By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — March 10, 2025

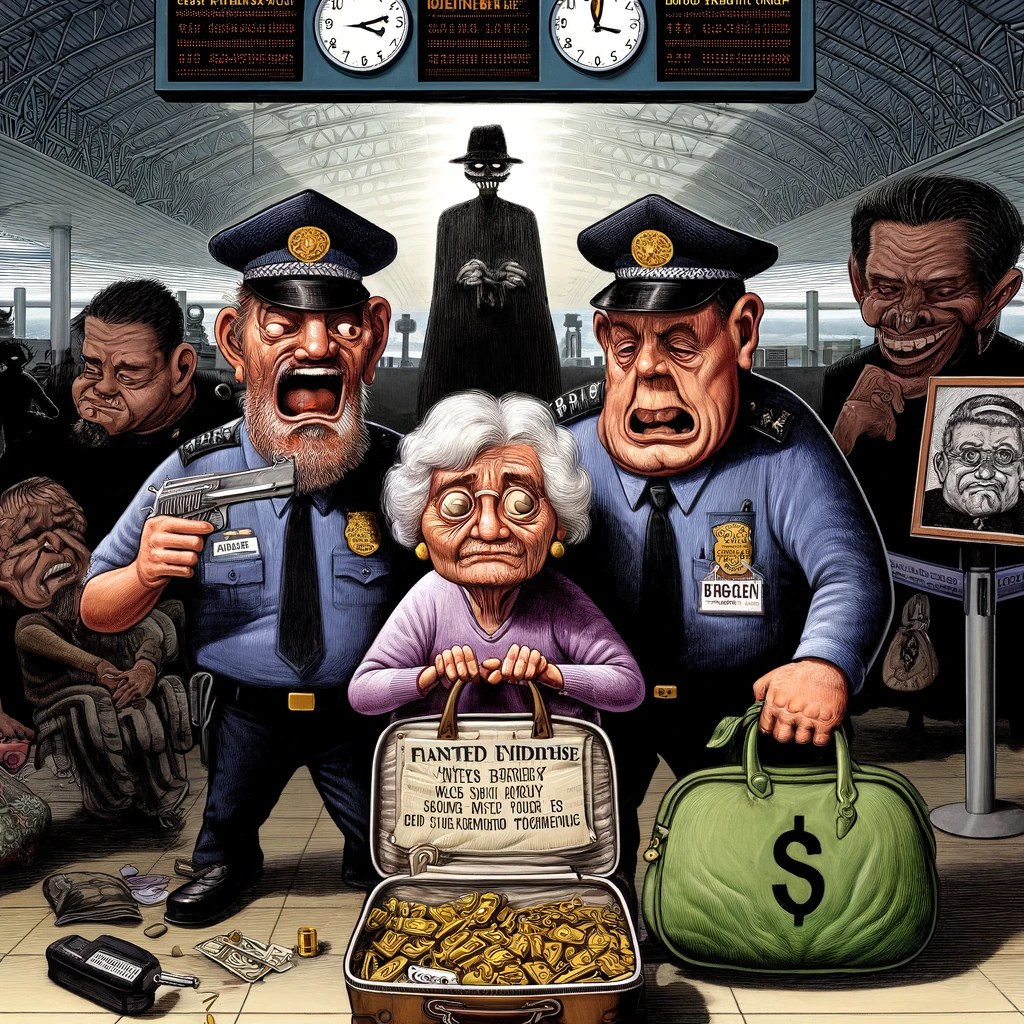

RUTH Adel was ready to board her flight to Vietnam, her 69-year-old hands clutching a boarding pass, her family buzzing with the excitement of travel. It was March 6 at NAIA Terminal 3 in Manila, and all she wanted was a smooth departure. Then, out of nowhere, security personnel from the Office of Transport Security (OTS) approached her at the gate. They claimed an X-ray had spotted an “anting-anting”—an amulet—in her luggage. When she asked what they meant, an officer, laughing casually, clarified: a bullet shell.

“I have not even seen a bullet in real life,” Ruth Adel wrote in a Facebook post from Vietnam, her words raw with disbelief and exhaustion after a harrowing ordeal. “They showed me a photo of a bag that wasn’t mine,” she recounted, “and when they searched mine, nothing was there.” At 69, she felt “so belittled,” so powerless, she said, her dignity stripped away at NAIA Terminal 3. Her blood pressure spiked, nightmares haunted her sleep, and what should have been a simple trip became a brush with an old, ugly scam: “tanim-bala,” or bullet-planting.

Adel’s story isn’t just hers—it’s a window into a systemic rot that has festered at Manila’s main airport since at least 2012, when the scheme first surfaced. Airport officials allegedly plant bullets in passengers’ bags, then exploit their panic—miss your flight or pay up—to extort money. It’s a shakedown dressed up as security, and it preys on the vulnerable: the elderly like Adel, overseas Filipino workers desperate to reach jobs abroad, tourists unfamiliar with the terrain. This isn’t a glitch in the system; it’s a feature of a deeper corruption that Philippine leaders have failed to uproot, despite promises and directives stretching back over a decade.

The Ghost of Scandals Past: Why “Tanim-Bala” Won’t Stay Buried

The “tanim-bala” scheme exploded into public view in 2015, during Benigno Aquino III’s presidency, with over 30 documented cases exposing a syndicate at NAIA. An American missionary, Lane Michael White, was detained after a bullet was “found” in his luggage; he claimed officials demanded 30,000 pesos (about $600 then) to let him go. The National Bureau of Investigation confirmed an extortion racket, yet few faced real consequences. In 2016, President Rodrigo Duterte, with his trademark bluster, ordered bullets confiscated without delay, vowing to make culprits “swallow” them. Travelers exhaled, thinking the nightmare was over.

Yet here we are in 2025, with Adel’s ordeal echoing White’s. Last March, a Thailand-bound woman faced a similar accusation, denied by OTS as her own doing. The pattern is clear: a brief lull, then a resurgence. Why does this persist? Because the system thrives on impunity. Duterte’s directive, like Aquino’s outrage, was loud but toothless—unenforced by a Department of Transportation (DOTr) that oversees OTS yet rarely disciplines it. The New Naia Corp., a private consortium running NAIA since September 2024, promised reform, but Adel’s case suggests they’ve inherited the mess without cleaning it up.

Legal experts I spoke with point to a glaring gap: no specific law targets “tanim-bala” as a distinct crime. “We rely on general provisions—falsification, coercion, graft—which are hard to prove without airtight evidence,” says Atty. Jose Manuel Diokno, a prominent Manila human rights lawyer. “Victims need video, witnesses, the bullet itself. Perpetrators know this and exploit it.” Adel’s video, where officers allegedly covered name tags, might help, but the deck is stacked against her.

Trapped at the Gate: When Power Laughs at the Powerless

Picture the scene: Adel, a retiree with no legal training, facing OTS officers armed with badges, X-ray machines, and the power to derail her life. She refused to leave the gate—boarding had started—but how many can? Overseas Filipino workers, who send home over $30 billion annually, often pay bribes to avoid missing flights that secure their families’ survival. Tourists, like a Japanese couple in 2015, fork over cash to escape detention in a foreign land. The elderly, like Adel, are soft targets—too rattled or frail to fight back.

“They laughed at me,” Adel recalled, her voice breaking. “As if my fear was a joke.” That laughter is the sound of unchecked power. OTS personnel, public officers under DOTr, operate in a bubble of presumed regularity—courts assume they’re honest unless proven otherwise. Yet their actions suggest a racket: inconsistent stories (luggage, then handbag), no bullet found, a retreat when filmed. This isn’t incompetence; it’s a calculated gamble that most won’t resist.

Civil society groups like the Philippine Alliance of Human Rights Advocates (PAHRA) see a broader failure. “It’s not just about a few bad apples,” says PAHRA’s Rose Trajano. “It’s a culture of corruption enabled by weak oversight and a justice system that rarely bites.” Data backs her up: the Ombudsman, tasked with probing public officers, boasts a 2% conviction rate for graft cases, per 2021 Sandiganbayan figures. Victims face a labyrinth—file with the Ombudsman, prosecutor, or courts—while perpetrators bet on their exhaustion.

Justice Denied: Why Victims Can’t Fight Back

Adel wants accountability, but the barriers are daunting. She’s in Vietnam now, 1,000 miles from Manila’s courts. Filing online with the Ombudsman or via proxy is possible—RA 6770 allows it—but does she know? Most don’t. A 2023 Transparency International report found Filipinos rank judicial access among the lowest in Southeast Asia. Legal aid exists, but public defenders are stretched thin, and private lawyers cost money Adel may not have.

Even with her video, justice is a long shot. “The burden of proof is crushing,” Diokno explains. “You need to show intent, identity, the act itself—against officers who control the scene.” In 2016, White’s case collapsed for lack of evidence; the DOJ cleared NAIA personnel, citing “no irregularities.” Adel’s age and trauma—she still has nightmares—make a prolonged fight unlikely. Perpetrators count on this: time, distance, and despair wear victims down.

Government officials deflect. DOTr Secretary Vince Dizon, responding hours ago to Adel’s case, announced the termination of involved OTS personnel, per an ABS-CBN post on X. It’s a start, but it’s reactive, not systemic. “We’ve heard this before,” Trajano counters. “Firings without structural change are theater.” Duterte’s 2016 order didn’t stop the 2024 incident or Adel’s. Why trust this now?

No More Excuses: How to Stop the Shakedown

Adel’s story demands more than outrage—it demands solutions.

- Legislation: Congress must pass a “Tanim-Bala Prevention Act,” defining bullet-planting as a specific offense with stiff penalties (10-15 years imprisonment) and flipping the burden: let accused officers prove innocence when evidence like Adel’s video emerges.

- Oversight: The DOTr must install independent oversight—an external board, not internal cronies—to audit OTS weekly, with public reports. Cameras at every checkpoint, tamper-proof and livestreamed, could deter scams; Adel’s footage proves their value.

- Victim Empowerment: The Ombudsman should launch a “Tanim-Bala Task Force” with a toll-free hotline and embassy support for overseas Filipinos, ensuring complaints like Adel’s are fast-tracked within 30 days, as RA 6770 permits. Free legal clinics at NAIA, run by groups like PAHRA, could guide travelers on their rights.

- Funding Reforms: New Naia Corp. must fund these reforms—call it a “security tax” on profits—proving privatization isn’t just a cash grab.

Adel deserves justice, not just sympathy. “I don’t want anyone else to feel this,” she told me, her eyes wet but resolute. Her voice is a plea to a nation that’s heard too many: end this disgrace. The Philippines can’t keep boarding planes on a runway of corruption. It’s time to ground “tanim-bala” for good—before the next Ruth Adel misses her flight, and her faith in home.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

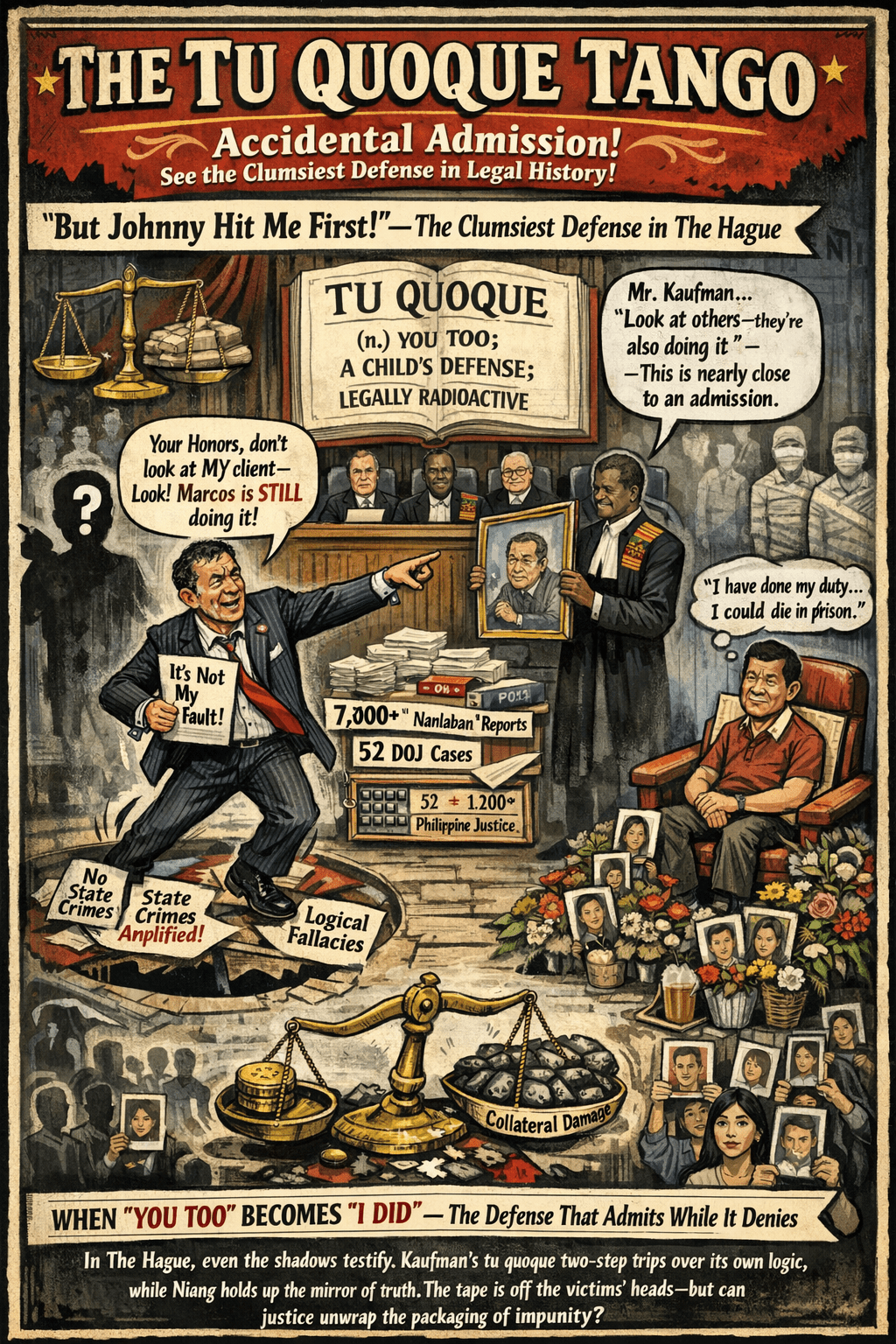

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment