By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — March 15, 2025

Introduction: A Legal Thriller Unfolds

Rodrigo Duterte’s arrest on March 11, 2025, wasn’t just a legal maneuver—it was a masterstroke of political theater. Handcuffed and flanked by a thousand police officers, the former Philippine president transformed his surrender into a high-stakes chess game, outmaneuvering his enemies in plain sight. According to “Did Rody outsmart the gov’t?” (ABOGADO.COM.PH, March 13, 2025), legal observers speculate that Duterte’s quiet compliance was a trap, designed to expose the Marcos administration’s procedural missteps and derail the ICC case under Article 59(3) of the Rome Statute.

It’s a narrative dripping with bravado and intrigue, but does it stand up to a legal stress test? Let’s dig into the facts, shred the arguments, and see if this is a masterstroke or a mirage.

Factual Flashpoint: The Arrest That Ignited a Firestorm

The timeline is crisp:

- Duterte touched down at Manila’s Ninoy Aquino International Airport from Hong Kong at 8 PM on March 11, 2025.

- He was nabbed by the Philippine National Police (PNP) on an Interpol red notice tied to an ICC warrant.

- By midnight, he was jetting to The Hague.

Notably, no Philippine judge saw him first. The ICC targets his 2016-2019 drug war, alleging crimes against humanity under Article 7 of the Rome Statute—jurisdiction upheld despite the Philippines’ exit on March 17, 2019 (Rome Statute, Art. 127(1)).

At 79, frail and flanked by 1,000 PNP officers, Duterte didn’t resist—a pivot from his earlier “I’ll never answer them” bravado. Marcos calls it Interpol duty, not ICC groveling. Now, legal hawks cry foul, and the “trap” buzz begins.

Legal Showdown: Where the Rubber Meets the Road

Fact-Checking Frenzy: Truth, Plausibility, or Hot Air?

The opinion piece scores points on facts:

- Duterte’s transfer dodged local courts.

- Article 59(3) of the Rome Statute demands a “judicial authority in the custodial State” review arrests (Rome Statute, Art. 59(3)).

- The PNP’s reliance on executive stand-ins—Prosecutor General and Justice Undersecretary—doesn’t cut it under Philippine judicial norms (1987 Phil. Const., Art. VIII, § 1) or ICC precedent (e.g., Prosecutor v. Katanga, ICC-01/04-01/07, 2008).

Research backs the timeline: arrest to takeoff in four hours.

But it leaps to shaky ground:

- Duterte’s “I’ll accept it” quip in Hong Kong and silence during arrest hint at strategy, yet no filings or insider leaks (e.g., from counsel Harry Roque) prove a trap.

- His health—chronic illness at 79—and overwhelming PNP muscle offer simpler explanations.

- The “fruit of the poisonous tree” tag is a stretch—it’s a U.S. Fourth Amendment gem (e.g., Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471 (1963)), not ICC canon, and procedural glitches rarely kill cases outright (see Bemba, ICC-01/05-01/08, 2018).

Reasoning Rumble: Brilliant or Brittle?

The piece’s legal hook—that skipping Article 59(3) poisons the case—packs punch. The Rome Statute’s text is unambiguous: arrestees get a shot at interim release via a domestic court (Rome Statute, Art. 59(3)). Philippine law echoes this—RA 9851 (§ 7) and Revised Rules of Court (Rule 112, § 6) mandate judicial warrants for extradition-like moves. Bypassing this hands Duterte’s team a weapon: challenge custody under Article 60(2) or jurisdiction under Article 19(1) (Rome Statute, Arts. 60(2), 19(1)).

But the argument trips over itself:

- The Philippines’ 2019 ICC withdrawal (effective March 17, 2019, per Rome Statute, Art. 127(1)) clouds Article 59’s grip—does it bind a non-member cooperating via Interpol?

- Scholars brawl: some say yes, citing customary law; others say no, pointing to withdrawal’s clean break.

- Interpol’s red notice dodges treaty rigor—its Constitution (Art. 3) doesn’t demand judicial review unless local law does, and Marcos leaned on executive fiat (Exec. Order No. 163, s. 1987).

- Plus, the ICC can shrug off such slips if custody sticks (Prosecutor v. Lubanga, ICC-01/04-01/06, 2006).

The “trap” bets on a knockout the ICC might sidestep.

Dueling Takes: Who’s Got the Better Argument?

Duterte’s Corner: Sovereignty’s Last Stand

Team Duterte—think Sara Duterte’s “sovereignty sellout” jab—sees an illegal handover. A non-ICC Philippines should’ve flexed local courts under Article 59(3) and complementarity (Rome Statute, Art. 17(1)(a)). They’d argue domestic probes (however anemic—four convictions) block ICC meddling. A procedural violation could spring him via Article 60(2).

Justice Over Jargon: ICC and Marcos in Focus

The ICC and Marcos retort: jurisdiction over pre-2019 crimes is locked (Rome Statute, Art. 127(1); ICC Appeals Chamber, July 17, 2023). Interpol’s red notice reflects global norms (INTERPOL Rules, Art. 83), not ICC bowing, and Article 19 lets the court self-correct procedural noise (Katanga, ICC-01/04-01/07, 2008). Rights groups cheer—20,000+ drug war dead demand reckoning, not technical outs.

Fence-Sitters: The Muddy Middle

Realists see a mess. Withdrawal blurs Article 59’s teeth, and Interpol’s ad hoc vibe skirts treaty rules. The ICC might rap the process but keep Duterte, like Kenya’s 2011 ICC tango—cooperation without full compliance.

Fallout Forecast: What’s at Stake?

Legal Landmines

A solid Article 59(3) play could snag Duterte interim release (ICC Rules of Procedure, Regulation 51) or stall proceedings. Dismissal’s a long shot—Bemba (ICC-01/05-01/08, 2018) shows substance trumps slip-ups. His health, though, could derail faster—think Milošević’s 2006 exit (ICC-01/99-37, 2006).

Political Powder Keg

Marcos faces a nationalist uprising—Duterte’s base rages (X chatter calls it a “boomerang”). A freed Duterte could turbocharge the Duterte-Marcos feud, with Sara eyeing 2028. The Supreme Court’s TRO dodge leaves habeas corpus as a wildcard.

Diplomatic Dice Roll

The ICC’s street cred hangs in balance: bagging Duterte boosts it, but a flub could fuel skeptics (e.g., U.S. sanctions talk). Philippines-US ties, already ICC-tense, watch Marcos—will he flirt with Rome Statute reentry?

Battle Plan: Smart Moves for All Sides

Duterte’s Gambit

- Hammer Article 59(3)—file for release under Article 60(2) (Rome Statute, Art. 60(2)), citing rights breaches.

- Stack a health plea (ICC Rules, Regulation 103); it’s a surer exit than jurisdiction wars.

Marcos’ Counter

- Backfill Interpol compliance—lodge affidavits with the ICC proving “substantial compliance” (e.g., DOJ oversight).

- Own the narrative to douse sovereignty flames.

ICC’s Call

- Nod to the breach but lock custody under Article 19 (Rome Statute, Art. 19(1)). Katanga (ICC-01/04-01/07, 2008) says evidence rules, not process glitches.

Philippine Courts

- Rush habeas corpus (1987 Phil. Const., Art. III, § 15) to define local duty—silence screams cowardice.

Final Verdict: Trap or Tightrope?

Duterte a legal Houdini? Doubtful—but Marcos and the PNP tossed him a lifeline with that Article 59(3) fumble. It’s a real flaw—legally dicey, politically combustible—yet the ICC’s grit and Interpol’s shadow likely keep him caged.

This isn’t a sprung trap; it’s a high-wire act. Duterte’s odds ride on health, evidence, and ICC pragmatism, not just a procedural jab. For now, it’s less “checkmate” and more “stay tuned.” Pass the popcorn—this one’s got legs.

Disclaimer: This is analysis, not legal advice—call a lawyer if you’re in the hot seat.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

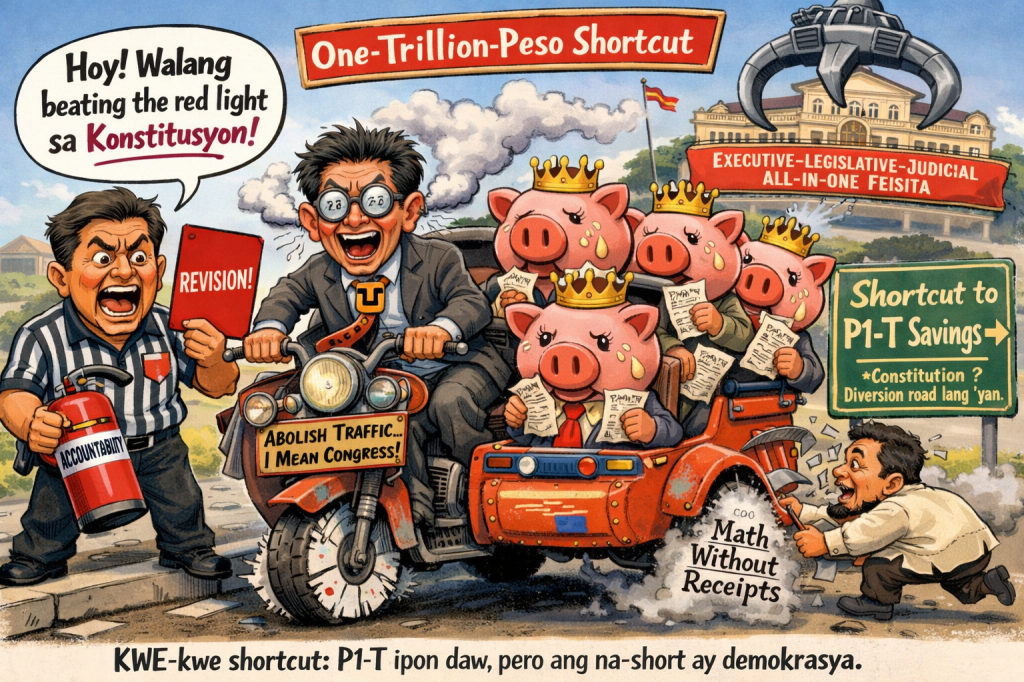

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

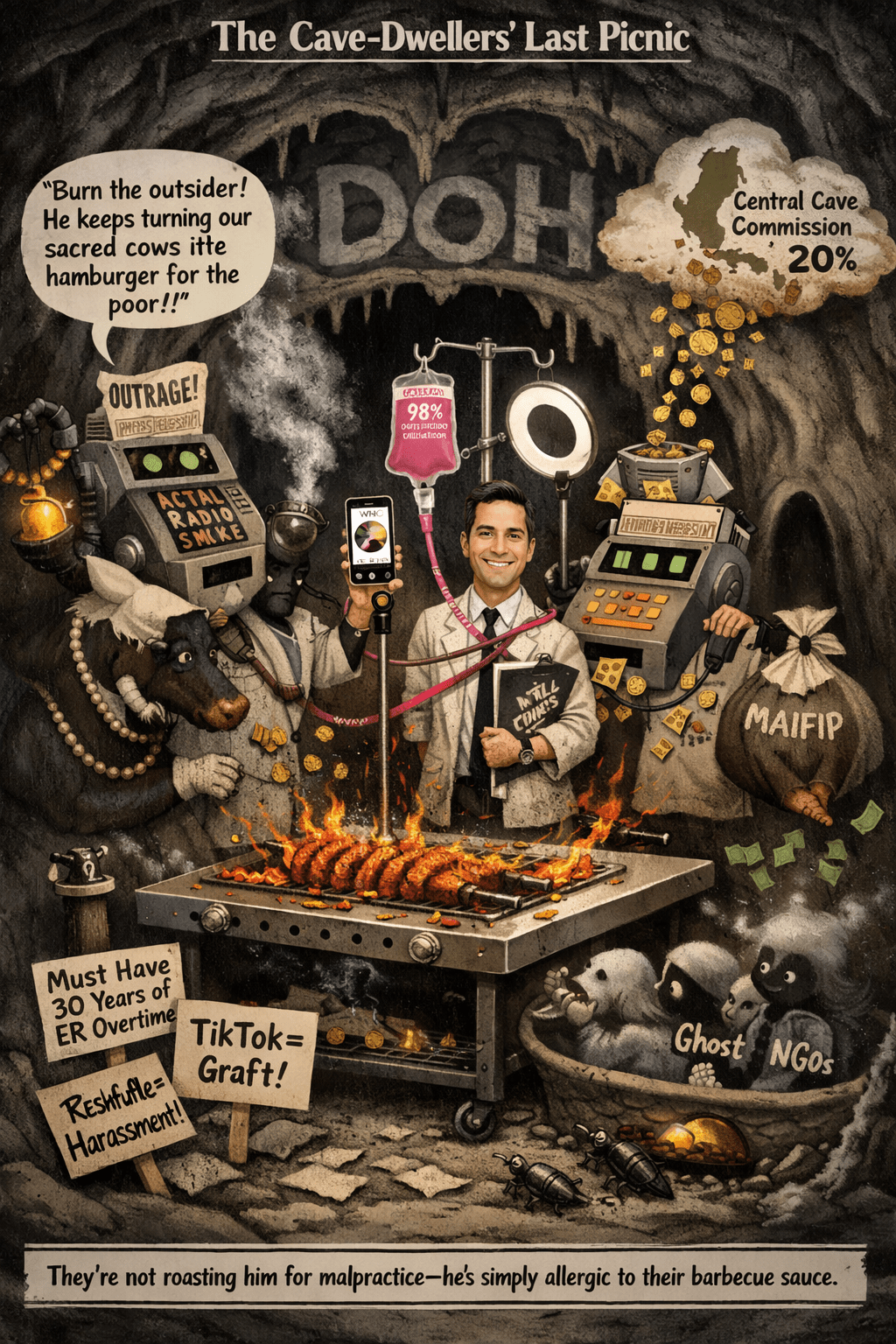

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment