By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — March 11, 2025

RODRIGO Duterte, the Philippines’ infamous “Punisher,” now wears the ultimate symbol of accountability: handcuffs. On March 11, 2025, the former president was hauled off at Ninoy Aquino International Airport (NAIA) under an ICC warrant, his “war on drugs” legacy reduced to a chilling statistic—30,000 dead, a number so staggering it could fill a city. This isn’t just another arrest; it’s a watershed moment for international justice, a former leader dragged into the dock despite his country’s defiant 2019 exit from the ICC. Strap in—this is a high-stakes legal thriller where blood, bureaucracy, and global power collide.

Here’s the full breakdown: from arrest to appeals, the charges pinning Duterte to the wall, the defenses he’ll throw like desperate spaghetti, and the fallout for everyone from Marcos Jr. to Manila’s grieving widows. We’ll dissect the Rome Statute, grapple with Philippine law, and offer a sharp-edged analysis of what this means for the global legal order. Spoiler alert: it’s messy, historic, and a crash course in why international law is both a noble endeavor and a diplomatic quagmire.

1. Procedural Pandemonium: From NAIA to The Hague – A Wild Ride Awaits

The ICC Gauntlet: Arrest to Judgment Day

Duterte’s arrest sets off a legal marathon under the Rome Statute’s unyielding scrutiny. First stop: a Philippine holding cell, courtesy of the PNP’s Criminal Investigation and Detection Group (CIDG). Rappler’s sources reveal key figures—Prosecutor General Richard Fadullon and Justice Undersecretary Felix Ty—lurking at NAIA, ready to facilitate the process. Article 59(1) mandates “immediate steps” to arrest and process the suspect under local laws. A Regional Trial Court will verify the warrant’s legitimacy and Duterte’s identity (Article 59(2))—no theatrics, just procedural rigor.

Next, it’s off to The Hague under Article 59(7), which requires surrender “without delay” after formalities are completed. At the ICC Detention Centre, Duterte will face the Pre-Trial Chamber for an initial hearing (Article 60)—charges will be read, and his rights outlined. The confirmation of charges hearing (Article 61) will test the evidence: police logs, Duterte’s incendiary speeches, and more. If the charges stick, the Trial Chamber takes over, likely resulting in years of courtroom battles. Regardless of the verdict, appeals (Article 81) could drag this saga into the next decade.

Jurisdiction Joust: The 2019 Walkout That Won’t Stick

The Philippines withdrew from the ICC in 2019, effective March 17, under Duterte’s leadership. So why is he still in the ICC’s crosshairs? Article 127(2) clarifies that withdrawal doesn’t nullify pre-exit investigations—such as the drug war’s 2011–2019 carnage. The Supreme Court’s Pangilinan v. Cayetano (G.R. No. 238875, 2021) reinforces this: past obligations remain binding. Duterte’s legal team will cry foul over sovereignty, but it’s a futile argument.

Interpol’s Red Notice: The Global Snare That Nailed Him

No ICC enforcement squad was needed—just Interpol’s Red Notice, a global “wanted” alert. While not a warrant, it serves as a neon sign for arrest and extradition. The Philippines, an Interpol member since 1950, couldn’t ignore it without damaging its international reputation. Marcos Jr., wary of direct ICC involvement, leaned on “Interpol duty” as a justification—a shrewd move consistent with the Interpol Constitution (Article 2) and transnational crime agreements. The PNP and DILG acted swiftly, proving that even a reluctant state can’t outmaneuver this system.

Philippine Lockup: A Quick Stop Before the Hague Express

RA 9851 (Section 17) authorizes holding ICC suspects for transfer. Duterte is in PNP custody—high-security, no presidential perks—while courts complete the necessary formalities. The Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure (Rule 113) govern arrests, but RA 9851 takes precedence for ICC cases. Purganan (G.R. No. 148571, 2002) confirms that extradition skips the usual drama—Duterte is Hague-bound faster than you can say “extrajudicial.”

2. Substantive Showdown: What’s Duterte Really Facing?

Article 7: The Crimes Against Humanity Hammer

The ICC is pursuing Duterte under Article 7(1)(a)—murder as part of a “widespread or systematic attack” on civilians. The drug war’s 30,000 deaths (per human rights groups, dwarfing the PNP’s 6,000 estimate) fit the bill. Prosecutors will argue the campaign was systematic (state-directed via kill orders) and widespread (spanning years and multiple cities). Article 7(2)(a) requires proof of intent; Duterte’s public threats are Exhibit A. Prosecutor v. Bemba (2016) set a precedent for systematic violence convictions—Duterte’s body count makes Bemba’s case look tame.

Article 28: Command Responsibility – The Boss Takes the Fall

Article 28(a) holds commanders accountable if they “knew or should have known” about crimes and failed to act. Duterte wasn’t just complicit—he was the architect, directing law enforcement and publicly endorsing killings. The ICTY’s Blaskić (2000) ruling established that public incitement demonstrates intent; Duterte’s rhetoric is a treasure trove for prosecutors. Article 28(b) may also implicate subordinates, but the primary target is the man at the top.

ICC Playbook: Lessons from the Big Leagues

The ICC has tackled state violence before. Prosecutor v. Al-Bashir (2009) saw Sudan’s ex-president indicted for genocide—though the warrant remains unexecuted, jurisdiction was affirmed. Prosecutor v. Kenyatta (2014) collapsed due to insufficient evidence—a cautionary tale for prosecutors building Duterte’s case. This could be the ICC’s landmark victory—or another near-miss.

Philippine Law’s Shadow Dance

RA 9851 mirrors Article 7, codifying crimes against humanity in Philippine law. Section 4’s “extermination” provision aligns with the drug war’s scale. While Marcos Jr. avoids direct involvement, the legal overlap validates the ICC’s charges. Estrada v. Desierto (2001) stripped immunity from ex-presidents, aligning Philippine law with the ICC’s no-exceptions approach.

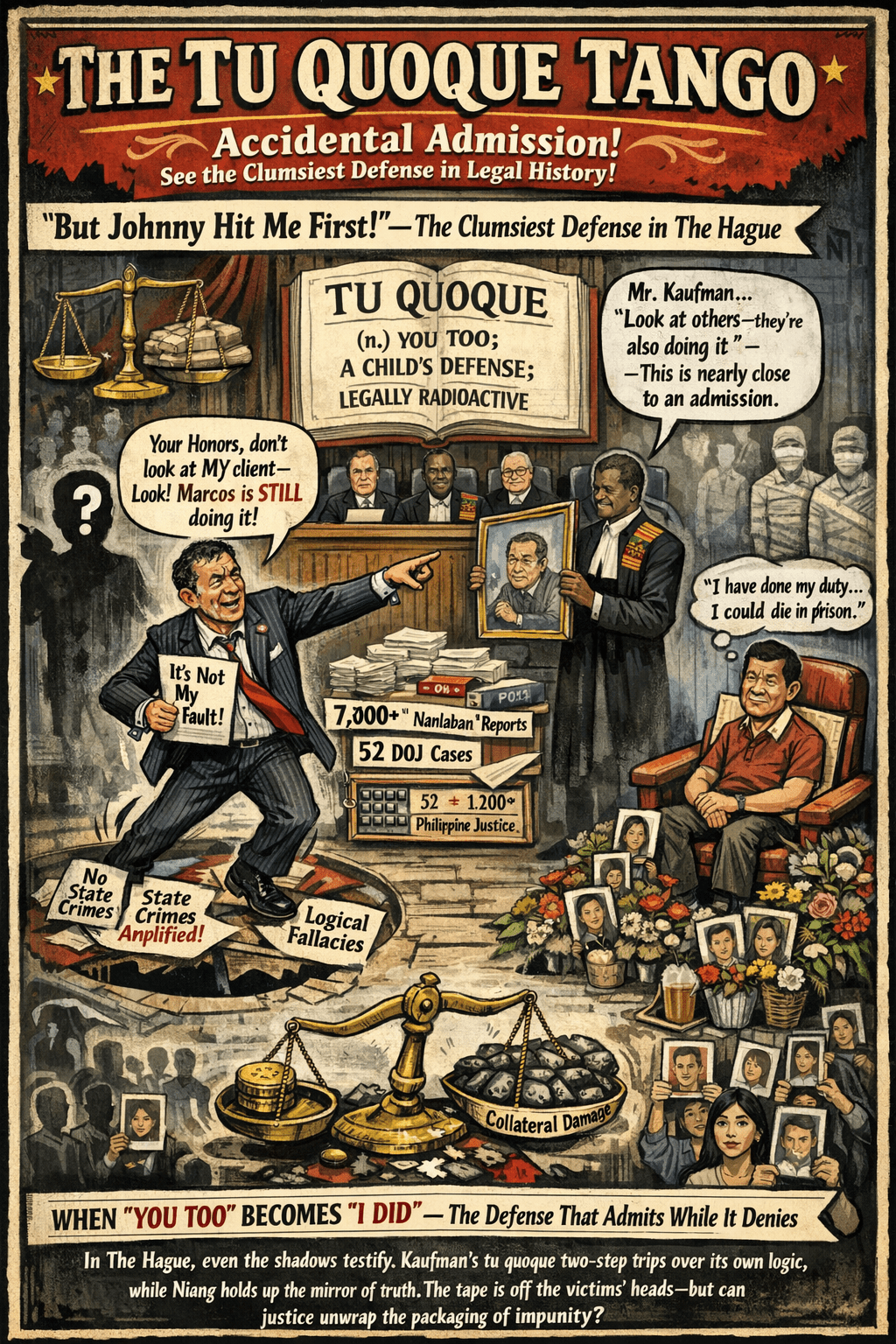

3. Defense Desperation: Duterte’s Last Stand?

Jurisdiction Jab: The Withdrawal Gambit

Duterte’s team will argue that the Philippines’ 2019 ICC exit nullifies jurisdiction, citing Article 127(1). However, Article 127(2) and Pangilinan v. Cayetano make it clear: pre-withdrawal crimes remain fair game. A sovereignty plea under the UN Charter (Article 2(7)) may sound principled, but the ICC’s foundational authority renders it moot.

Immunity Illusion: No Shield for Ex-Kings

Article 27 of the Rome Statute explicitly denies immunity to heads of state, and Estrada v. Desierto reinforces this domestically. The 1998 arrest of Augusto Pinochet in the UK set the precedent—ex-leaders are not untouchable. Duterte’s claims of immunity are legally baseless.

Complementarity Con: “We’ve Got This” Bluff

Article 17 allows the ICC to defer to national courts if they genuinely prosecute the crimes. Duterte may point to Philippine investigations, but the ICC’s 2023 Appeals decision exposed these as shams. It’s a long shot with little chance of success.

Political Posturing: The West’s Puppet Play

Duterte will likely frame the ICC as a tool of Western imperialism—a rallying cry for his base but irrelevant in court. Article 21 ensures that legal proceedings are grounded in law, not geopolitics. It’s noise, not a legal strategy.

4. Stakeholder Storm: Who’s Caught in the Blast?

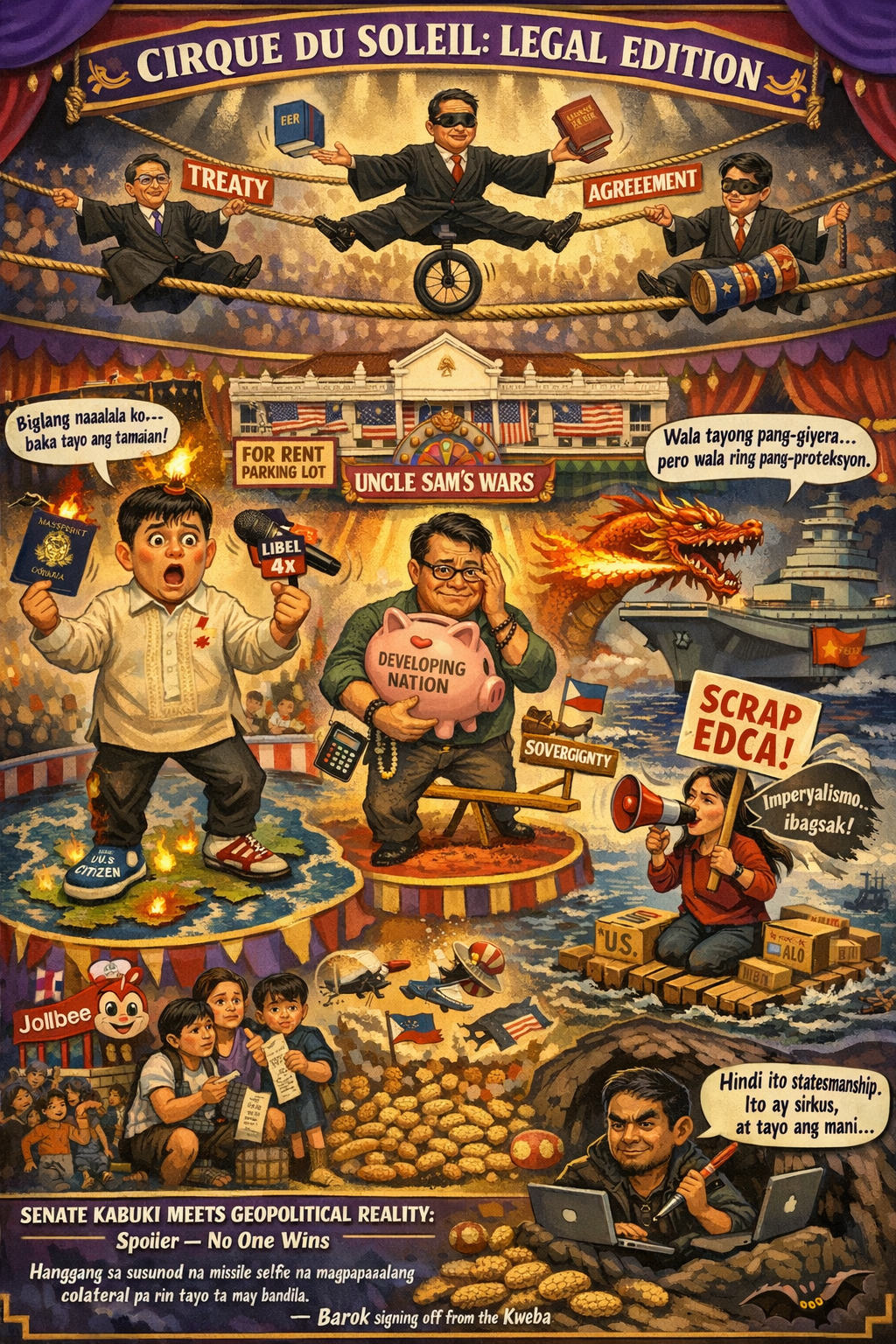

Marcos’ Tightrope: Duty vs. Drama

Marcos Jr. faces a delicate balancing act. RA 9851 and Pangilinan compel cooperation with the ICC, but stalling risks international backlash. Navigating the demands of law and Duterte’s loyalists is a high-wire act with no safety net.

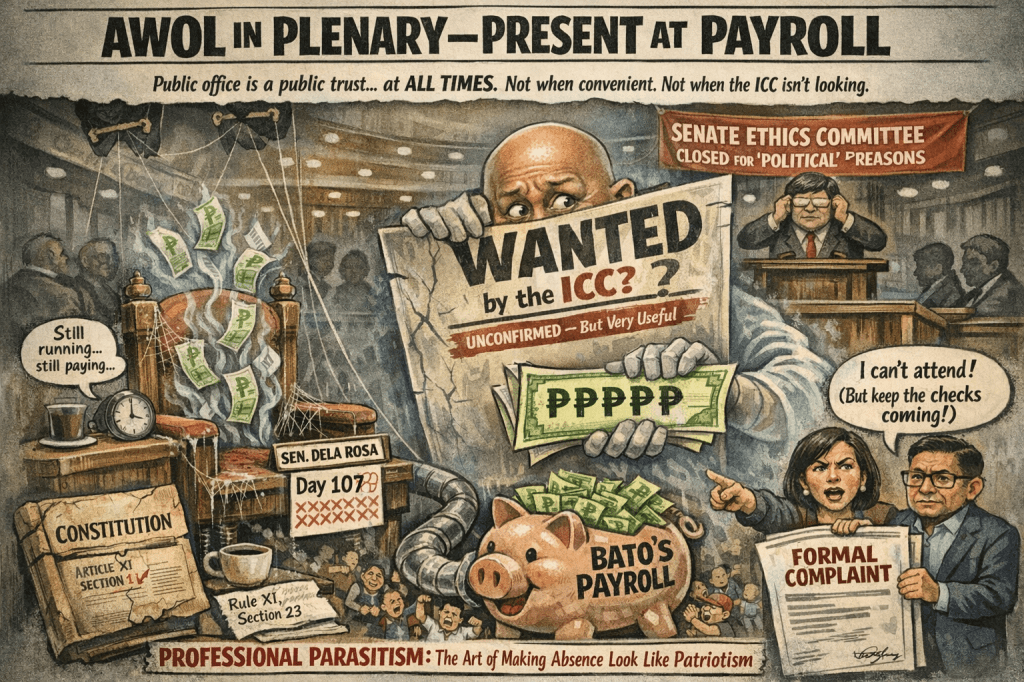

Cronies in Crosshairs: The Domino Risk

Articles 25 and 28(b) could ensnare former PNP officials and Davao allies—Bato dela Rosa is already sweating. If Duterte is the mastermind, they’re the enforcers, and the ICC loves a two-for-one deal.

Sovereignty Sting: A National Bruise

Foreign judges ruling on a Filipino icon is a bitter pill. RA 9851 traded sovereignty for international accountability long ago. Non-cooperation could strain relations with ICC member states, but economic interests often outweigh pride.

Victims’ Vengeance: A Voice at Last

Article 68(3) grants victims a platform—testimony, reparations, and more. The drug war’s bereaved finally have a chance at justice, turning 30,000 ghosts into a legal force.

The Big Picture: A Global Gut Check

Duterte’s arrest isn’t just a Philippine drama—it’s the ICC asserting its relevance in a world where figures like Putin and Netanyahu flout international law. For the global legal order, it’s a test of universal jurisdiction versus national sovereignty. For the Philippines, it’s a reckoning with a bloody past and a step toward accountability.

This saga will be a marathon—evidence, appeals, political maneuvering—but when justice is served, it’s a knockout. Stay tuned.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment