By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — March 21, 2025

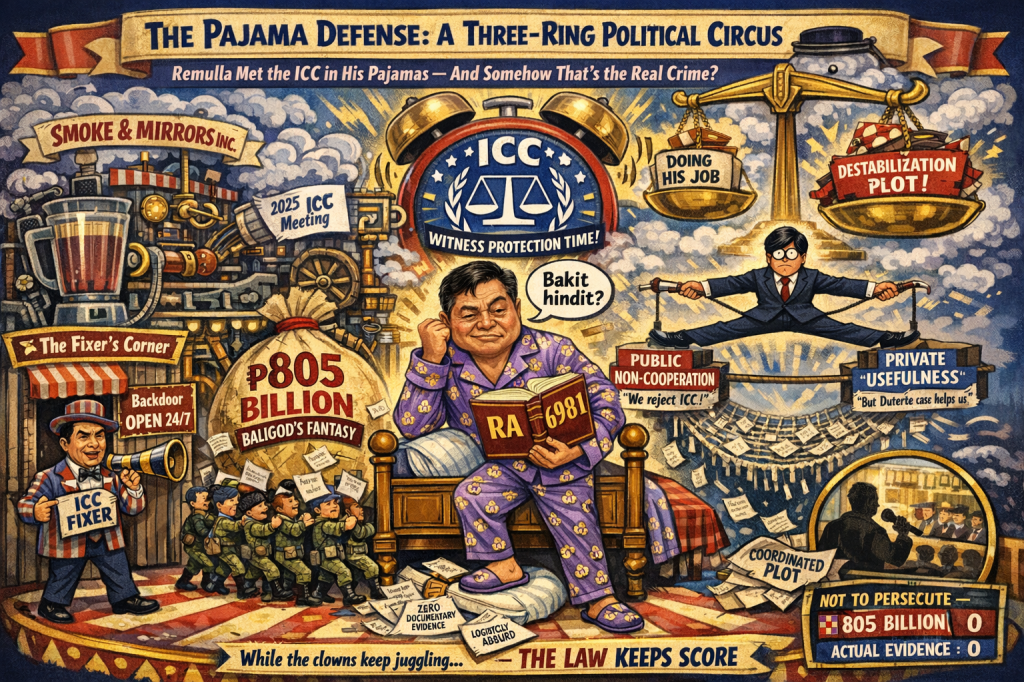

JUSTICE Secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla is walking a tightrope in the Philippines’ standoff with the ICC, trying to balance national pride with the messy realities of international law. His March 20, 2025, statements—paired with Senator Imee Marcos’s puzzled pushback—shine a spotlight on a legal and political puzzle that’s tough to unravel. The news report from Manila captures Remulla wrestling with a thorny issue, and while he’s not wrong on some points, the full picture is trickier than he lets on. Here’s a deep dive into the legal tangle and political storm, plus a few ideas to find solid ground.

1. Legal Hot Seat: Jurisdiction, Withdrawal, and Interpol’s Curveball

ICC’s Reach: Remulla’s Point Has Legs—Up to a Point

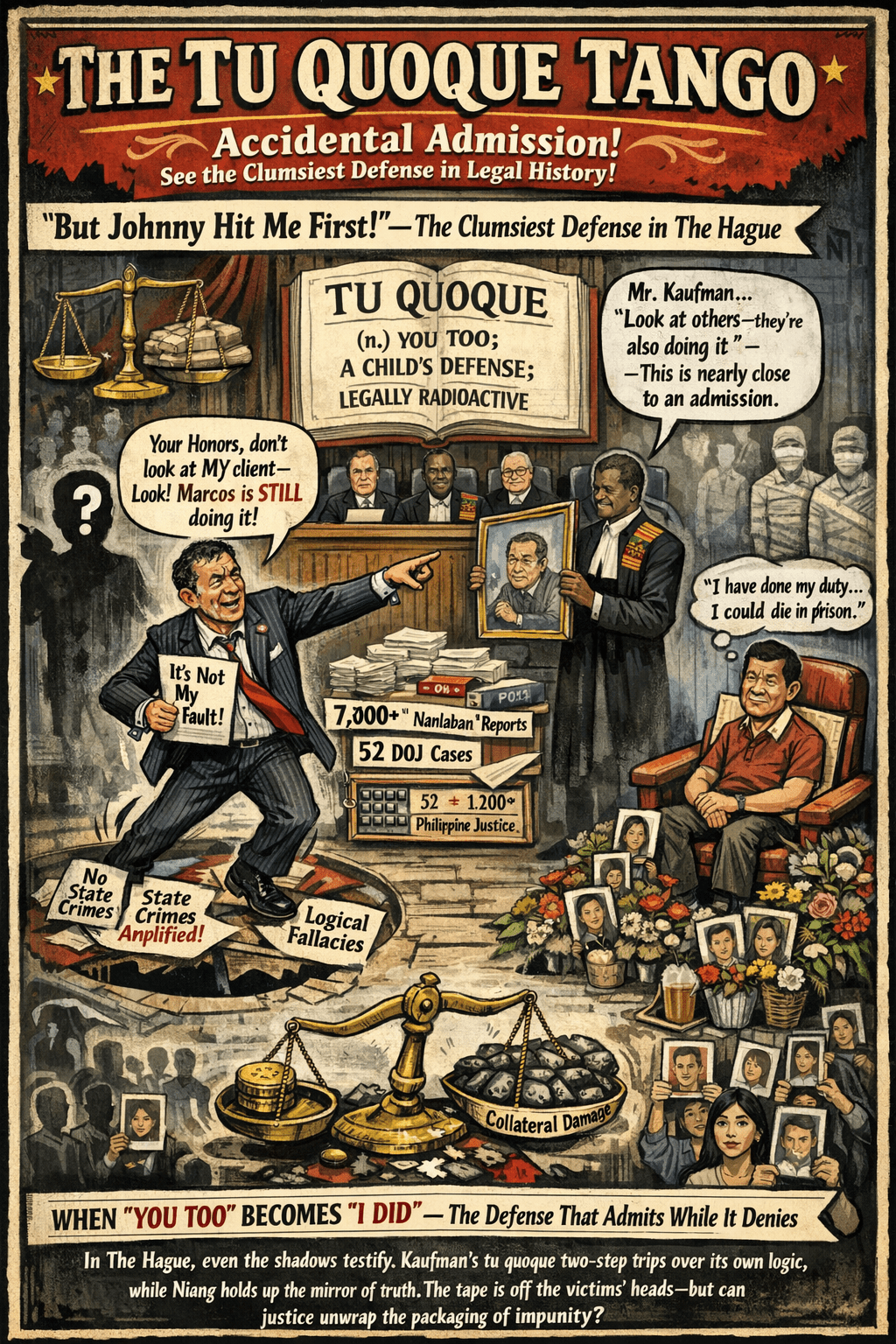

Remulla’s take—that the ICC can’t touch the Philippines as a state but can go after individuals—is straight from the Rome Statute’s playbook. Article 25(1) says it plain: “The Court shall have jurisdiction over natural persons pursuant to this Statute.” He’s right that states don’t face trial; people do. Where it gets dicey is his claim that the Philippines is off the hook for cooperation. Article 127(2) throws a wrench in that, noting that withdrawal (effective March 17, 2019) doesn’t erase duties tied to pre-exit investigations—like the ICC’s drug war probe, kicked off in 2021 for crimes from 2011 to 2019. Duterte’s March 11, 2025, arrest fits that timeline, suggesting Remulla’s facing a tougher legal bind than he’s admitting. He’s not wrong on the basics, but the fine print matters.

Marcos’s “I’m perplexed” moment about ICC jurisdiction post-withdrawal is relatable—who wouldn’t be confused? Article 12(1) clarifies that crimes during membership (like Duterte’s drug war) stay in play. Remulla’s juggling a fair point with a complex reality, and it’s a tough gig.

Withdrawal Woes: The Supreme Court’s Shadow

The Supreme Court’s Pangilinan v. Cayetano (G.R. No. 238875, July 21, 2021) gives Remulla some breathing room but also a headache. It let Duterte’s 2018 withdrawal stand as a done deal, but the obiter—“Withdrawing from the Rome Statute does not discharge a state party from the obligations it has incurred as a member”—nods to Article 127(2). Justice Carpio’s been vocal that this keeps pre-2019 crimes alive for the ICC, and Remulla’s got to wrestle with that legacy. Saguisag v. Executive Secretary (G.R. No. 212426, January 12, 2016) backs the Executive’s treaty powers but hints that laws like RA 9851 keep international duties in the mix. Remulla’s not imagining the sovereignty angle—it’s real—but the past won’t let go that easy.

Interpol’s Sneaky Assist: Cooperation by Proxy?

Duterte’s arrest hints at an Interpol Red Notice, and that’s where Remulla’s “no cooperation” stance gets tricky. Article 2 of the Interpol Constitution pushes members like the Philippines (since 1950) to tackle big crimes, ICC warrants included. Article 3’s neutrality rule might spark debate, but murder as a crime against humanity isn’t politics—it’s law. Remulla’s saying Manila didn’t help the ICC directly, and maybe he’s technically right—Interpol could’ve been the middleman. Still, those cuffs on Duterte suggest some dots got connected, and Remulla’s navigating a blurry line between intent and outcome.

RA 9851: Remulla’s Ace—or Achilles’ Heel?

Remulla leans on RA 9851 to show the Philippines can stand tall, and he’s got a case—Section 4 tracks Article 7, covering drug war killings if they’re “widespread or systematic.” But Section 17 says authorities “may surrender or extradite” to an international court “in the interest of justice” if someone else (like the ICC) is already digging. With no Duterte prosecution at home and the ICC in gear, Remulla’s self-sufficiency pitch hits a snag—Section 17 and the complementarity principle (Article 17, Rome Statute) suggest cooperation’s an option, not a dead end. He’s proud of RA 9851, and fair enough, but it’s a double-edged sword he’s still figuring out.

2. Political Pressure Cooker: Sovereignty, Gaps, and Family Feuds

Sovereignty’s Rally Cry: Remulla’s Fighting the Good Fight

Marcos’s confusion and Remulla’s stand tap into a deep vein of Filipino pride—foreign courts feel like overreach, and Duterte’s 2018 exit sold that story hard. Remulla’s holding the line, and it’s a popular one: why bow to The Hague when Manila’s got its own rules? The catch is the accountability gap—RA 9851’s been around since 2009, but the drug war’s toll (12,000-30,000, say human rights groups) hasn’t seen a big courtroom reckoning. Remulla’s “individuals face proceedings independently” idea sounds noble, but without state muscle, it’s a long shot. He’s defending turf in a world that’s watching—and judging.

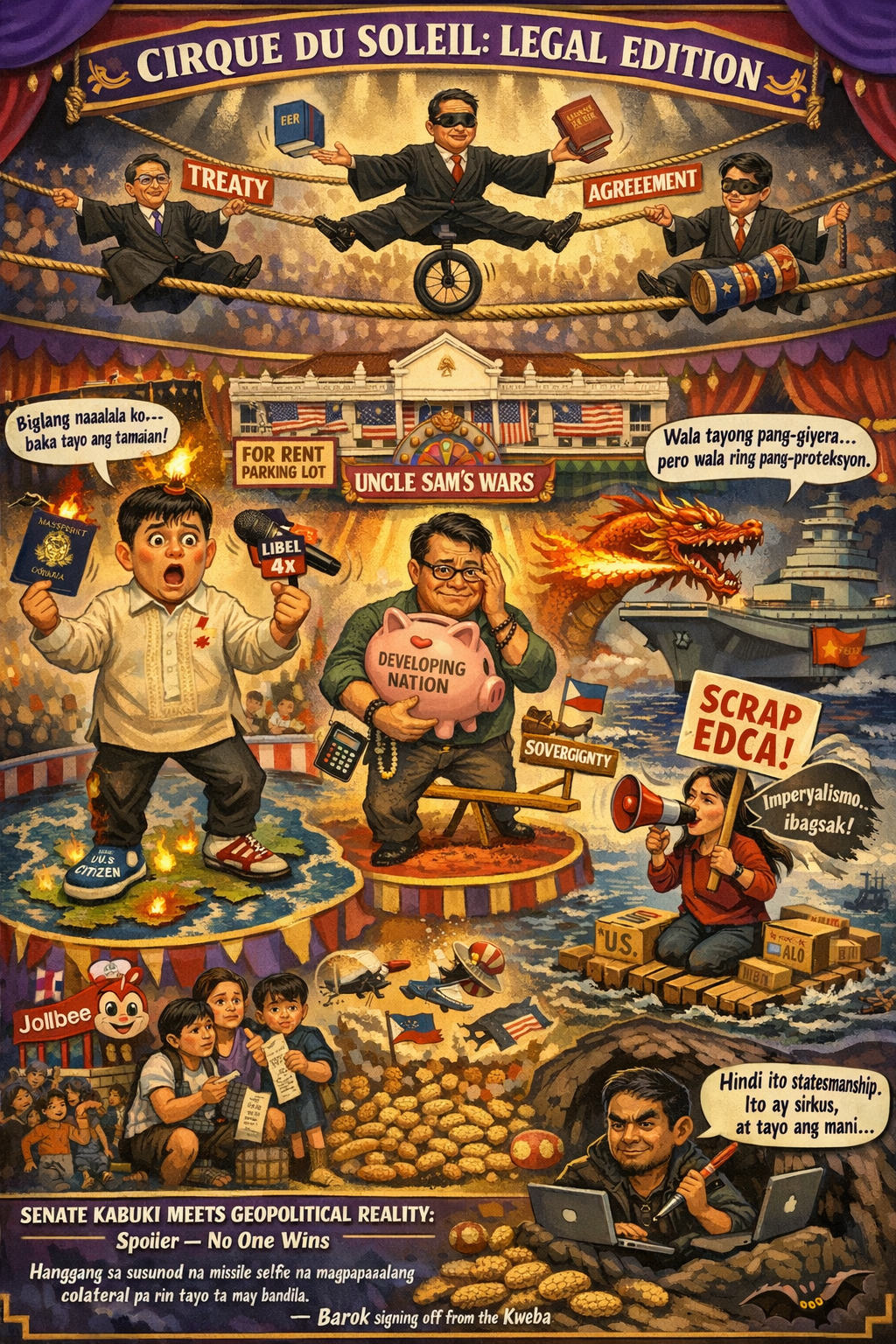

Marcos vs. Duterte: A Soap Opera with Stakes

The Marcos-Duterte split in 2024 turned allies into enemies, and Duterte’s arrest feels like Marcos Jr. settling a score. Remulla’s framing—“not our call, just individuals”—lets the administration play neutral while Interpol does the heavy lifting. It’s a smart dodge ahead of the 2025 midterms, but Duterte’s fans aren’t fooled, and they’re loud. Remulla’s stuck in the middle, trying to keep the peace while dynasties duke it out. It’s less about justice and more about who’s got the upper hand.

Ethical Tightrope: Remulla’s Heart in the Right Place?

RA 6713’s Section 4 demands integrity and justice from officials like Remulla. He’s pushing a tough stance, and you can see the logic—protecting the nation’s dignity isn’t cheap. But with drug war victims still waiting, the UN Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary (1985) nudge him toward impartiality, not just loyalty. Remulla’s not out to duck justice—he’s balancing a hot potato—but the optics of stalling while graves multiply don’t look great.

3. Road Map: Smoothing the Legal and Political Bumps

Legal Harmony: Helping Remulla Find Balance

- Face the Music: Remulla could nod to Article 127(2) and Pangilinan’s hint—own the pre-2019 duties, like sharing old evidence. It’s not surrender; it’s playing by the rules he’s stuck with.

- Flex RA 9851: Kick off real probes under Section 4. If Manila nails Duterte first, the ICC steps back—complementarity’s his friend. No dice? Section 17’s surrender option keeps it legal.

- Own the Interpol Bit: Say the arrest was ICC via Interpol—call it compliance, not conspiracy. Clear rules for Red Notices would give Remulla a firmer footing next time.

Political Peace: Justice Without the Drama

- Shift the Narrative: Marcos Jr. should pivot to a “justice-first” narrative—cooperate with the ICC to prove the Philippines isn’t a human rights pariah. It’s a PR win and a jab at Duterte’s legacy.

- Ethics Boost: Lean into RA 6713—Remulla’s team could pledge drug war answers, ICC or not, to win back trust without looking soft.

- Cut the Family Ties: An independent drug war commission, free of Marcos-Duterte baggage, lets Remulla focus on law, not legacy wars.

The Takeaway: Remulla’s Got a Point, But the World’s Watching

Remulla’s holding a tough line—state sovereignty’s no joke, and he’s not wrong that the ICC targets people, not nations. The Rome Statute, RA 9851, and Pangilinan complicate his story, though—Duterte’s arrest shows the ICC’s still in the game. Imee Marcos’s confusion is either clueless or crocodile tears, but it’s the dynastic feud driving this circus. Remulla’s trying to do right by the Philippines, ethically and legally, but the drug war’s ghosts won’t fade. Manila can dig in or step up—Remulla’s call could shape how this ends.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment