By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — March 12, 2025

THE arrest of former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte on March 11, 2025, at Manila’s Ninoy Aquino International Airport is more than a sensational headline—it’s a high-stakes legal showdown pitting the International Criminal Court (ICC) against Philippine sovereignty, with Interpol acting as the enforcer. The arrest warrant, tied to Duterte’s brutal “war on drugs” that left thousands dead, has ignited a firestorm of legal and political questions: Does the ICC have jurisdiction? Was due process violated? And can the Philippines simply ignore The Hague? Let’s dissect this complex situation with the rigor it demands and the irreverence it deserves.

Jurisdiction Judo: Can the ICC Still Pin Duterte?

The ICC’s claim to jurisdiction is the first point of contention. Duterte’s camp, led by former Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea, argues that the Philippines withdrew from the Rome Statute in 2019, rendering the ICC’s authority null and void. However, Article 12(1) of the Rome Statute grants the ICC jurisdiction over crimes committed on the territory of a member state while it was still a member. Article 127(2) further clarifies that withdrawal does not absolve a state of its obligations for crimes committed prior to its exit.

Duterte’s drug war, which began in 2016 and continued until the Philippines’ withdrawal in 2019, falls squarely within this window. The Philippine Supreme Court affirmed this principle in Pangilinan v. Cayetano (2021), ruling that pre-withdrawal ICC jurisdiction remains valid.

Yet, Medialdea’s sovereignty argument isn’t entirely baseless. The Philippines’ withdrawal from the ICC was a defiant rejection of international oversight, rooted in Article II, Section 2 of the 1987 Constitution, which emphasizes an “independent foreign policy.” However, the ICC operates as a court of last resort and does not require a state’s consent to investigate. Legally, the ICC’s jurisdiction over pre-2019 acts is solid, regardless of Duterte’s protests.

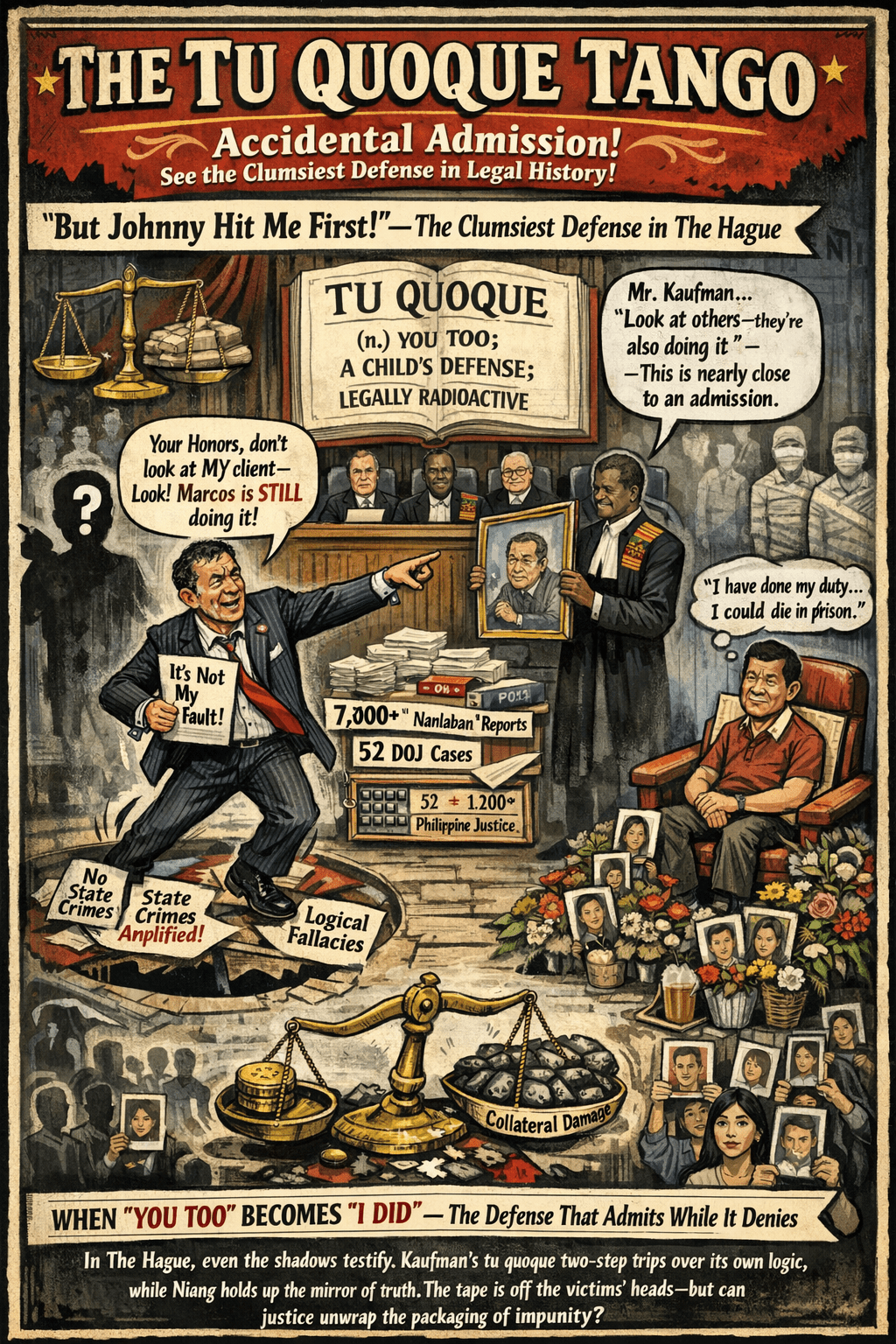

Due Process or Kangaroo Court?

Medialdea’s loudest complaint centers on due process—or the perceived lack thereof. He argues that Duterte was denied the opportunity to respond to charges before the arrest warrant was issued, a stark departure from Philippine legal norms. Under the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure (Rule 112), suspects in the Philippines are entitled to notice and a chance to respond before an arrest warrant is issued.

The ICC, however, operates differently. Article 58 of the Rome Statute allows a Pre-Trial Chamber to issue warrants based solely on the prosecutor’s evidence, without requiring input from the defendant. Notice is typically provided after the arrest, per Article 59. While this process may seem abrupt compared to Philippine standards, it is fully consistent with ICC rules, which prioritize speed and victim protection over pre-arrest debates.

Medialdea’s outrage is understandable, but legally irrelevant. The ICC is not bound by Philippine procedures, and its approach is designed to address the unique challenges of prosecuting international crimes. Still, the optics of a former head of state being arrested without prior notice are undeniably damaging, making the process appear more like a geopolitical power play than a fair judicial proceeding.

Complementarity Conundrum: Did Manila Drop the Ball?

The ICC’s principle of complementarity, enshrined in Article 17, dictates that the court only intervenes when a state is unable or unwilling to prosecute crimes domestically. Duterte’s defenders argue that the Philippines could handle the case under Republic Act No. 9851, its domestic law on crimes against humanity. However, the evidence suggests otherwise.

The 2019 petition in Baylon v. Duterte called for local investigations into the drug war killings but was met with silence. Official estimates place the death toll at 6,200, while human rights groups claim it could be as high as 30,000. Despite these staggering numbers, credible domestic investigations have been virtually nonexistent.

The ICC’s 2023 appeals ruling further undermined Manila’s claims of self-policing, finding no “genuine” effort to hold high-ranking officials accountable. Duterte’s own public statements—such as his explicit orders to “shoot and kill” suspects—only strengthened the case for ICC intervention. In short, the Philippines had its chance to address these crimes and failed, leaving the ICC to step in.

Sovereignty Showdown: Who’s the Boss?

At the heart of this case lies the tension between international justice and national sovereignty. Medialdea’s argument that the Philippines is no longer bound by the ICC’s authority taps into a legitimate grievance: why should a non-member state submit to the court’s jurisdiction? Article 127(2) of the Rome Statute clarifies that withdrawal eliminates future cooperation obligations but does not absolve a state of responsibility for pre-withdrawal crimes.

The Philippines’ decision to arrest Duterte through Interpol, despite its 2019 ICC withdrawal, demonstrates that Manila is still engaging with the international system, likely under Article 87’s non-member cooperation clause and Interpol’s red-notice mechanism. While the arrest may feel like a blow to Philippine sovereignty, it is legally justified under the terms of the country’s prior ICC membership.

Medialdea’s Claims: Hot Air or Hidden Gold?

Medialdea’s due process argument falls flat under ICC rules, which explicitly allow for warrants to be issued without prior notice to the defendant. His sovereignty argument carries more weight, but Article 127(2) and Interpol’s enforcement mechanisms undermine its legal viability. While his rhetoric may resonate politically, it does little to alter the legal reality.

Medialdea’s strongest card is not legal but political: by stoking nationalist sentiment, he could pressure the Marcos administration to delay or obstruct Duterte’s extradition to The Hague.

Warrant’s Legs and Enforcement Odds

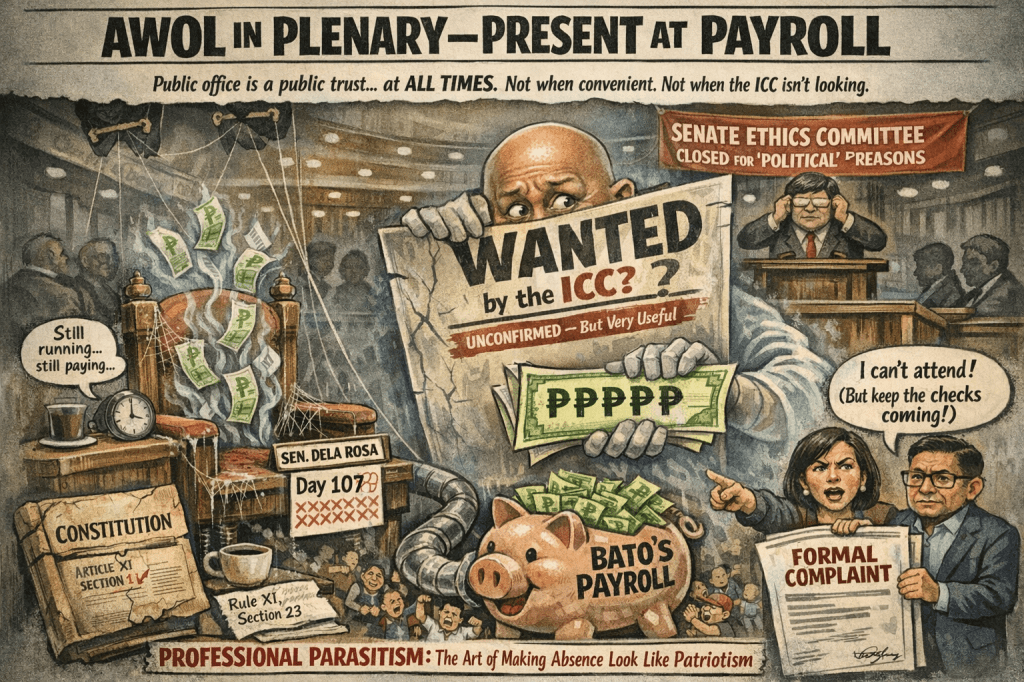

The ICC warrant is legally sound. Article 7 (crimes against humanity) covers Duterte’s alleged orchestration of mass killings, and his public statements provide ample evidence of intent under Article 30. However, enforcement remains uncertain. While Interpol has detained Duterte, his extradition to The Hague requires Philippine cooperation.

President Marcos Jr.’s strained relationship with Duterte suggests he may be willing to approve the extradition, but political pressure from Duterte’s base could complicate matters. The ICC, lacking its own enforcement arm, is ultimately dependent on Manila’s willingness to comply.

Playbook for the Players

- Duterte: Push for a domestic investigation under RA 9851 to challenge the ICC’s complementarity principle. If this fails, voluntary surrender to contest the evidence under Article 61 may be a better option than prolonged extradition limbo.

- Philippine Government: Cooperate minimally with Interpol but delay extradition to buy time and assess public sentiment. Cite sovereignty concerns under Article II of the Constitution to justify the delay.

- ICC: Leverage diplomatic pressure from allied nations to compel Philippine cooperation.

- Victims’ Advocates: Amplify the narrative of 30,000 deaths to maintain international attention and pressure on the Philippine government.

The Verdict: Justice vs. Realpolitik

Duterte’s arrest is a legal victory for the ICC, with jurisdiction, complementarity, and the Rome Statute holding up under scrutiny. However, enforcement remains a political minefield. While the Philippines may feel its sovereignty has been undermined, its pre-2019 ICC membership leaves it with little legal recourse.

The warrant is valid, the arrest is lawful, and Duterte is in custody—but whether he faces trial in The Hague or remains in Manila depends on the Marcos administration’s political will and the public’s reaction. For the victims of Duterte’s drug war, this is a small step toward justice—but it’s a step nonetheless.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment