By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — February 26, 2025

ON Dinagat Island, a speck of green off Mindanao’s coast, Maria Tumulak wakes before dawn. Her bamboo hut clings to a hillside once shrouded in towering dipterocarps—giants of the Philippine forest. Now, the canopy is thinning. At 53, Maria, a member of the Mandaya Indigenous group, treks deeper each day to gather rattan, her family’s lifeline. “The trees are disappearing,” she tells me, her voice steady but her eyes weary. “And with them, our way of life.” The Philippine Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) just dropped a bombshell: of the country’s 15 million hectares of forest lands, only 7 million remain forested. That’s a crisis measured not just in hectares, but in lives like Maria’s.

This isn’t a new story—it’s a wound centuries deep. When Spanish colonizers arrived, forests blanketed 90% of the archipelago, a paradise of biodiversity. By the 20th century’s end, that had plummeted to 20%. The Marcos era turbocharged the plunder, handing logging concessions to cronies at a clip of 300,000 hectares a year. Today, the culprits are subtler but no less ruthless: mining companies, palm oil plantations, and a government that winks at illegal loggers. The Philippine Mining Act of 1995 practically invites forest clearance, while short-term logging permits—often under a decade—turn conservation into a punchline. Who replants when profit trumps patience?

The data is stark. From 1934 to 1988, 9.8 million hectares vanished. Illegal logging alone fells 47,000 hectares annually—three times Quezon City’s sprawl. Typhoons, a brutal constant, rip through weakened ecosystems, amplifying the loss. But numbers don’t bleed. Maria does. Her community’s ancestral domain, legally theirs under the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act, shrinks as mining firms encroach. The Mandaya once thrived here—hunting, weaving, praying to forest spirits. Now, poverty pushes them to slash-and-burn, a desperate act born of landlessness. “We don’t want to cut,” Maria says. “But where else do we go?”

Who profits? Not Maria. Not the subsistence farmers scraping by. It’s the timber barons, the mining magnates, the agribusiness giants shipping palm oil abroad. The Philippine economy hums—GDP grows—but the wealth pools in Manila penthouses, not Dinagat’s hills. Corruption greases the wheels: weak enforcement lets loggers roam free, while DENR officials, underfunded and outgunned, chase shadows. This isn’t just “crooked bureaucrats.” It’s a system rigged for extraction, rooted in colonial habits of treating land as loot.

Yet amid the wreckage, glimmers of hope flicker. In Palawan, the Tagbanua people guard their forests with ancestral wisdom—rotating harvests, planting native trees. Their deforestation rates are a fraction of the national average. The National Greening Program, aiming to reforest 3 million hectares by 2028, has planted 1.83 billion seedlings since 2011. Satellite imagery tracks progress, exposing illegal cuts in real time. Community-based forestry agreements, empowering locals like the Tagbanua, have slowed forest loss in spots like Nueva Ecija. These aren’t cures—they’re bandages—but they work.

Why do so many efforts fail? Look at the past. The NGP’s tree survival rate hovers at 61%, far below its 85% goal. Corruption siphons funds; seedlings die untended. Laws exist—logging bans, protected areas—but enforcement is a ghost. Poverty gnaws at conservation: without jobs, farmers like Maria’s neighbors turn to charcoal-making. Power resists change. Mining firms lobby hard; officials pocket bribes. The DENR’s new push to map 1.2 million hectares for reforestation is bold, but will it outlast the next typhoon—or the next election?

One solution towers above: governance with teeth. Strengthen law enforcement, and you don’t just stop loggers—you enable everything else. Crack down on illegal cuts, and community projects flourish. Punish corruption, and funds reach the soil. It’s not sexy, but it’s systemic. Pair it with livelihoods—eco-tourism for the Mandaya, agroforestry for upland farmers—and you hit root causes, not symptoms. Success isn’t just hectares regained. It’s Maria’s grandchildren weaving rattan again. It’s carbon sinks thriving, flood risks dropping, species like the Philippine eagle soaring.

I ask Maria what she’d tell Manila’s leaders. “See us,” she says. “Not just the trees.” She’s right. This crisis isn’t abstract—it’s personal. Readers, demand transparency: push your governments to fund satellite monitoring, not photo-op tree plantings. Policymakers, back governance reforms—jail loggers, not just fines—and tie aid to jobs for forest folk. The Philippines can’t wait. Neither can Maria. Seven million hectares is a warning. Act now, or mourn a paradise lost.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

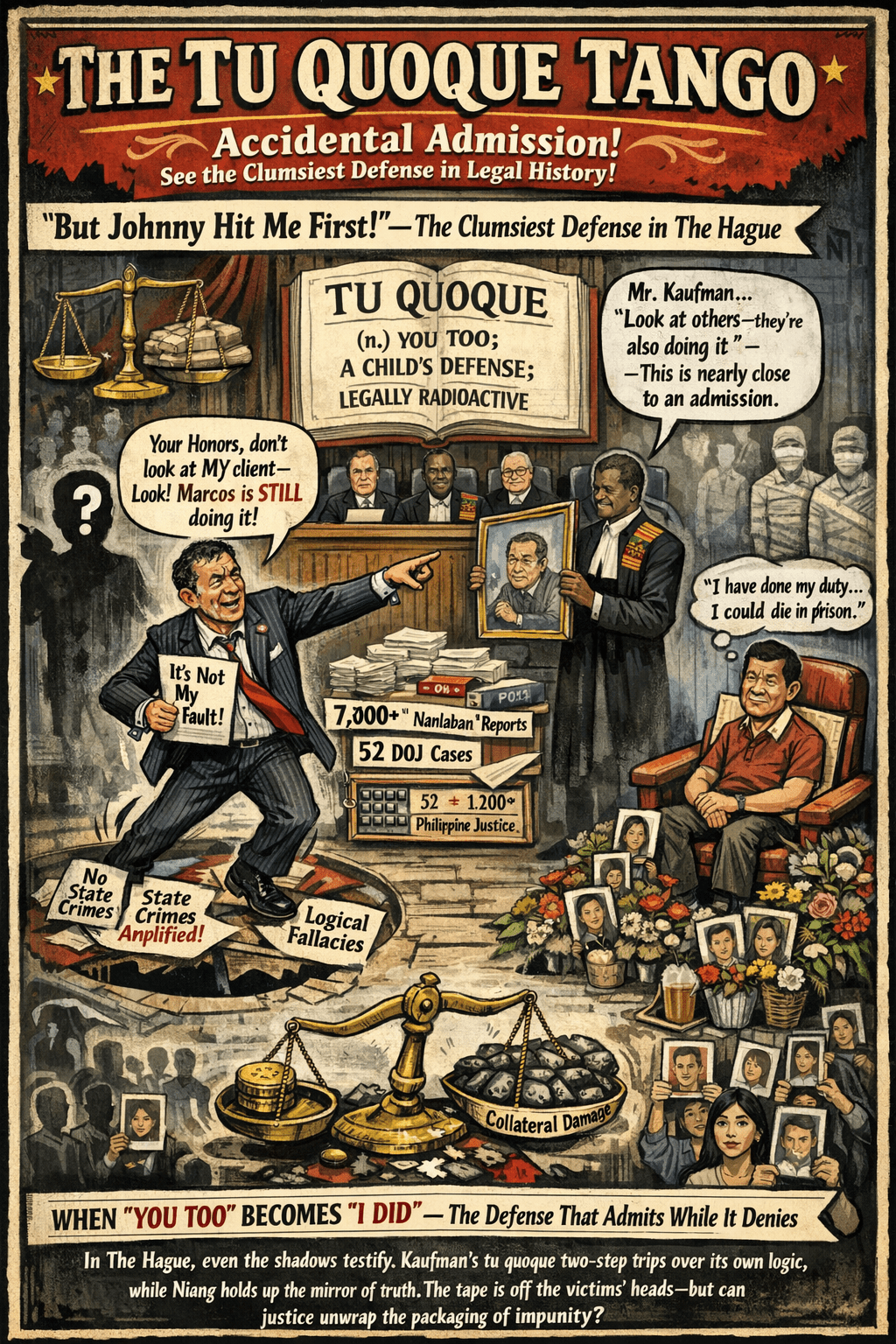

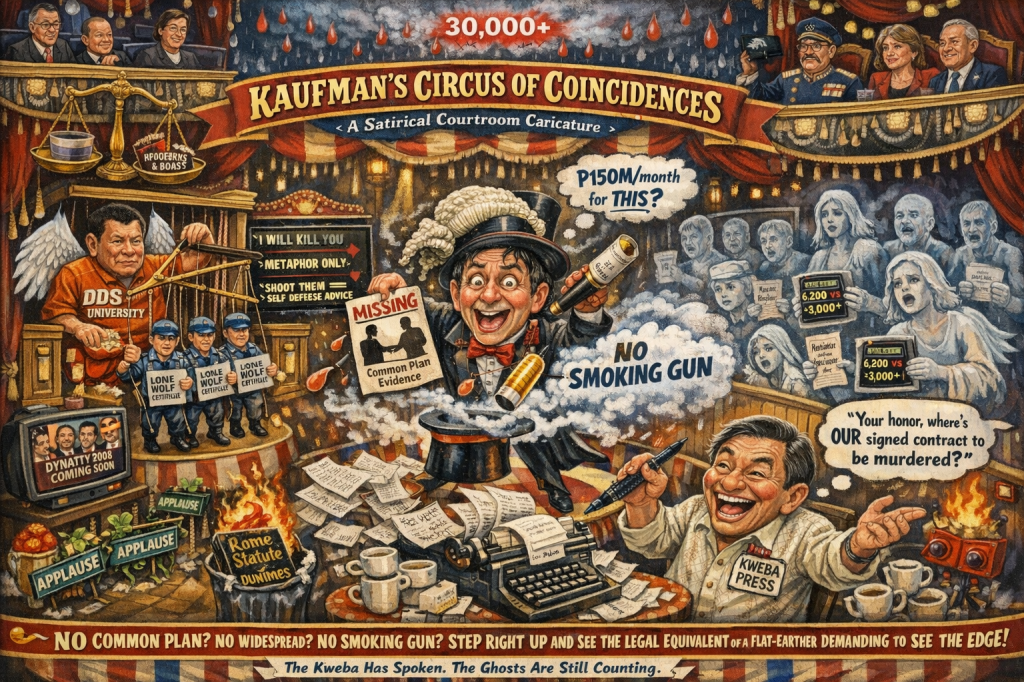

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment