By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — March 16, 2025

THE arrest of former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for alleged crimes against humanity during his brutal “war on drugs” has ignited a legal firestorm. This case pits the ICC’s global jurisdiction against Philippine sovereignty, raising explosive questions: Was due process violated? Does the ICC retain authority after the Philippines withdrew from the Rome Statute? This analysis cuts through the jurisdictional chaos, examines procedural clashes between the ICC, Interpol, and Philippine legal frameworks, and highlights the shaky legal grounds of Duterte’s extradition to The Hague. Buckle up for a wild ride through the intersection of law and power.

Jurisdiction Jumble: Who’s Really Calling the Shots?

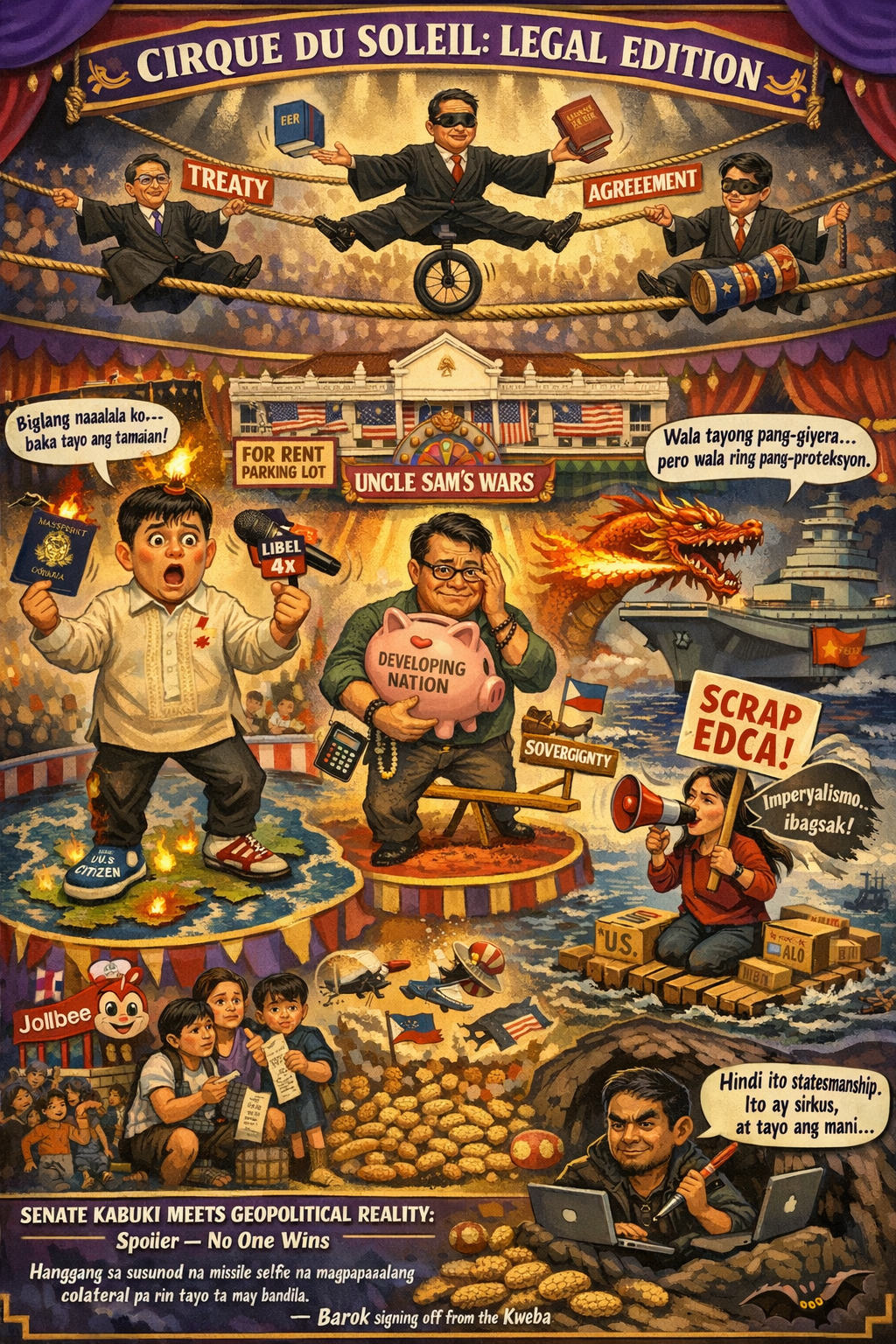

The ICC’s authority over Duterte hinges on Article 127(2) of the Rome Statute, which allows investigations initiated before a country’s withdrawal to continue. The Philippines exited the ICC on March 17, 2019, but Duterte’s alleged crimes—spanning 2011 to 2019—fall within the court’s temporal jurisdiction, as confirmed by the March 7, 2025, arrest warrant. Duterte’s legal team argues that the ICC lost jurisdiction upon the Philippines’ withdrawal, citing The Prosecutor v. Joseph Kony (ICC-02/04-01/05), where the court maintained jurisdiction over pre-withdrawal crimes. The Philippines’ cooperation with Interpol further complicates matters, as it blurs the lines between direct ICC authority and treaty-based assistance. While Pangilinan v. Cayetano (G.R. No. 238875, 2021) acknowledges residual cooperation, the legality of the arrest remains a cliffhanger.

Procedure Smackdown: ICC, Interpol, and Manila Face Off

Rome Statute: Arrest or Bust?

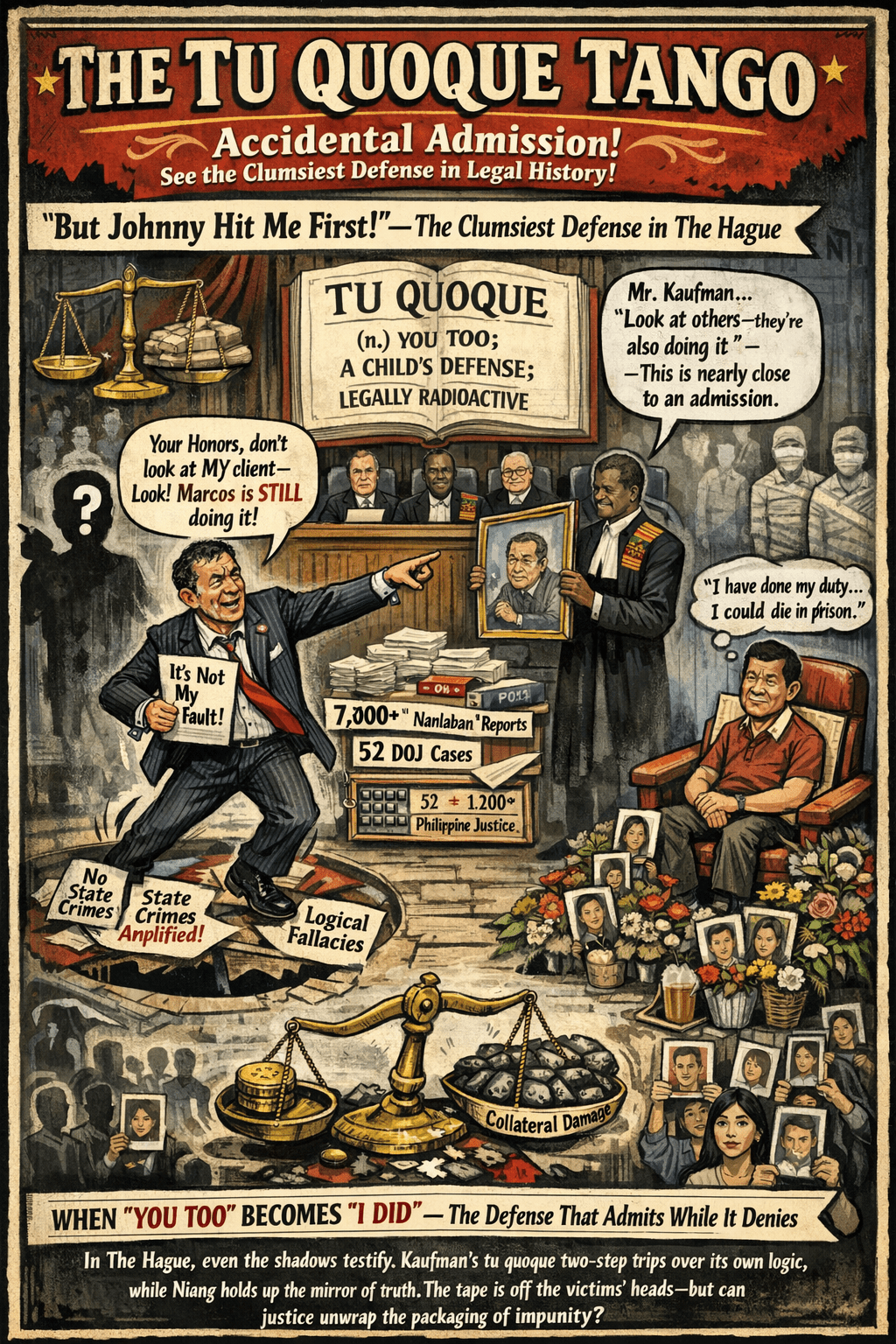

Under Article 58, the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber issues arrest warrants based on “reasonable grounds”—a standard met in Duterte’s case, given his alleged involvement in death squad and police killings. Article 59 requires the custodial state to conduct a judicial review to ensure the suspect’s rights are protected. However, Manila bypassed this step before extraditing Duterte. Similar procedural oversights were overlooked in The Prosecutor v. Dominic Ongwen (ICC-01/04-02/15), where custody took precedence over local due process. While due process was compromised, it wasn’t entirely disregarded.

Interpol: Global Cop or Rights Watchdog?

Article 2 of Interpol’s Constitution binds the organization to respect local laws, yet the Red Notice system—used to facilitate Duterte’s arrest—operated smoothly. The Sergey Magnitsky case (Interpol, 2019) demonstrates Interpol’s ability to reject politically motivated notices, but Duterte’s Red Notice remains intact. His attempt to evade fingerprinting under the Rules on Processing Data (2009) is a minor hurdle, not a dealbreaker.

Philippine Law: Constitutional Casualty?

The 1987 Philippine Constitution’s Article III, Section 1 guarantees due process, with Section 2 and Rule 112 requiring judicial probable cause before arrest. Duterte was neither afforded a preliminary investigation nor a judicial review before his extradition. People v. Enrile (G.R. No. 213847, 2015) underscores the necessity of judicial review, making its absence in Duterte’s case a glaring red flag. While RA 9851 (2009) addresses national jurisdiction, it lacks clarity on extradition, creating legal quicksand.

Global Rules Roulette: Custody Chaos and No-Show Trials

The ICC’s prohibition of trials in absentia—per Article 63(1) and reinforced by former Judge Pangalangan—makes Duterte’s physical presence mandatory. This contrasts with the Philippines’ People v. Estrada (G.R. No. 164368, 2006), where fugitives can be tried post-arraignment. International law often prioritizes custody over the means of apprehension, as seen in US v. Álvarez-Machaín (505 U.S. 655, 1992) and the Adolf Eichmann case (Israel, 1961). While Duterte’s arrest follows this precedent, it raises questions about the legitimacy of the process.

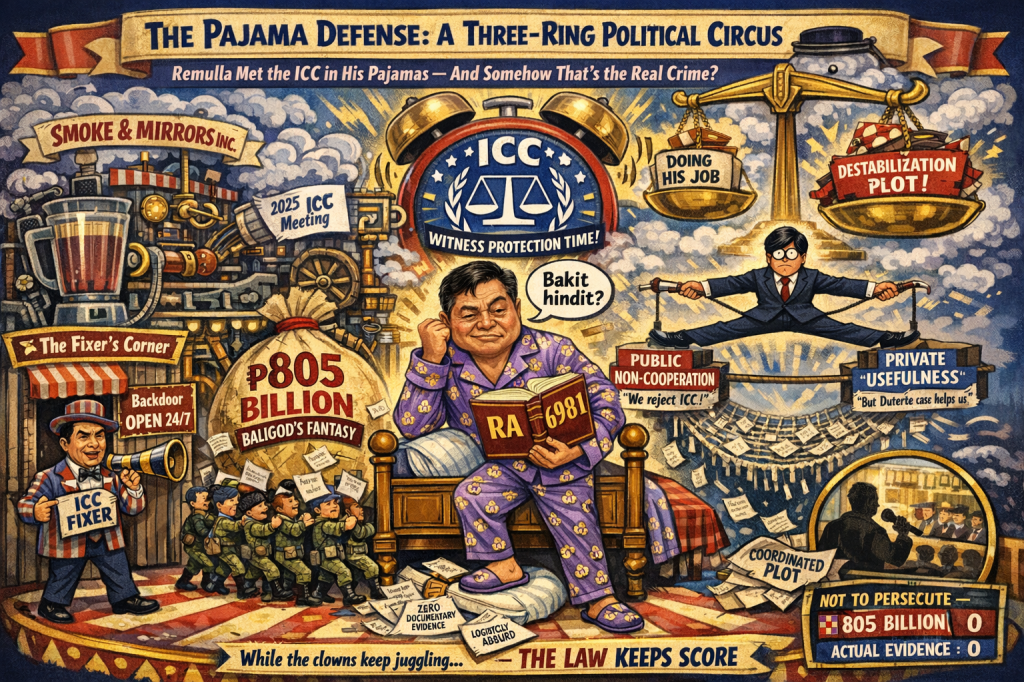

Hague Handover Hullabaloo: Legal Loopholes or Kidnapping Cover?

Duterte’s arrest on March 11, 2025, and subsequent transfer to the Netherlands under ICC custody relied on the ICC’s Headquarters Agreement (2007). Former Judge Pangalangan’s observation that acquitted detainees could become “illegal aliens” highlights the practical complexities. However, bypassing Article 59(2)’s judicial review in Manila creates a significant legal loophole. While the Ongwen case may excuse such oversights, Duterte’s claim of being “kidnapped” could damage the ICC’s public image.

Battle Plan: What’s Next for the Legal Gladiators

- Duterte’s Team: Challenge the ICC’s jurisdiction under Article 19, citing procedural flaws under Article 59 and leveraging Pangilinan to contest post-withdrawal arrests.

- Philippine Government: Amend RA 9851 to clarify extradition procedures and scrutinize Interpol’s role in treaty-based arrests.

- ICC Prosecutors: Ensure compliance with Article 59, even retroactively, and assert temporal jurisdiction as in the Kony case.

- Watchdogs: Demand transparency in Interpol’s Red Notice system to dispel accusations of political persecution.

Final Verdict: Justice on a Tightrope

Duterte’s arrest by the ICC is a legal spectacle, showcasing the tension between international justice and domestic sovereignty. While the ICC and Interpol flex their enforcement muscles, the bypass of Philippine due process risks a sovereignty backlash. Historical precedents like Eichmann and Álvarez-Machaín suggest that custody often outweighs procedural irregularities, but Manila’s disregard for judicial review could undermine the legitimacy of the process. For legal observers, this case represents global justice’s high-wire act: thrilling, flawed, and far from over.

Disclaimer: This analysis is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Consult a qualified attorney for legal guidance.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment