By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — March 5, 2025

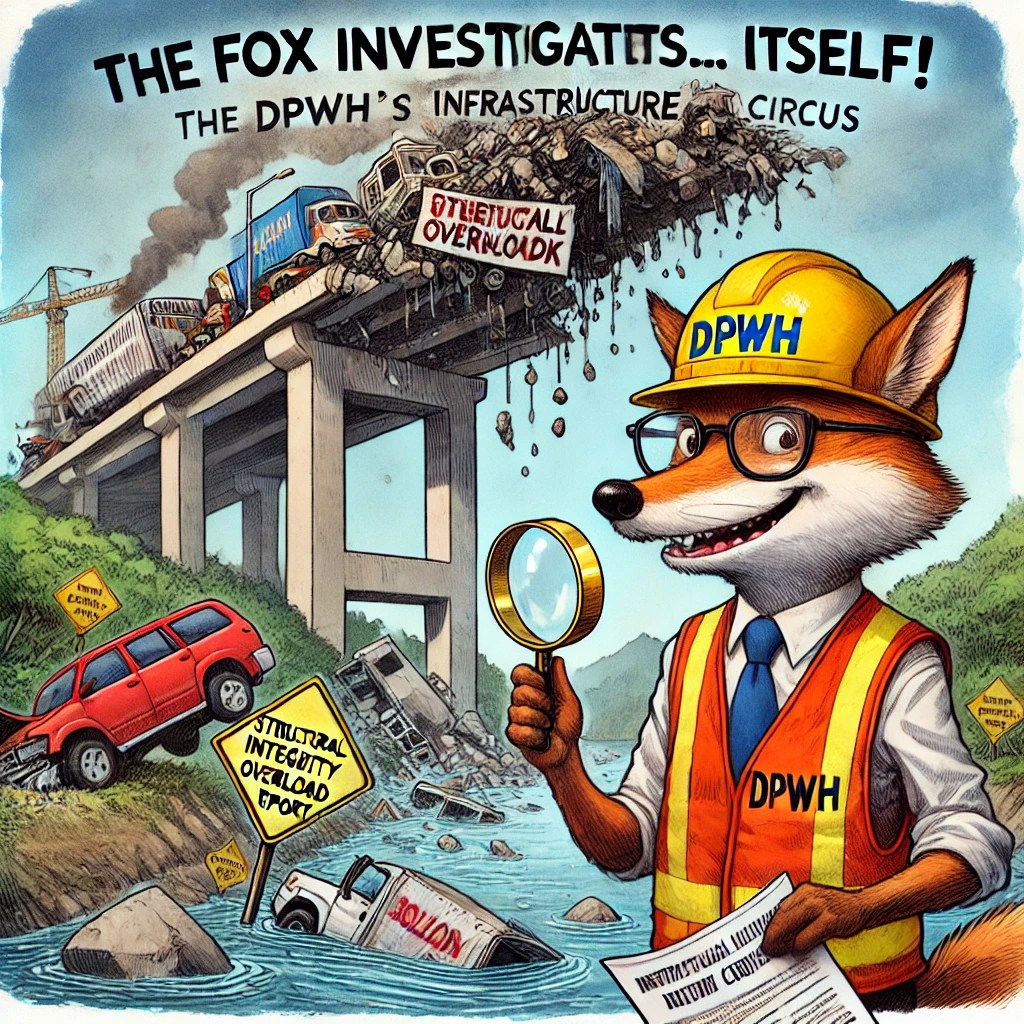

When the DPWH Plays Judge, Jury, and Executioner, Who Wins? Spoiler: Not the Public

Picture this: a shiny new bridge, a billion-peso ribbon-cutting photo op, and then—crash—60 meters of concrete and steel plunge into the Cagayan River, taking four vehicles with it. The Cabagan-Sta. Maria Bridge collapse on February 27, 2025, isn’t just a structural failure; it’s a screaming neon sign of systemic rot in Philippine public works. And now, Senate President Francis “Chiz” Escudero wants the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH)—the very agency that birthed this disaster—to lead the investigation. If irony were a construction material, this would be a skyscraper.

Let’s cut through the bureaucratic fog with a legal machete. Having the DPWH investigate its own failure isn’t just a conflict of interest; it’s a masterclass in self-absolution. Republic Act No. 6713, the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials, defines a conflict of interest as any situation where a public official’s duties could be swayed by personal stakes. Here, the DPWH isn’t just a bystander—it’s the overseer of the project, from procurement to ribbon-cutting. Asking it to probe itself is like handing a fox a flashlight and saying, “Go find out who ate the chickens.” The result? A predictable whitewash where inconvenient truths—like shoddy oversight or cozy contractor kickbacks—get buried under a pile of technical jargon about “overloading.”

Liability Roulette: Who Pays When the Bridge Falls?

Under Philippine law, the collapse isn’t a whodunit—it’s a who-pays-and-how-much. Article 1723 of the Civil Code is crystal clear: if a structure collapses within 15 years due to construction defects, the contractor and supervising engineer are on the hook. The Cabagan-Sta. Maria Bridge, completed a scant year ago on February 1, 2024, falls squarely in this window. If R.D. Interior, Jr. Construction cut corners—say, swapped Grade A steel for something cheaper—or if the DPWH’s design was a blueprint for disaster, liability should rain down like concrete shards.

But here’s the kicker: Republic Act No. 9184, the Government Procurement Reform Act, governs this mess too. It mandates transparency and accountability in public projects, yet the DPWH’s track record suggests neither. Was the bidding process a sweetheart deal? Did oversight turn a blind eye to substandard materials? The law demands answers, but with the DPWH holding the reins, don’t hold your breath. Escudero’s hedging—“if the design’s defective, liability shifts”—sounds reasonable until you realize the DPWH controls that narrative. Overloading by a 102-ton truck might be the spark, but a bridge built to code shouldn’t buckle like a house of cards.

Politicians vs. Engineers: A Cage Match of Egos and Excuses

Escudero’s call for DPWH leadership exposes a deeper fault line: the clash between political grandstanding and technical rigor. Politicians love a soundbite—“heads will roll,” Marcos thunders—but when the investigating agency is the accused, those heads stay firmly attached. The DPWH has the engineers, sure, but its bureaucrats are political animals, not truth-seekers. Republic Act No. 6713 demands public officials prioritize the public good over personal interest, yet self-investigation reeks of self-preservation.

Contrast this with the Supreme Court’s stance in Faj Construction & Development Corp. v. Saulog (G.R. No. 200759, 2015). The Court didn’t mince words: contractors bear the burden of defective work. If the DPWH’s design or supervision failed, it’s not just the contractor’s neck on the line—agency officials could face administrative or criminal heat. But when the DPWH doubles as investigator, the technical autopsy becomes a political cover-up. Why probe too deep when the findings might indict your own?

Deja Vu All Over Again: Self-Investigation’s Hall of Shame

This isn’t the Philippines’ first rodeo with self-investigating flops. Remember the 2013 Cebu Bus Rapid Transit fiasco—cost overruns, delays, and a DPWH-led “probe” that ended in shrugs and finger-pointing at “unforeseen circumstances”? Or the 2004 MacArthur Highway collapse, where a DPWH investigation blamed “natural wear” while locals whispered of substandard concrete and phantom inspections? Even Italy, corruption’s poster child, sidestepped self-investigation after the 2018 Genoa Morandi Bridge collapse, opting for an independent commission instead.

The Cabagan-Sta. Maria debacle fits this pattern like a glove. A DPWH-led probe risks the same old song: technical excuses, scapegoated truck drivers, and zero accountability for the suits who signed off on a billion-peso boondoggle. Supreme Court precedent—like City of Manila v. Laguio (G.R. No. 118127, 2005)—warns against government overreach without oversight. Letting the DPWH run this show isn’t just absurd; it’s a legal travesty.

Fixing the Unfixable: Reforms That Might Actually Work

Enough hand-wringing—let’s talk solutions. This bridge didn’t just collapse; it exposed a system begging for a wrecking ball. Here’s how to rebuild trust and infrastructure that doesn’t kill people:

- Ban the Fox from the Henhouse: Strip the DPWH of investigative powers in its own failures. Stand up an Independent Infrastructure Review Commission—think engineers, lawyers, and ethicists with no DPWH ties.

- Liability That Bites: Amend Article 1723 to include mandatory joint and several liability for contractors and supervising agencies. Couple this with RA 6713 sanctions: automatic suspension for DPWH officials during probes.

- Procurement Purge: Overhaul RA 9184 enforcement. Mandate third-party audits during construction, not after the rubble settles. Blacklist firms like R.D. Interior, Jr. Construction for a decade if found culpable.

- Supreme Oversight: Push the Supreme Court to fast-track infrastructure liability cases. A special docket for public works disasters would deter the DPWH’s “we’ll outlast the outrage” strategy.

- Whistleblower Shield: Strengthen RA 6713’s ethics code with protections for those exposing corruption. Offer immunity and rewards for evidence of graft or negligence.

The Bottom Line: Accountability or Bust

The Cabagan-Sta. Maria Bridge collapse isn’t an isolated oopsie—it’s a symptom of a public works apparatus that’s structurally unsound. Letting the DPWH investigate itself is like asking a toddler to critique its own tantrum. Philippine law—from the Civil Code to RA 9184—demands accountability, not excuses. The Supreme Court has the tools to punish failure, but only if the system lets it.

Marcos wants heads to roll? Start with the architects of this farce—figuratively, of course. Escudero’s faith in DPWH expertise is touching, but expertise without impartiality is just a fancy word for cover-up. The public deserves bridges that stand and probes that sting. Anything less is just more concrete in the river—and more blood on the ledger.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment