By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — March 9, 2025

THE price of justice in the Philippines: apparently negotiable. When South Korean fugitive Na Ikhyeon walked free from his March 4, 2025 court hearing in Quezon City, it wasn’t an oversight—it was a transaction. CCTV footage now in Commissioner Joel Viado’s possession reveals the unthinkable: Bureau of Immigration personnel deliberately facilitating the escape of a man wanted for fraud. The grainy video, described officially as “damning evidence,” captures the moment integrity was sold and public trust betrayed in broad daylight.

This isn’t just a story of one man’s flight; it’s a searing indictment of a system rotting from within, where legal violations, corruption, and accountability gaps converge to erode public trust—and leave human lives in the lurch.

When Law Becomes a Laughingstock

Let’s start with the law—or rather, its flagrant violation. The BI personnel’s actions scream of “infidelity in the custody of a prisoner” under Article 224 of the Revised Penal Code, a crime punishable by up to six years in prison for negligence in allowing an escape. But the CCTV suggests more than negligence—collusion, a deliberate act that could trigger Article 223 (conniving with or consenting to evasion) or even Article 208 (prosecution of offenses; negligence and tolerance). These aren’t mere technicalities; they’re the legal backbone meant to ensure public officers don’t turn jailers into accomplices. Yet here we are, watching that backbone crumble.

The government’s response raises its own red flags. Viado’s “immediate termination” of the implicated officials sounds decisive, but it sidesteps the Administrative Code of 1987, Book V, Section 38, which mandates notice and a hearing before dismissal. The Supreme Court, in Lumiqued v. Exevea (1997), was unequivocal: administrative due process isn’t optional. Did these officers get their day to explain, or were they sacrificed for optics?

And what of the criminal cases Viado says are being prepared? Rule 112 of the Rules of Court requires a preliminary investigation before charges stick—announcing guilt via press release risks tainting the presumption of innocence, a principle enshrined in the 1987 Constitution and reinforced in People v. Leviste (1930). The law demands rigor, not rhetoric.

Corruption’s Chokehold on Justice

This isn’t an isolated lapse—it’s a symptom of systemic rot within the BI. The agency has long been a whispered synonym for corruption, from past extortion scandals to allegations of visa-fixing. The Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act (RA 3019) targets such abuses, with Section 3(e) penalizing acts causing “undue injury to any party” through manifest partiality. If bribery greased Na’s escape—a possibility the CCTV hints at but doesn’t prove—Section 7(d) of RA 6713, the Code of Conduct for Public Officials, was also shredded, forbidding solicitation of gifts. The Supreme Court’s ruling in Mondejar v. Buban (2007) set a stern precedent: public officers who betray their posts for personal gain face not just jail but a legacy of disgrace—a warning these BI agents ignored.

How did it come to this? The BI’s failure to secure a high-profile detainee like Na exposes a lack of oversight that violates the Government Auditing Code (PD 1445). Where were the internal controls, the audits, the training to spot a bribe before it’s taken? Public administration scholars would call this a classic accountability gap—when institutions prioritize survival over service, the public pays the price. Viado’s pledge of an internal audit of high-risk cases is a start, but why wasn’t it done before Na walked free?

The Accountability Mirage

Viado deserves praise—let’s not mince words. His swift sackings, his vow that “the days of corruption are numbered,” his unyielding “walang sasantuhin” (no one will be spared) stance—these are the cries of a leader refusing to let his agency drown in disgrace. He’s turning a scandal into a clarion call, framing it as a “turning point” for the BI. The man’s moral clarity cuts through the bureaucratic fog like a laser.

Yet even his vigor must bow to scrutiny. Preventive suspensions, as he’s ordered, are legal under Section 51 of the Administrative Code, but the Supreme Court in Layug v. Sandiganbayan (2001) warned they’re a shield, not a sword—suspicion alone doesn’t suffice. Does the evidence beyond the CCTV, like witness testimonies Viado cites, hold up? Procedural justice demands it.

Then there’s the Department of Justice’s supposed takeover, a claim the news report floats but can’t nail down. If true, it’s within the DOJ’s purview under the Administrative Code, but without evidence of a formal order, it smells of political theater. The Supreme Court in Crespo v. Mogul (1987) reminded us: once a case hits court, the judiciary, not the executive, calls the shots. Viado’s handing off to prosecutors is proper, but any whiff of overreach could undermine the process he’s championing.

Faces of a Broken System

Behind the legal jousting and institutional failures lies a human story too easily forgotten. Na Ikhyeon isn’t just a name on a warrant—he’s a man accused of defrauding countless victims in South Korea, perhaps Filipinos too, given his local estafa case. Every day he’s free, those victims wait longer for justice, their savings stolen, their trust in systems shattered.

What of the honest BI officers, tarred by their colleagues’ deeds, now facing public scorn? And consider the Filipino public, who fund this agency through taxes, only to see it falter when it matters most. Article XI, Section 1 of the Constitution declares public office a public trust—when that trust breaks, the human cost is incalculable.

Think of a mother in Seoul, cheated out of her life’s earnings by Na, watching this unfold. Does she wonder if Philippine corruption robbed her of closure? Or a BI clerk in Manila, diligent and underpaid, dreading the next headline. These are the faces of institutional failure, the ones who suffer when accountability frays.

Blueprint for Redemption

Viado’s response, while laudable, isn’t enough. The BI—and the Philippines—need reform that digs to the roots.

- Enforce Due Process Relentlessly: No terminations without hearings, no charges without investigations, as Lumiqued demands.

- Overhaul BI Oversight: Mandate quarterly audits under PD 1445, install real-time monitoring of detainees, and train officers to spot corruption’s early signs.

- Strengthen RA 3019 Enforcement: Create a dedicated anti-graft task force within the BI, insulated from political meddling, as Disini precedents urge.

- Protect Whistleblowers: RA 6713’s ideals mean nothing if insiders fear reprisal.

Politically, the Marcos administration must seize this moment. The BI’s credibility hangs by a thread; restoring it could bolster the government’s anti-corruption narrative. Inter-agency clarity—defining the DOJ’s role versus the BI’s—avoids the turf wars that erode trust. And legally, the CCTV evidence must face judicial scrutiny, not just public outrage, to ensure justice isn’t a casualty of haste.

The Reckoning We Can’t Ignore

Na Ikhyeon’s escape isn’t just a scandal—it’s a mirror. It reflects a nation wrestling with its institutions, a leader like Viado fighting to redeem them, and a people yearning for trust restored. Will we let this be another footnote in a saga of corruption, or the spark that forces change? The law, the system, the human stakes—they all demand the latter. Viado’s courage lights the way; now, the Philippines must follow.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

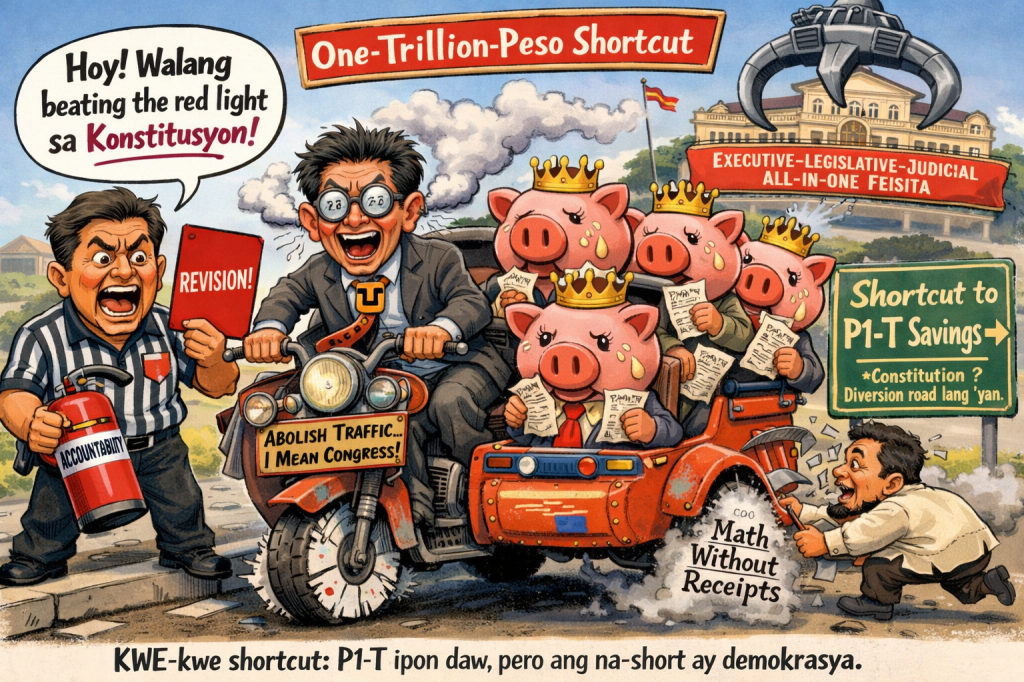

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

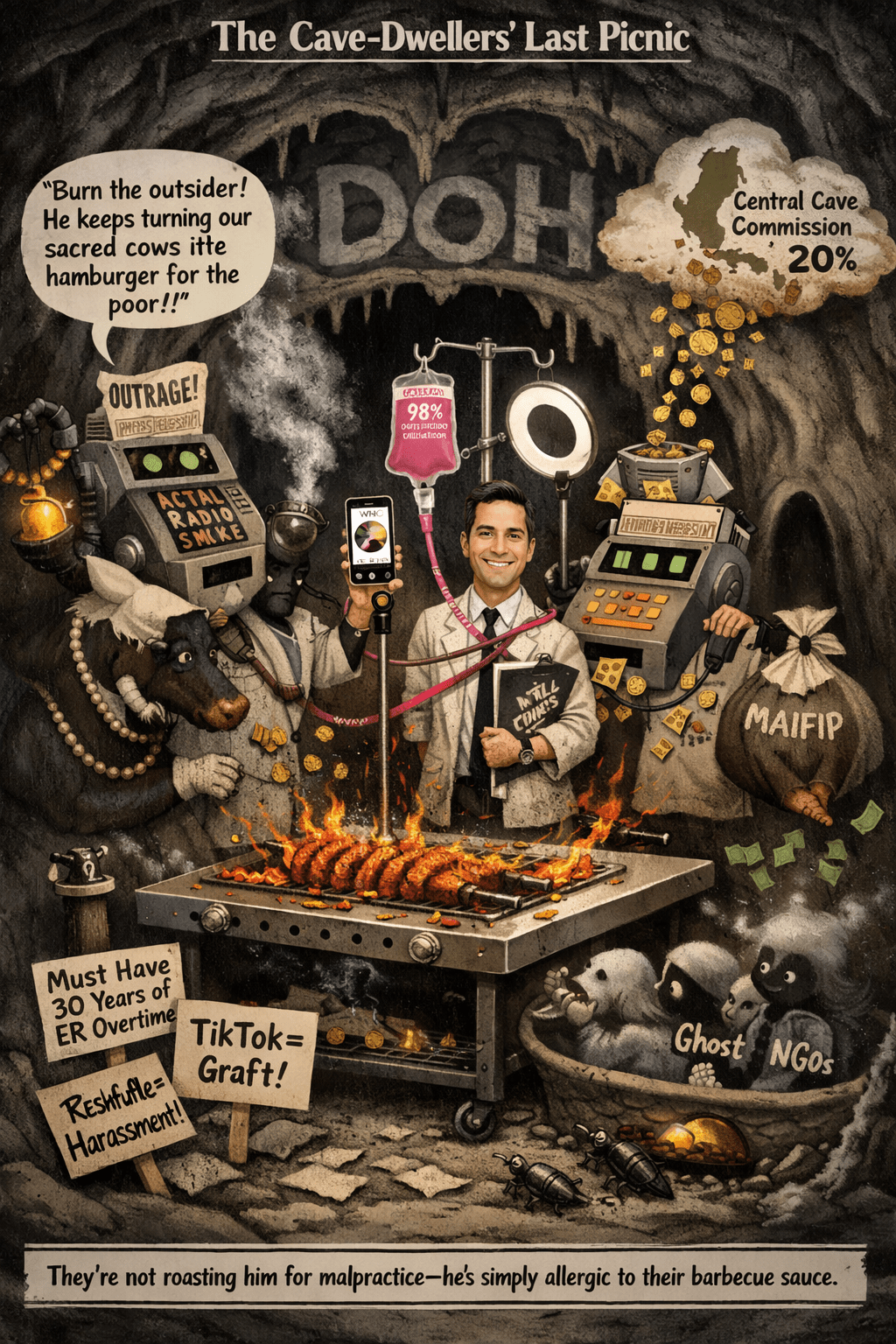

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment