By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — March 25, 2025

IMAGINE Juanito Reyes, a 53-year-old jeepney driver with calloused hands and a sun-creased face, steering his rattling rig through Quezon City’s smog-choked streets. For 30 years, his garish, hand-painted jeepney—adorned with saints and slogans—has ferried students, vendors, and workers for 12 pesos a ride. It’s not just a vehicle; it’s his family’s lifeline, feeding four kids and a wife who mends clothes to make ends meet. Last month, Juanito sold that jeepney—not for profit, but to pay off a loan he took to join the government’s Public Transport Modernization Program (PTMP). Now he’s jobless, his debt lingers, and the “modern” jeepney he was promised remains a distant dream.

Juanito’s story isn’t an anomaly. It’s the human cost of a policy sold as progress but teetering on predation. On March 24, 2025, Department of Transportation (DOTr) Secretary Vince Dizon stood before cameras, promising “openness to changes” in the PTMP and a “solution” within two weeks. His words came as MANIBELA, a transport group, launched a three-day strike, stranding commuters from Las Piñas to Caloocan. Photos of weary passengers—schoolgirls in uniforms, laborers with empty lunch pails—flooded social media, a silent rebuke to a program that’s left the Philippines’ transport backbone fractured.

This is the PTMP’s roadmap: a highway to inequality paved with good intentions and broken promises. Let’s peel back the spin and see what’s really at stake.

Cooking the Books: When 86% Means 40%

The DOTr boasts that 86% of public utility vehicles (PUVs) have applied to consolidate into cooperatives under the PTMP, a figure meant to dazzle. Yet Dizon admits only 40% have been approved. That’s a yawning gap—46% of drivers and operators left in limbo, their applications gathering dust at the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB). “What happened?” Dizon asked aloud, as if he’s just stumbled onto the scene. The answer isn’t a mystery; it’s a scandal.

Transport groups like PISTON cry foul, alleging on X (@pistonph, March 21) that the government’s stats are “cooked”—a charge bolstered by Dizon’s own confusion. Is the 86% a mirage of paperwork, masking a reality where most drivers can’t meet the LTFRB’s opaque requirements? Or is it deliberate exclusion, a bureaucratic chokehold to force out small operators? The DOTr owes us raw data, not rosy percentages. When modernization hinges on transparency, this fog of numbers is a betrayal.

Crushed by Debt, Stranded by Design: Lives in the Balance

At the PTMP’s heart is a gleaming promise: replace rickety jeepneys with Euro 4-compliant units—safer, cleaner, modern. Each costs over 2 million pesos ($35,000), a sum even state banks like LandBank and DBP call “too expensive” for drivers earning, on a good day, 1,000 pesos ($17). The government offers loans with a 5% subsidy, but the math doesn’t bend. Juanito’s cooperative in Iloilo told me drivers now face “starvation wages” (@nednared, March 23), their earnings siphoned by debt payments. Some sell their old rigs to stay afloat; others abandon the trade entirely.

Then there’s the commuters. MANIBELA’s strike left thousands stranded—mothers lugging groceries, students missing exams—because the PTMP’s rollout is a masterclass in disruption without contingency. The DOTr touts long-term gains, but who compensates the woman in Pasay who lost her cleaning job for missing a shift?

And what of the Euro 4 rationale? The Philippines chokes on pollution—Metro Manila’s air quality rivals Delhi’s—but jeepneys account for just 2% of emissions, per a 2023 study from the University of the Philippines. The real culprits? Industrial plants and private cars. Is this green crusade a climate fix or a convenient veneer for pushing small operators off the road, clearing space for corporate fleets? The silence from DOTr on retrofitting existing jeepneys—cheaper, less disruptive—speaks volumes.

Screams from the Streets: The Forgotten Fight Back

“Walang konsultasyon, walang plano!” shouted Marlyne Sahagun, a MANIBELA organizer, as she rallied drivers in Caloocan. “They want us to consolidate, but into what? Debt traps?” Her words cut through Dizon’s platitudes. The PTMP’s consolidation mandate—merging solo franchises into cooperatives or corporations—is pitched as collective empowerment. But drivers see a different story: a loss of autonomy, a handover to entities with deeper pockets. In Baguio, a cooperative head whispered to me, “The big players are circling. We’re just the bait.”

Commuters, too, feel the sting. “I waited two hours,” said Ana Lopez, a vendor in Parañaque, her arms full of unsold fish. “Modernization? Tell that to my kids who went hungry today.” Their voices drown in the DOTr’s echo chamber, where “openness” sounds more like damage control than dialogue. MANIBELA’s strike isn’t just protest—it’s a plea for survival. If Dizon’s two-week fix is performative, not substantive, the jeepney’s soul—vibrant, chaotic, democratic—could vanish.

Rigged Rules, Corporate Creep: The System’s Dirty Secrets

Pull Quote: “When modernization tramples the poor, it’s not progress—it’s predation.”

The PTMP’s financial model is a predatory snare. A 2-million-peso jeepney, even with a 5% subsidy, demands repayments far beyond the average driver’s 300,000-peso annual income. Compare that to Bogotá’s TransMilenio, where phased subsidies and public-private partnerships eased bus operators into modernity without crushing them. Here, the DOTr leans on loans, not lifelines, leaving drivers like Juanito to sink or sell.

Governance is another festering wound. Why does the LTFRB approve just 40% of applications? Dizon’s questions—“Requirements ba nila? Road rationalization?”—hint at incompetence or worse: a system rigged to favor the compliant or connected. X posts (@blcb, March 24) cite Senator Grace Poe demanding “inclusive consultations,” yet the LTFRB’s track record—shrouded guidelines, stalled routes—suggests exclusion is the game.

And consolidation? It’s a power grab dressed as reform. Small operators, the jeepney’s lifeblood, fear absorption by corporations or well-funded cooperatives. In 2019, a DOTr official privately admitted to me that “big transport firms” were eyeing the program’s endgame. Modernization should lift the little guy, not line corporate coffers.

Rewriting the Route: Solutions That Don’t Sell Out

Dizon’s two-week deadline isn’t enough—it’s a Band-Aid on a broken system. Here’s what must change:

- Transparency or Bust: Release the LTFRB’s full consolidation data—applications, approvals, rejections, reasons. No more hiding behind percentages.

- Subsidies, Not Shackles: Slash the 2-million-peso burden with phased grants, not loans. Retrofit older jeepneys with Euro 4 kits—half the cost, twice the equity.

- Hear the Horns: Hold public forums with drivers, not press conferences for podiums. Let Juanito and Marlyne shape the fix.

- Lessons from the Road: Study Bogotá’s balance of state support and operator viability—or heed Kenya’s matatu chaos, where rushed reforms sparked violence.

Progress or Plunder? The Clock’s Ticking

The PTMP could be a triumph: cleaner air, safer rides, a transport system that hums. But when it drives men like Juanito to despair and leaves Ana’s kids hungry, it’s a hollow victory. Modernization should mean progress for all—not a gleaming jeepney parked atop the poor’s wreckage. Dizon has two weeks to prove this isn’t just rhetoric. The Philippines deserves a roadmap that doesn’t dead-end in debt and dust. Let’s demand it.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

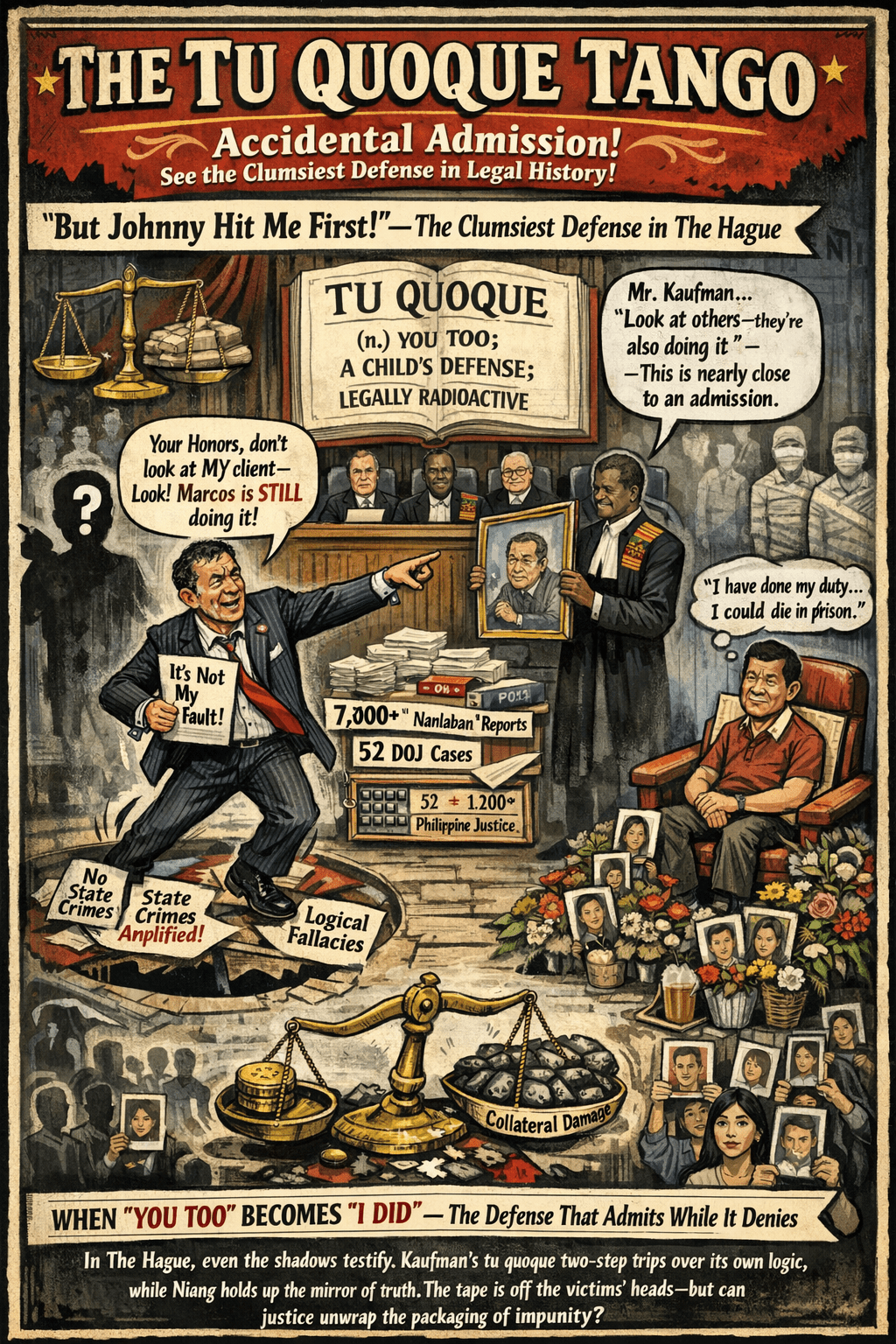

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment