By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — March 18, 2025

MARY Ann Domingo’s voice still shakes when she talks about that night. ‘They just came in,’ she told me, her hands clutching a faded photo of her family. ‘No warning, no explanation.’ It was 2016, and police had stormed her home in Caloocan City, dragging her husband, Luis Bonifacio, 45, and son, Gabriel, 19, into the night. Hours later, their bodies were found, riddled with bullets—victims of the Philippines’ so-called ‘war on drugs.’ ‘They took my whole world,’ she said, tears staining the photo. Her story is one of thousands, a chilling reminder of the brutality unleashed under former President Rodrigo Duterte. Now, as Duterte faces charges at the International Criminal Court (ICC), Mary Ann’s loss—and the nation’s—demands a reckoning.

The “one time, big time” (OTBT) police operations, like the one that claimed Kian delos Santos, a 17-year-old shot dead in Caloocan in 2017, are at the heart of the ICC case against Duterte. These raids, concentrated in places like Bulacan and Caloocan from 2017 to 2018, were billed as decisive strikes against drug syndicates. Instead, they became emblems of a policy that Human Rights Watch estimates left over 12,000 dead—possibly as many as 30,000—most of them poor, urban men gunned down without trial. In just 24 hours in August 2017, Bulacan police killed 32 people, a massacre Duterte praised as “maganda ‘yun” (“that’s good”). The numbers are staggering, but it’s the human toll—families like Mary Ann’s, shattered by grief and stigma—that reveals the true cost.

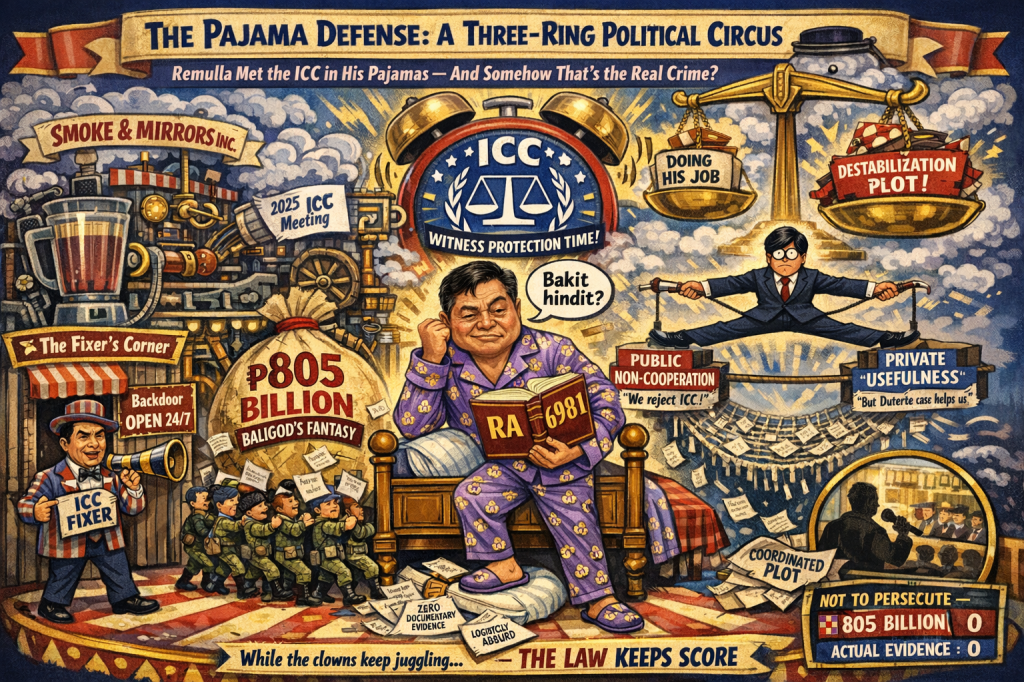

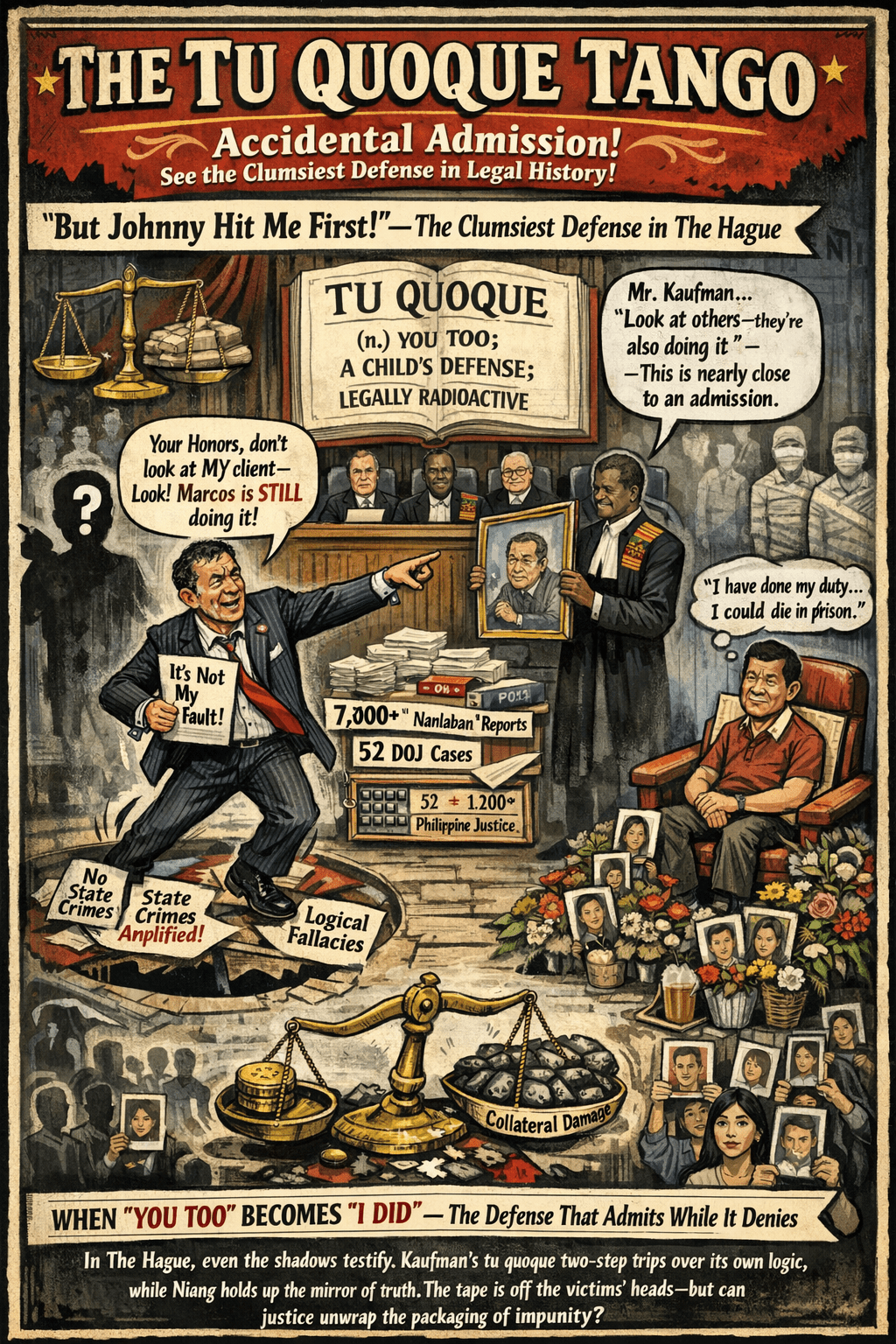

The ICC alleges Duterte was an “indirect co-perpetrator” in 43 killings, including eight from OTBT operations, linking them to a broader pattern of crimes against humanity. Prosecutor Karim Khan’s case ties these deaths to the Davao Death Squad, a vigilante group Duterte allegedly oversaw as mayor, and the nationwide drug war he unleashed as president. The legal stakes are high: though the Philippines withdrew from the ICC in 2019, the court retains jurisdiction over crimes committed during its membership, up to March 16, 2019. Duterte’s arrest on March 11, 2025, after landing in Manila from Hong Kong, marks a historic step. Yet, his supporters decry it as foreign overreach, while his lawyers may challenge the ICC’s authority—a debate that could drag on, testing the court’s reach.

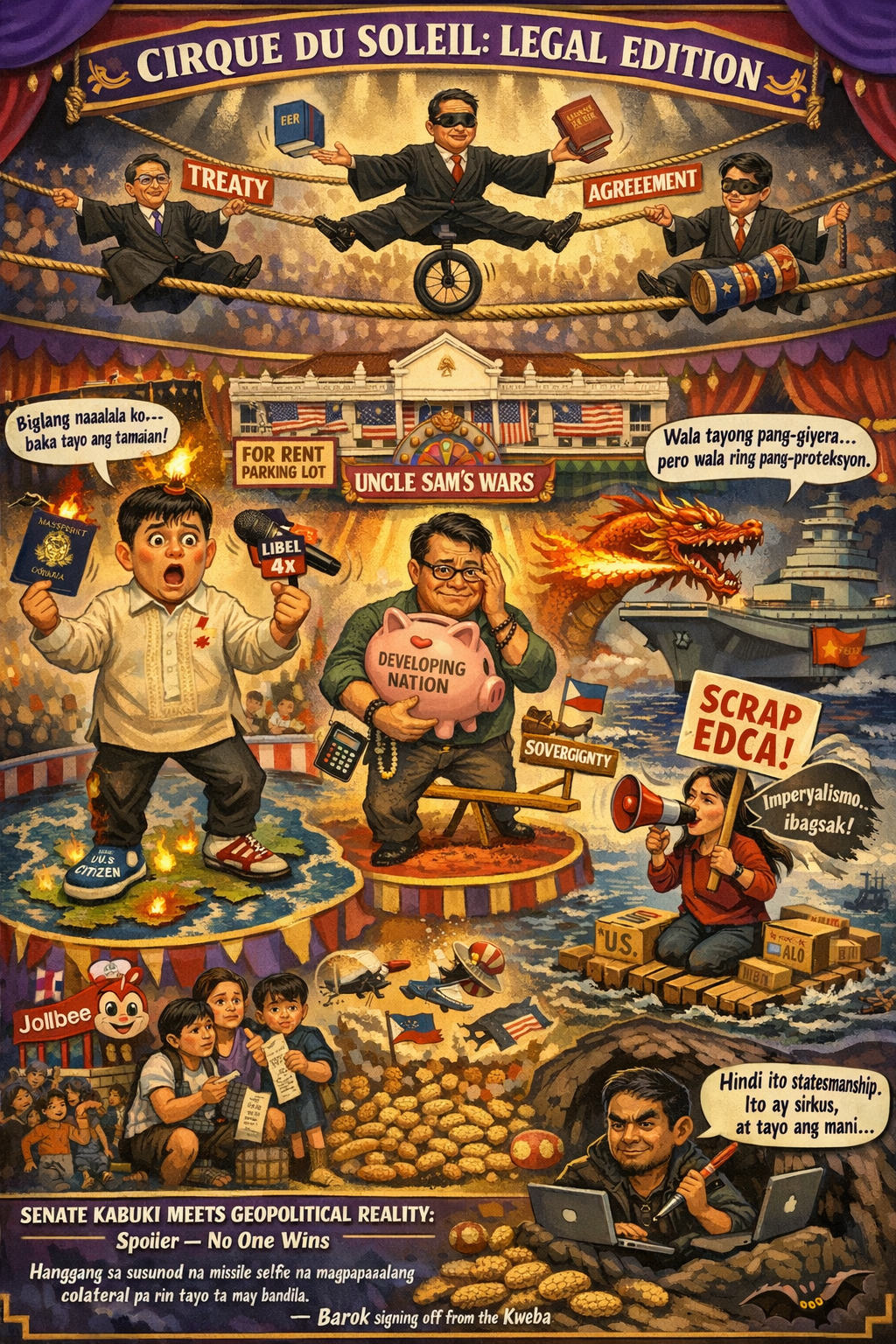

Politically, this case is a minefield. Duterte’s drug war, launched in 2016, won him fierce loyalty among Filipinos tired of crime, with approval ratings once soaring to 77%, per Social Weather Stations. His profanity-laced bravado—“I’d kill you,” he warned drug pushers—resonated in a nation desperate for order. But that popularity masked a darker reality: a campaign critics say doubled as a tool to silence dissent and consolidate power. The Marcos government’s reluctant cooperation with the ICC, shifting only after a rift with Duterte’s daughter, Vice President Sara Duterte, hints at a political calculus more about clan rivalry than justice. Internationally, the case spotlight’s Washington’s muted response—once a vocal Duterte ally—raising questions about America’s commitment to human rights when strategic interests are at play.

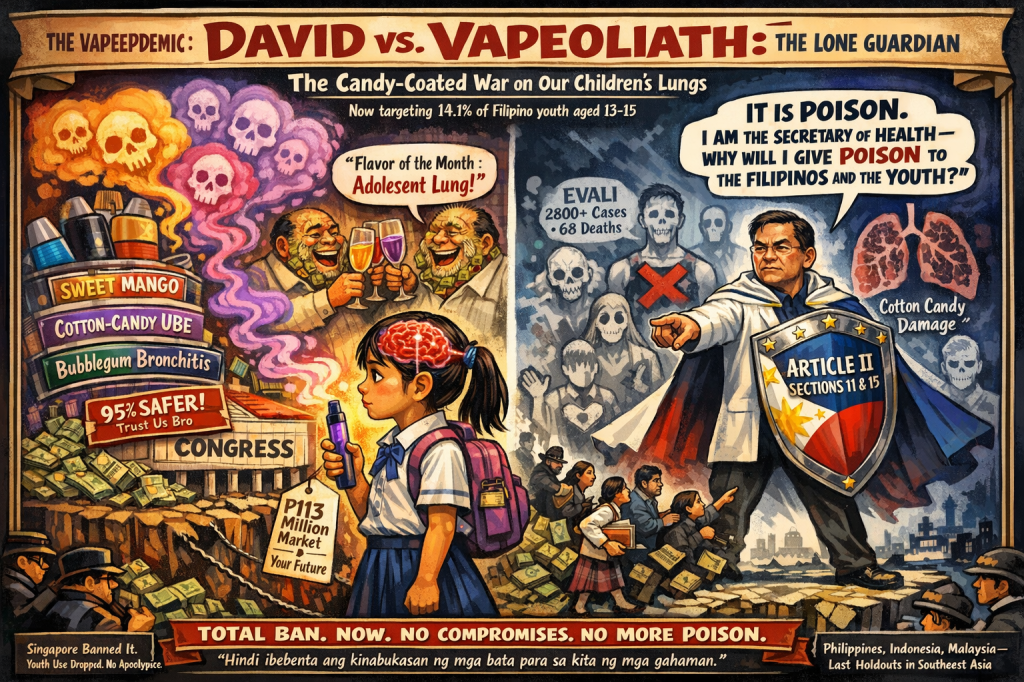

This isn’t just a Philippine story; it’s a cautionary tale of authoritarian drug policies gone awry. From Mexico’s cartel wars to Thailand’s 2003 drug crackdown, which killed over 2,800, we’ve seen this playbook: mass violence masquerading as law enforcement, with the poor bearing the brunt. Duterte’s approach, formalized by then-police chief Ronald “Bato” Dela Rosa’s Oplan Tokhang, turned police into executioners, often with vigilante help—Rappler found over 500 such killings in Bulacan alone from 2016 to 2017. The moral clarity here is stark: no one disputes the scourge of drugs, but slaughtering suspects, planting evidence, and orphaning children isn’t justice—it’s tyranny.

Yet, there’s nuance. Duterte’s defenders argue he tackled a real crisis—methamphetamine ravaged communities, and police claim the 6,200 official deaths were shootouts, not executions. Families like Mary Ann’s counter that their loved ones weren’t drug lords but breadwinners caught in a dragnet. The truth likely lies in between: a policy with some intent to curb crime, warped by unchecked power and impunity. Former ICC judge Raul Pangalangan notes that Duterte’s “indirect perpetrator” status doesn’t lessen his culpability—it’s the mastermind, not the triggerman, who designs the carnage.

The human cost is excruciatingly clear when you meet the survivors. Children of victims, Human Rights Watch reports, face bullying and poverty, their trauma ignored by a government offering no support. NGOs like Program Paghilom step in, but it’s a drop in the bucket. Economically, the drug war’s inefficiency is glaring—billions spent on raids could have funded rehabilitation or jobs programs, addressing poverty’s role in drug use. Portugal’s decriminalization model, cutting addiction rates through treatment, stands in sharp contrast.

So, what now? Justice for Mary Ann and thousands like her hinges on the ICC, but its path is fraught—only four local convictions, including Kian’s killers, show how rare accountability has been. Duterte’s trial could galvanize reform, but only if paired with practical steps. The Philippine government should rejoin the ICC, signaling a break from impunity, and launch a truth commission to document the war’s toll, offering reparations to victims. The international community—yes, including the U.S.—must pressure Manila with targeted sanctions on complicit officials while funding local NGOs to heal communities. Civil society, from Rappler’s fearless reporters to grassroots advocates, should amplify victims’ voices, pushing for drug policies rooted in dignity, not death.

I’ve seen too many places where power crushes the powerless under the guise of order. In Manila, the “one time, big time” ops were no aberration—they were the plan. Duterte, now 79 and defiant, told a Senate inquiry last year, “I did what I had to do.” But what he did was rob families of their futures. Justice won’t bring back Luis or Gabriel, but it can honor their memory—and remind us that human rights aren’t negotiable, even in the toughest fights. Let’s start there, for Mary Ann, for Kian, for a nation that deserves better.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment