By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — March 14, 2025

THE Philippine Supreme Court is wading into a legal quagmire that’s equal parts procedural headache and political dynamite. On March 11, 2025, former President Rodrigo Duterte and Senator Ronald “Bato” Dela Rosa filed a 94-page certiorari and prohibition petition, seeking a temporary restraining order (TRO) to halt the government’s cooperation with the International Criminal Court (ICC). Their demands? Block arrest warrants tied to Duterte’s controversial “war on drugs,” impose a permanent injunction on ICC collaboration, and secure the release of anyone detained under ICC orders—primarily Duterte himself.

Chaos ensued: Duterte was arrested the same day by Philippine authorities under an ICC warrant and, by March 12 or 13, was surrendered to The Hague to face crimes against humanity charges. The Supreme Court, after a virtual hearing on March 13, denied the “immediate” TRO, citing no “clear and unmistakable right,” but left the door open for a future TRO while requiring respondents to submit comments within 10 days. Now, on March 14, with Duterte out of Manila’s jurisdiction, the mootness doctrine casts a long shadow. Is this petition dead on arrival, or can it claw its way back? Let’s dissect the legal thicket.

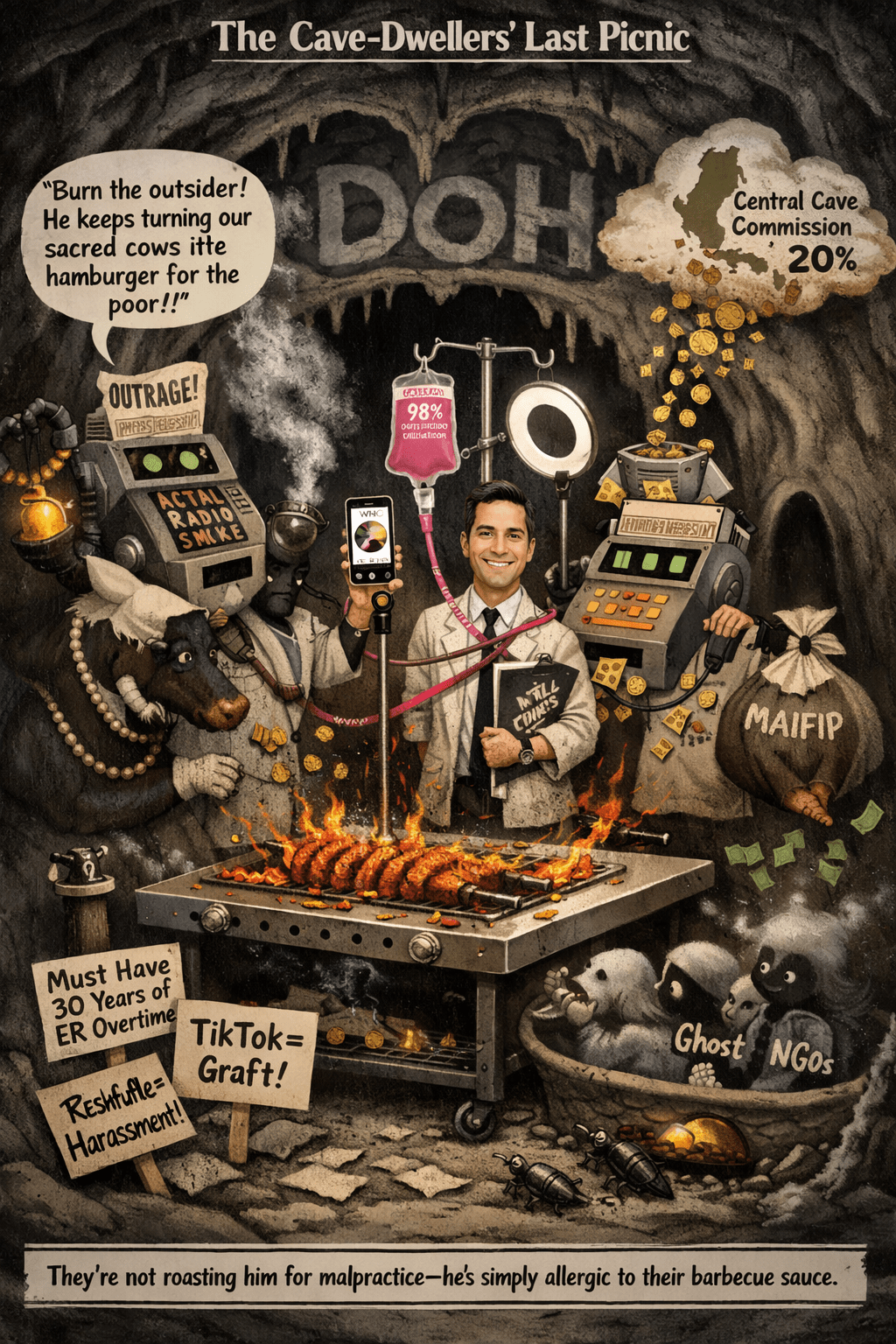

Kweba ng Katarungan’s Take: Duterte’s case is on life support, but Dela Rosa’s involvement and broader sovereignty questions might keep the defibrillators humming.

Mootness Unleashed: When Philippine Courts Say “Game Over”

Mootness Defined: The Supreme Court’s Kill Switch

In the Philippines, mootness isn’t just a legal buzzkill—it’s a judicial bouncer kicking pointless cases to the curb. The Supreme Court’s stance is clear: if supervening events extinguish the controversy, the case is dismissed. In Gunsi, Sr. v. Commissioners, Commission on Elections (G.R. No. 168792, Feb. 23, 2011), the Court ruled that a barangay official’s expired term mooted the case, rendering any ruling “of no practical value.” Similarly, in David v. Arroyo (G.R. No. 171396, May 3, 2006), a challenge to a state-of-emergency proclamation was dismissed after the proclamation lapsed—why rule on a storm that’s already passed?

Constitutional Muscle and Statutory Teeth

Mootness isn’t just tradition; it’s constitutional doctrine. Article VIII, Section 1 of the 1987 Constitution mandates that courts resolve only “actual controversies” with enforceable rights—once the dispute is over, the Court steps aside. Article VIII, Section 5(5) empowers the Court to address grave abuse of discretion, but only if there’s something left to address. Procedurally, Rule 65, Section 1 of the Rules of Court governs certiorari and prohibition, but it’s forward-looking—completed acts are beyond its reach. Rule 58, Section 4 (preliminary injunction) seals the deal: no TRO can revive a dead status quo.

Rules of Court: The Mootness Trap for Certiorari

Rule 65 focuses on stopping ongoing abuses, not remedying past actions. Once Duterte was arrested, the petition’s prospective relief evaporated. Rule 58’s TRO provisions are even stricter—if the controversy is resolved, injunctive relief is off the table. Here, mootness acts less like a doctrine and more like a guillotine.

Mootness Mauls Duterte: Where the Petition Bleeds Out

The Knockout Blows: Arrest and Exile

Duterte’s arrest on March 11 and subsequent transfer to The Hague on March 12-13 delivered a one-two punch to the petition. Its primary request—halting ICC cooperation on arrest warrants—is now irrelevant. The precedent in Province of North Cotabato v. GRP (G.R. No. 183591, Oct. 14, 2008) is clear: when a controversy dies mid-case, the Court dismisses it. Duterte is in ICC custody; Manila’s role is history.

Relief Roulette: What’s Dead, What’s Breathing?

Breaking down the petition’s requests:

- TRO and Injunction vs. Cooperation: Dead for Duterte. The arrest and transfer are complete; reversing them is impossible.

- Free the Captives: Dead on arrival for Duterte. David v. Arroyo makes it clear: rulings without practical effect are meaningless. ICC custody is beyond Manila’s control.

- Dela Rosa’s Future: Still alive. He hasn’t been arrested (yet), so enjoining future ICC actions remains a viable issue.

TRO Denial: A Mootness Accelerator?

The March 13 denial of an “immediate” TRO isn’t a lifeline—it’s a warning. The Court saw no urgent right pre-arrest, and post-arrest, the urgency is gone. Rule 58 emphasizes preserving the status quo, but with Duterte in The Hague, there’s nothing left to preserve. The 10-day comment window (due March 23) is more autopsy than surgery.

Mootness Busters: Can Exceptions Resurrect This Corpse?

Repeat Offender: Capable of Repetition, Evading Review

In Sanlakas v. Executive Secretary (G.R. No. 159085, Feb. 3, 2004), the Court kept a dead rebellion case alive because the same act could recur, evading review. Dela Rosa’s potential ICC exposure fits this exception: government cooperation could happen again, outpacing TROs. For Duterte, however, this exception is a coffin nail.

Big Deal Alert: Transcendental Importance

In Chavez v. Public Estates Authority (G.R. No. 133250, July 9, 2002), the Court addressed a moot case due to its high public significance. Duterte’s petition raises a constitutional bombshell: does ICC jurisdiction persist after the Philippines’ 2019 withdrawal from the Rome Statute (Article II, Section 2)? With Dela Rosa still at risk, the Court might weigh in under Article VIII, Section 5(1). Kweba ng Katarungan predicts they’ll bite—judges love a sovereignty showdown.

Fake-Out Fail: Voluntary Cessation

If the government reversed course mid-case, claiming mootness, David v. Arroyo would reject the argument. But here, cooperation is complete—Duterte is in The Hague. No cessation trickery to dodge.

Fight or Flight: Strategic Moves for the Petitioners

Pivot or Perish: Reframing the Fight

Dela Rosa is the golden ticket. Focus on his risk, abandon Duterte’s lost cause, and use Rule 65 to block future ICC actions. Alternatively, recast the petition as a declaratory relief bid under Article VIII, Section 5(1)—seeking a ruling on ICC jurisdiction that could set a lasting precedent.

Plan B: Scraping the Remedy Barrel

Duterte’s options are bleak. Habeas corpus (Rule 102) might have worked pre-Hague, but now it’s the ICC’s game. A misconduct complaint against officials for cooperating could stir the pot, but it’s a long shot. Internationally, contesting the arrest at the ICC is unlikely to succeed.

Constitutional Cannon: Firing at Mootness

Invoke Article II, Section 7 (protecting life) and Article III, Section 1 (due process), arguing that the arrest violated sovereignty. Cite Bayan Muna v. Romulo (G.R. No. 159618, Feb. 1, 2011) to claim executive overreach in foreign agreements. It’s a stretch, but it might spark judicial interest.

Power Plays: Judicial Restraint vs. Constitutional Swagger

This case walks a separation-of-powers tightrope. Dismissing it as moot respects executive action and judicial restraint—why rule on a done deal? But delving into Dela Rosa’s situation or ICC jurisdiction could ignite a turf war with Marcos Jr.’s administration. Article VIII, Section 1’s checks-and-balances framework gives the Court room to act, if it dares. Kweba ng Katarungan’prediction: they’ll flex, but not overreach.

Crystal Ball: Mootness Wins, But the Show Goes On

Here’s the verdict: Duterte’s arrest and transfer pleas are 85% dead—Gunsi, Sr. and David v. Arroyo bury them. TRO and release hopes? Extinguished. But Dela Rosa and the ICC sovereignty debate have a 60% chance of survival under Sanlakas or Chavez. Expect a split decision by early April—mootness for Duterte, pontification for the rest. The Supreme Court isn’t done grandstanding yet.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

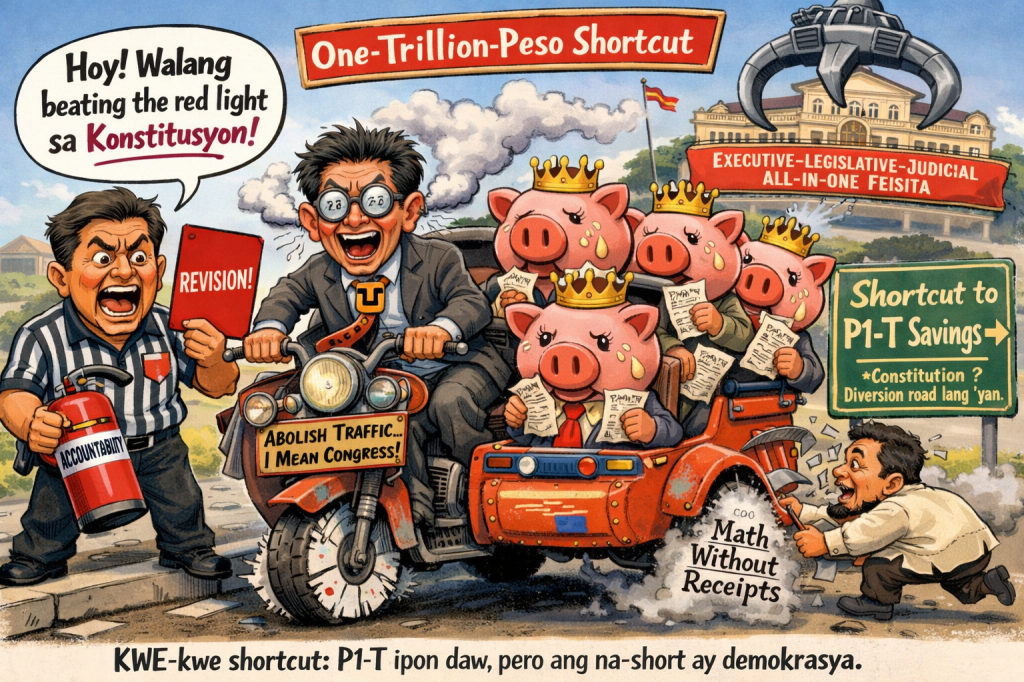

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment