance were simpler.

Regulators, chiefly the DTI, face a Herculean task. Understaffed and overstretched, they struggle to monitor a sprawling retail landscape. “We need more boots on the ground,” a DTI insider confided, requesting anonymity. Local government units (LGUs), tasked with field complaints via Persons with Disability Affairs Offices, are equally strained. Enforcement lags, and the vulnerable pay the price.

Beyond Band-Aids: Engineering Real Change

This isn’t insoluble—it’s a call to action. First, tighten the law. Amend RA 7394 to explicitly classify unauthorized promos as “deceptive practices,” with steeper penalties—say, ₱50,000 fines and mandatory refunds—to deter offenders. Cross-reference with RA 10754 and RA 9994 to ensure discounts apply regardless of promotional claims unless DTI-approved.

Second, bolster enforcement. Fund DTI and LGU task forces to spot-check promos, leveraging tech—think a public app to report violations in real time. Tie permits to a streamlined online portal, cutting red tape while tracking compliance. Make disciplinary actions public; shame is a powerful motivator.

Third, simplify business compliance. Expand tax deduction awareness campaigns—many owners don’t know they can offset discounts. Offer small firms amnesty to register past promos, paired with training on legal obligations. Balance the carrot and stick.

Finally, empower consumers. Launch a nationwide “Know Your Rights” drive—billboards, radio spots, barangay workshops—teaching seniors and PWDs to demand receipts and report denials. Partner with advocacy groups like Macalintal’s to amplify their voice.

Standing With Our Elders: The Path to Justice

What Lola Elena and Mang Tony seek isn’t charity—it’s dignity. The Philippines prides itself on robust laws, yet too often they exist only in theory, not practice. This is not merely a flaw in policy; it’s a reflection of who we are as a society. Do we allow gaps to grow unchecked, or do we act decisively to close them? Their next meal shouldn’t be an afterthought—it should remind us all that fairness starts at the table.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

- $2 Trillion by 2050? Manila’s Economic Fantasy Flimsier Than a Taho Cup

Leave a comment