By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — March 7, 2025

ON March 4, 2025, the Commission on Elections (Comelec) First Division handed down a decision that shocked no one—and disappointed everyone. By dismissing the disqualification petition against five members of the Tulfo family over a missing document, Comelec didn’t just sidestep the issue of political dynasties; it exposed a legal system where technicalities trump justice, and power trumps principle. This isn’t just a story about the Tulfos; it’s a story about how the law fails the people it’s supposed to protect. Let’s unpack this mess and see what it means for the future of Philippine democracy.

1. Legal Technicalities: The Constitution’s Hostage Crisis

Comelec’s COC Obsession: Death by Paperwork

Under Rule 23 of the Comelec Rules of Procedure, a petition to disqualify a candidate must be accompanied by all pertinent documents—chief among them, the respondent’s COC. The First Division’s ruling hinged on petitioner Virgilio Garcia’s failure to include these, deeming the petition “insufficient in form.” This isn’t a mere clerical oversight; it’s a foundational requirement to verify candidacy details and ensure proper service. Without the COCs, the Comelec couldn’t confirm the Tulfos’ candidacies or whether they’d been notified—a due process non-starter. The rigidity of this rule is defensible in theory, but in practice, it’s a procedural guillotine that decapitates cases before they can breathe.

Article II, Section 26: The Magna Carta’s Empty Promise

The 1987 Constitution’s Article II, Section 26 boldly declares: “The State shall guarantee equal access to opportunities for public service and prohibit political dynasties as may be defined by law.” The Tulfos—Erwin, Ben, Jocelyn, Ralph Wendel, Wanda, and incumbent Senator Raffy—represent a textbook dynasty: six family members poised to dominate the 20th Congress. Yet, the provision’s caveat—“as may be defined by law”—renders it impotent without enabling legislation. Nearly 40 years post-EDSA, Congress, a veritable dynasty clubhouse, has predictably failed to act. The Comelec, bound by this legislative vacuum, can’t enforce what doesn’t exist, leaving Garcia’s constitutional argument dead on arrival.

Congress’s Dynastic Black Hole: Self-Preservation Over Democracy

The absence of an anti-dynasty law isn’t an oversight; it’s a feature of a legislature where clans like the Tulfos, Marcoses, and Dutertes reign supreme. The irony is palpable: a body tasked with regulating itself has zero incentive to do so. This vacuum isn’t just a gap—it’s a chasm that swallows democratic ideals whole, ensuring that Article II, Section 26 remains a noble sentiment rather than a legal weapon.

Supreme Court’s Cop-Out: Passing the Buck Since ’87

The Supreme Court has consistently held that Article II, Section 26 isn’t self-executing. In Navarro v. Ermita, G.R. No. 180050, April 12, 2011, 648 SCRA 400, it ruled that constitutional provisions requiring legislative action lack force absent an enabling statute. Similarly, in Mendoza v. Commission on Elections, G.R. No. 188308, October 15, 2009, 603 SCRA 692, the Court upheld Comelec’s dismissal of a dynasty-based disqualification petition, reinforcing that substantive claims like Garcia’s crumble without statutory backing. The judiciary’s hands are tied, but its deference to Congress’s inaction feels less like restraint and more like complicity in dynasty entrenchment.

2. Procedural Blunders: Justice Smothered by Red Tape

Garcia’s Fatal Fumble: A Lawyer’s Nightmare

Garcia’s omission of the COCs wasn’t just sloppy—it was fatal. Comelec Resolution 11046 mandates these documents as the bedrock of verification. Without them, the petition couldn’t proceed to substantive review, a failure Garcia, a retired brigadier general and lawyer, should’ve anticipated. Was this incompetence, or a rushed filing driven by political urgency? Either way, it’s a stark lesson: in election law, dotting i’s and crossing t’s isn’t optional.

Election Law’s Broken Record: Same Script, Different Dynasty

This isn’t an isolated fumble. Election challenges in the Philippines—disqualification petitions, COC cancellations—routinely crash on procedural shoals. From Poe-Llamanzares v. Comelec, G.R. Nos. 221697 & 221698-700, March 8, 2016, 786 SCRA 1, to countless local races, technical dismissals are the norm, not the exception. The system rewards precision but punishes haste, often leaving legitimate grievances—like dynasty proliferation—unheard. This pattern suggests a deeper malaise: a legal framework that prioritizes process over justice, shielding incumbents and dynasts from scrutiny.

Procedural Walls: Efficiency or Elite Protection?

Comelec defends these hurdles as necessary for order—ensuring petitions are serious, verifiable, and fair to respondents. Fair enough. But when procedural rigor becomes a fortress against substantive review, it’s less about efficiency and more about gatekeeping. The COC requirement, while logical, doubles as a convenient escape hatch for cases threatening the status quo. In a dynasty-dominated landscape, this smells suspiciously like design, not accident.

3. Fallout Frenzy: Winners, Losers, and Democracy’s Casualties

Garcia’s Double Whammy: Outgunned and Outlawyered

Garcia, running against Ralph Tulfo in Quezon City, wears two hats: legal advocate and political rival. His petition’s dismissal weakens his campaign, leaving him to face a Tulfo juggernaut without the disqualification card. As a lawyer, his credibility takes a hit—failing to clear a basic procedural bar isn’t a good look. Politically, he’s left grasping for traction, a cautionary tale for challengers banking on legal gambits.

Voters Screwed: Dynasties 1, Choice 0

Voters in Quezon City and beyond lose most. Six Tulfos in Congress isn’t just a family reunion—it’s a consolidation of influence that shrinks political diversity. Article II, Section 26 promises “equal access,” but without enforcement, voters get dynastic monopolies instead. The electorate’s voice is muffled when clans crowd the ballot, a betrayal of representative democracy’s core.

Democracy’s Slow Bleed: Another Nail in the Coffin

This case exposes a rotting foundation. When constitutional mandates languish and procedural traps shield dynasties, faith in the system erodes. The Philippines’ democracy, already strained by patronage and power concentration, takes another hit—cynicism festers as dynasts flourish.

Tulfo Takeover: Laughing All the Way to Congress

The Tulfos emerge unscathed, their legislative clout poised to grow. Six family members across Senate and House could steer policy, patronage, and pork with impunity. Erwin’s quip—“No anti-dynasty law yet”—is less a defense and more a taunt, spotlighting the system’s failure to rein them in.

4. Counterattack Blueprint: Slaying the Dynasty Beast

Comelec’s Last Stand: En Banc Hail Mary

Garcia can file a motion for reconsideration with the Comelec en banc within five days of the March 4 ruling (per Rule 19). Attach the COCs, fix the service issue, and pray the full Commission bites. Odds are slim—en banc rarely reverses on technicalities—but it’s a shot.

Supreme Court Showdown: Certiorari’s Uphill Battle

If en banc denies, a Rule 65 petition for certiorari to the Supreme Court is next, alleging grave abuse of discretion. Deadline: 30 days post-denial. The Court’s track record (Mendoza v. Commission on Elections, G.R. No. 188308, October 15, 2009, 603 SCRA 692) suggests skepticism, but a compelling due process angle—say, Comelec’s rigidity thwarting constitutional intent—might spark interest. Don’t hold your breath.

After the Vote: Electoral Tribunals’ Endgame

If the Tulfos win, jurisdiction shifts to the House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal (HRET) or Senate Electoral Tribunal (SET). Per Reyes v. Commission on Elections, G.R. Nos. 178831-32, July 30, 2009, 594 SCRA 717, post-proclamation challenges are their domain. Grounds like misrepresentation in COCs (Section 78, Omnibus Election Code) could work, but it’s a slow, uphill slog against entrenched winners.

Legislative Revolution: Smashing the Dynasty Machine

The nuclear option is an anti-dynasty law. Advocates must draft a bill defining “dynasty” (e.g., two or more relatives in office simultaneously) and push it through a reluctant Congress. Civil society pressure—petitions, protests—could force the issue, but don’t expect dynasts to vote against their DNA.

Conclusion: Time to Burn the Playbook

The Tulfo dismissal isn’t just a legal hiccup—it’s a damning indictment of a system that coddles dynasties while the Constitution collects cobwebs. Comelec’s procedural fetishism, Congress’s self-serving paralysis, and the judiciary’s hands-off stance form a perfect storm of inertia. For practitioners like Garcia, the lesson is clear: master the rules or get buried. For lawmakers, it’s a wake-up call—pass an anti-dynasty law or watch democracy atrophy. For civil society, it’s a rallying cry: amplify the noise, from streets to Senate, until Article II, Section 26 means something.

Recommendations

- Legal Practitioners: Triple-check filings. Hire a Comelec veteran to navigate the maze.

- Lawmakers: Introduce a dynasty bill with teeth—cap relatives in office, enforce it retroactively.

- Civil Society: Launch a “No Dynasty 2025” campaign—data-driven exposés, voter education, relentless pressure.

The Tulfos aren’t the problem; they’re the symptom. Fix the system, or kiss representative democracy goodbye.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

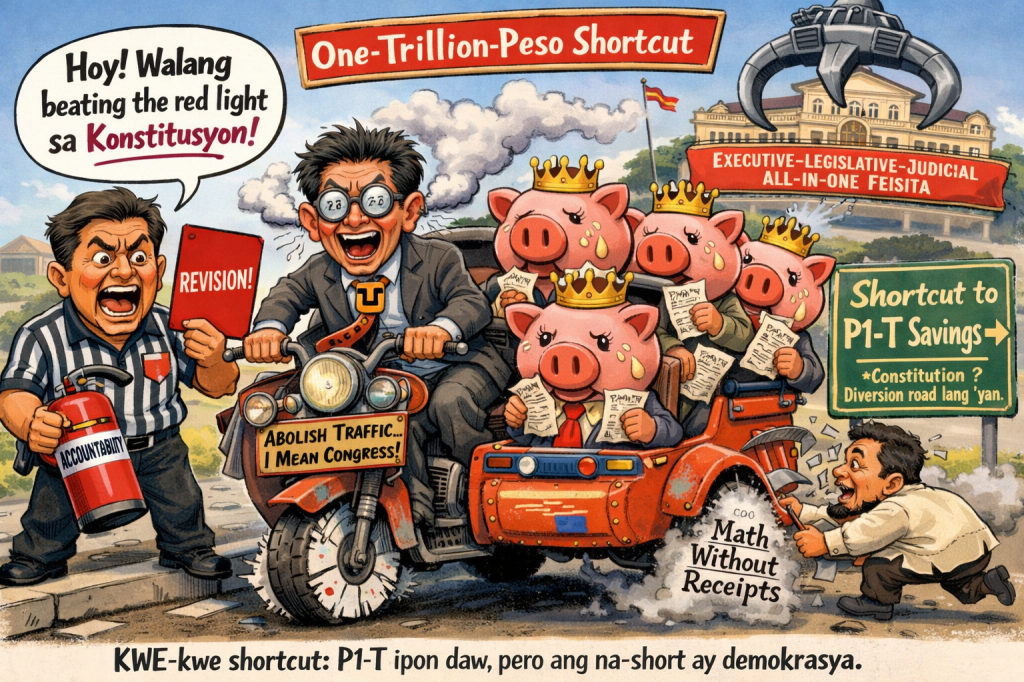

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

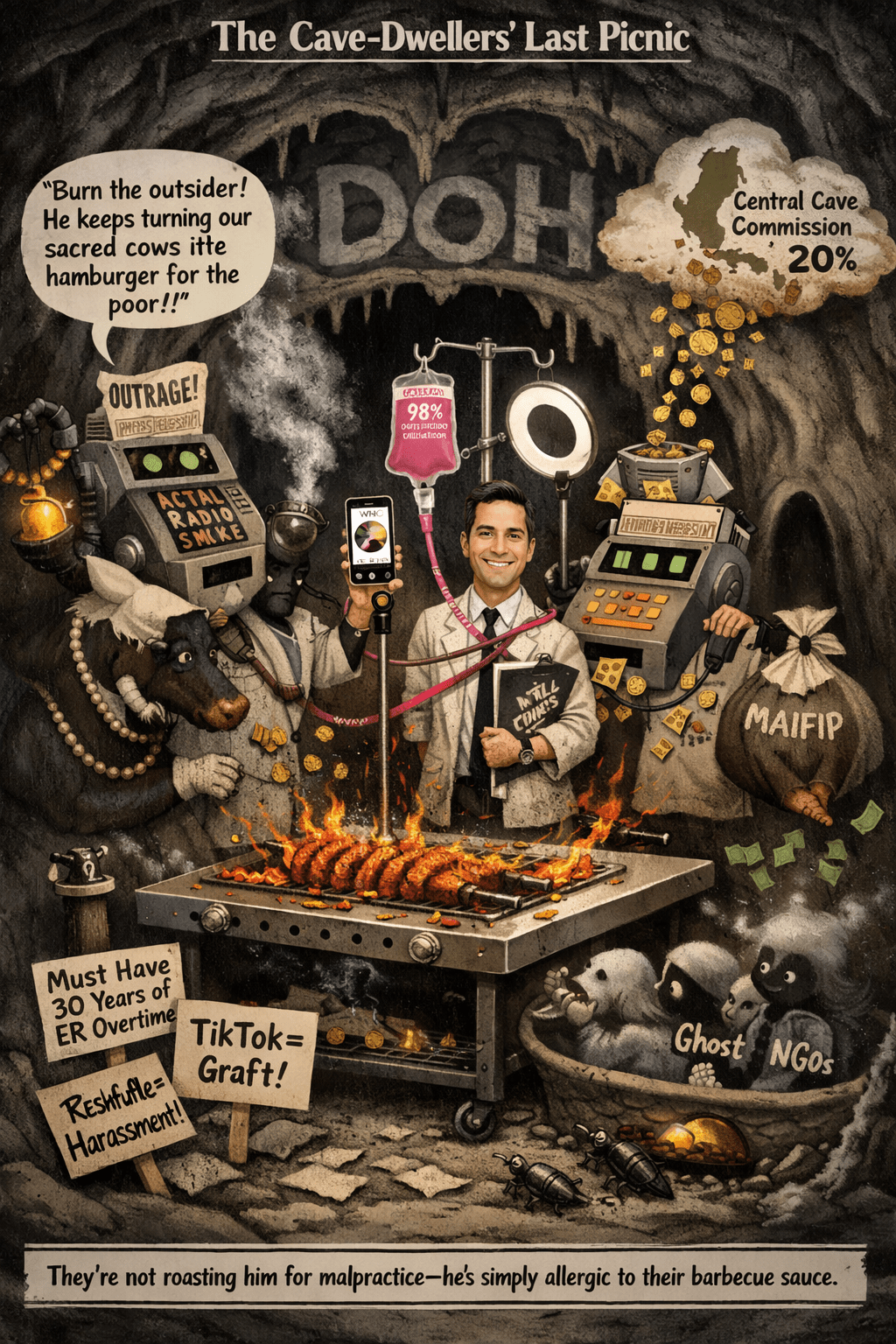

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment