By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — March 27, 2025

The night was thick with humidity off Languyan Island, near Tawi-Tawi, when the boat’s engine coughed its last gasp. Five Chinese nationals, blacklisted and desperate, hunched in the shadows, their escape to Sabah, Malaysia, thwarted not by vigilance but by mechanical failure. The Bangsamoro authorities swooped in, and by dawn on March 23, 2025, the Bureau of Immigration (BI) had them in custody—another notch on Commissioner Joel Anthony Viado’s belt. A press release trumpeted the triumph: coordination with intelligence agencies had foiled a “backdoor exit.” But as the boat sputtered to a halt, a deeper question loomed: Is this a victory for enforcement, or the latest symptom of a system so broken it can’t stop the bleeding?

This isn’t just a story of a failed getaway. It’s an exposé of the Philippines’ immigration quagmire—a porous frontier where shadow economies thrive, global criminals find refuge, and local complicity festers. The arrests of these five, linked to the notorious Lucky South 99 POGO hub, alongside an American drug trafficker and an Egyptian troublemaker, peel back the layers of a crisis decades in the making. Beneath the BI’s headlines lies a dark underbelly: corruption that’s been papered over, transnational crime that’s found a home, and human lives crushed in the machinery of apathy.

Beneath the Neon: Lucky South 99’s Slave Empire

Picture the Lucky South 99 compound in Porac, Pampanga—a sprawling empire of 46 buildings, villas, and a golf course, raided in 2024 after whispers of torture and trafficking grew too loud to ignore. The five Chinese nationals caught in Tawi-Tawi weren’t just overstaying tourists; they were cogs in a Philippine Offshore Gaming Operator (POGO) machine that’s become synonymous with modern slavery. Reports from last year paint a grim picture: workers lured from Indonesia and Vietnam with promises of legitimate jobs, only to be locked in scam farms, their passports confiscated, their bodies bartered. The Securities and Exchange Commission revoked Lucky South 99’s registration in September 2024 for these sins, yet here we are—its operatives still slipping through the cracks, even after President Marcos’ ban.

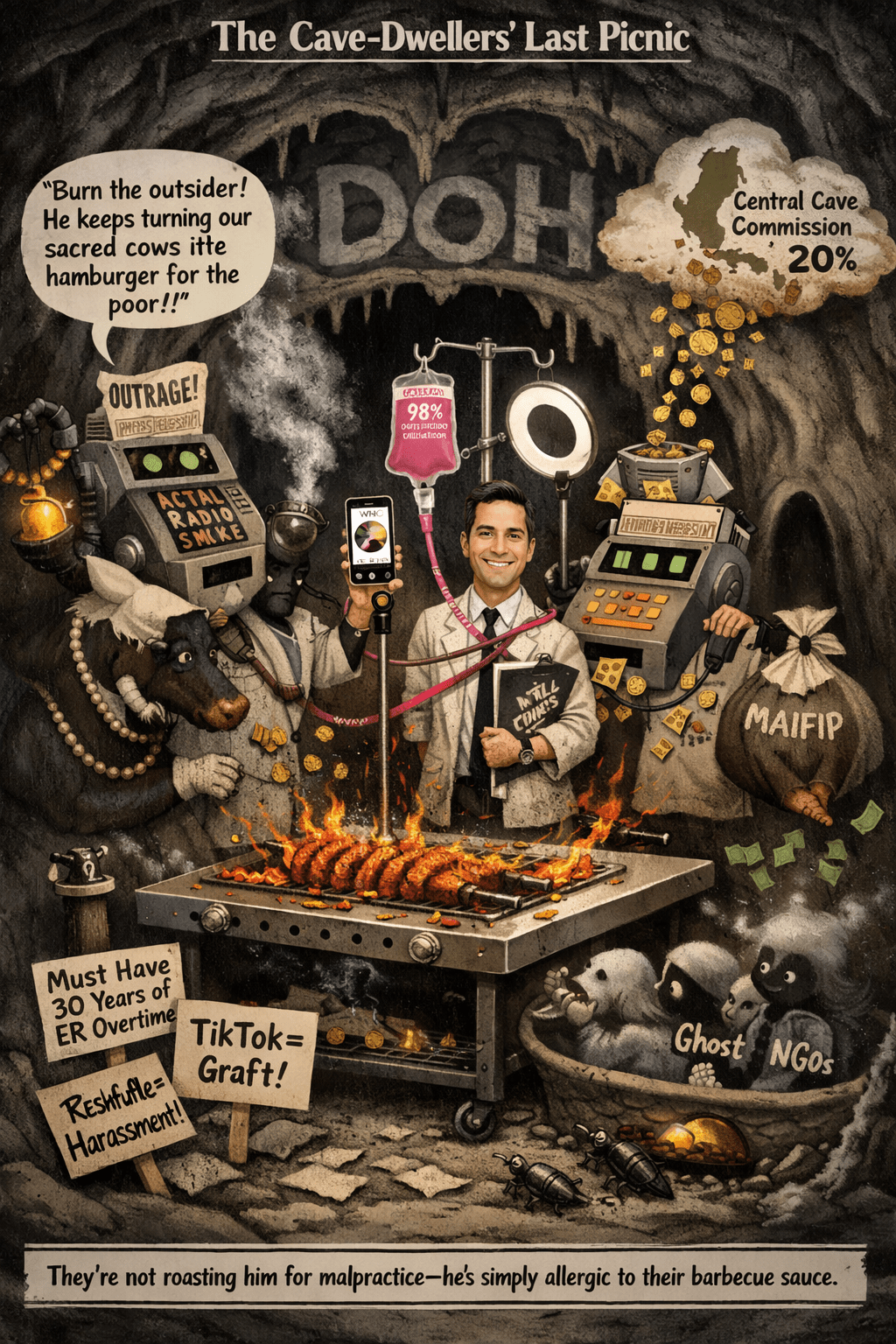

This isn’t new. The BI’s past is stained by the “pastillas scheme,” a 2021 scandal where immigration officers allegedly pocketed bribes—rolled like the Filipino candy—to wave through illegal entrants. Hundreds were implicated; few faced justice. The engine trouble that doomed these fugitives mirrors the BI’s own stalling reforms—a system that catches some, but only after the damage is done. Why were these blacklisted men still in the country, free to plot their escape months after the POGO shutdown deadline? The answer lies in a bureaucracy that’s long been more sieve than shield.

Cartels in the Countryside: A Global Criminal Haven

Then there’s Henry Watkins, alias “Tutu,” a 51-year-old American nabbed on March 18 in Polangui, Albay. Wanted by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration for ties to the Sinaloa cartel—infamous for flooding streets with fentanyl—he’d overstayed his welcome in the Philippines, hiding in plain sight. How does a man with such a rap sheet find sanctuary here? The BI’s coordination with the U.S. government to nab him is commendable, but it begs a chilling question: How many more like Watkins are nestled in barangays across the archipelago, shielded by lax oversight?

The Philippines isn’t just a waypoint for POGO fugitives—it’s a node in a global web of crime. Watkins’ arrest exposes an immigration system that inadvertently rolls out the red carpet for transnational predators. The Sinaloa connection isn’t a fluke; it’s a symptom of borders too weak to filter out the world’s worst. And what of the Egyptian, Bakhit Akram Mnayer Gouda, arrested in Naga City for assault and “immoral acts”? His petty crimes pale beside Watkins’, but together they illustrate a spectrum of failure—from sheltering kingpins to tolerating small-time menaces.

Ghosts of Exploitation: The Human Cost Uncounted

Behind the statistics are the voiceless. I think of Mei, a pseudonym for a woman I imagine trapped in Lucky South 99’s grip—recruited from a rural Chinese village with promises of a call-center job, only to find herself scripting love scams under threat of violence. Her story echoes the 186 workers rescued from the Porac raid last June—foreigners and Filipinos alike, some allegedly tortured, others sold for sex. In Tawi-Tawi, fishermen whisper of “transporters,” shadowy locals who ferry fugitives for a fee. Who are they? How deep does their network run? The BI pats itself on the back for this bust, but what of the communities these operators exploit—the barangays turned transit hubs, the families left to fend off the fallout?

Henry Watkins’ neighbors in Polangui tell a quieter tale. “He kept to himself,” one might say, “but we knew something wasn’t right.” A drug trafficker in their midst, and no one sounded the alarm until the BI knocked. This isn’t just enforcement lag; it’s systemic apathy—leaving rural Filipinos to bear the burden of a government that’s slow to act until headlines force its hand.

Viado’s Tightrope: Reform or a Rosy Facade?

Enter Commissioner Joel Anthony Viado, a man who touts “strong collaboration” as his battle cry. The BI’s arrest of 180 foreign fugitives in 2024—up from who-knows-how-few under past regimes—is a feather in his cap. His press release gushes about intelligence coordination, and the Tawi-Tawi bust proves it’s not all hot air. The forensic document lab opened at Clark last November hints at a tech-savvy push to plug the leaks. Yet skepticism gnaws. The pastillas ghost lingers—corruption isn’t uprooted by directives alone. How many of those 180 were deported? How many cases crumbled under courtroom scrutiny? Viado’s reforms look promising, but transparency is the litmus test. Without hard numbers—deportation stats, conviction rates—his “turning point” feels more like a press kit than a pledge.

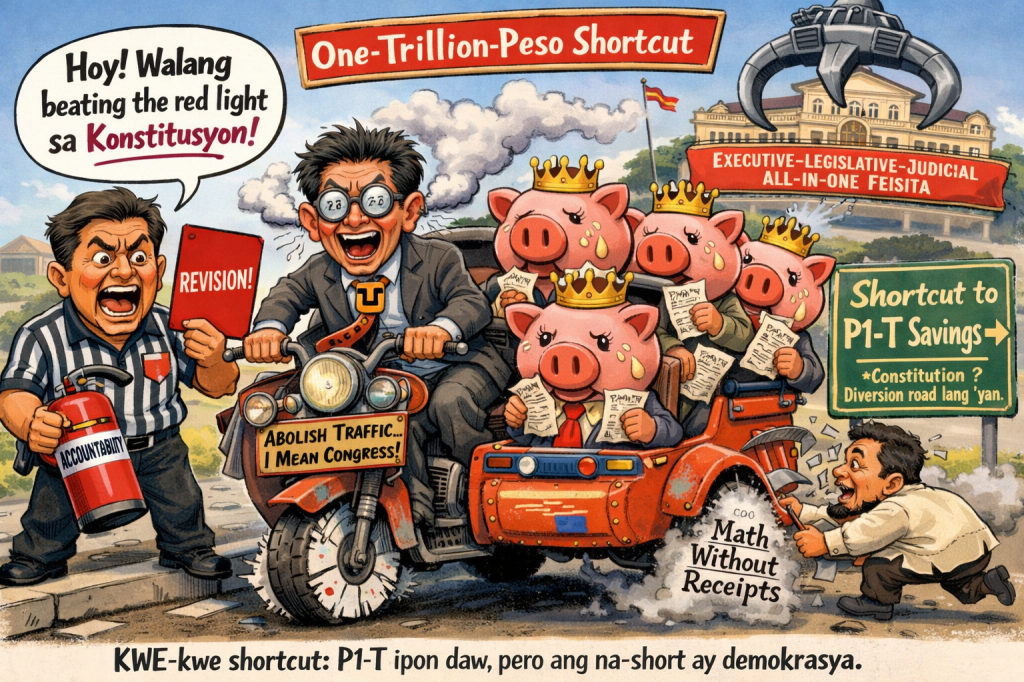

Blueprint for Redemption: Sealing the Cracks in Marcos’ Ban

President Marcos dealt a blow to POGOs with his July 2024 ban, cemented by Executive Order No. 74 and a December 31 deadline—80% of hubs shuttered, 27,000 workers deported. Yet the boat off Tawi-Tawi tells a different tale: the ban’s a sieve, not a seal. Some 100 “guerrilla” POGOs persist, with 11,000 foreign workers dodging the dragnet, fueling crime from the shadows. Here’s how to finish the job:

First, turbocharge enforcement. Flood the BI and the Presidential Anti-Organized Crime Commission with funds for boots on the ground—raids on these stealth hubs can’t wait for tips. Second, choke the “transporters.” Offer cash rewards and legal immunity to locals who expose smuggling rings; turn Tawi-Tawi’s fishermen into sentinels, not accomplices. Third, track the ghosts. Deploy real-time visa monitoring and facial recognition at ports—Watkins shouldn’t have lasted a month, let alone years. Fourth, rescue the Meis. Fund a task force for POGO victims—safe houses, legal aid, repatriation—before they vanish into underground dens.

Finally, demand accountability. Mandate quarterly BI reports: arrests, deportations, convictions—no more vague “180” boasts. Audit barangay officials in hotspot zones; complicity thrives where oversight dies. Marcos’ ban was a thunderclap; these steps make it a reckoning. Half-measures won’t kill a hydra that’s already gone guerrilla.

Last Stand at the Border: A Nation’s Reckoning

The boat’s breakdown off Languyan wasn’t fate—it was a flare illuminating a rotting core. The Philippines can’t keep playing whack-a-mole with POGOs and fugitives. It needs a reckoning: dismantle the shadow economies, protect the whistleblowers, track the Watkinses before they settle in. This is more than policy—it’s a moral cry. Will the Philippines rise as a rule-of-law beacon, or sink deeper into the mire as a haven for exploiters? Mei’s fate, and millions like her, hangs in the balance. The BI’s net caught seven this month, but the sea is vast, and the leaks are many. The engine’s fixed now, but the system’s still sputtering. Time’s running out to steer it right.

Leave a comment