By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — April 8, 2925

It began, as so many luminous lives do, not with applause, but with shadows waiting to be transformed. One imagines the year was 1968, in the dusk-hallowed halls of the University of the Philippines’ Abelardo Hall, where a young undergraduate—sharp of wit, wide of eye—stood at the edge of a modest stage and conjured into being Tisoy, a comic-strip world come to life. There, Tony Gloria, then unknown to the future that would bend in deference to his name, directed and co-wrote a play so resonant it demanded a second staging weeks later. This was not hubris. This was prescience. It was Tony’s first public act of synthesis: merging the populist pulse of Marcelo’s satire with the rigors of stagecraft, comedy with critique, the everyday with the enduring.

From that radiant origin unfurled a life lived in layers of light—projector light, limelight, the metaphorical incandescence of a man who saw in the mundane a flicker of story, and in story, revolution.

To speak of Antonio “Tony” Gloria solely in the vocabulary of cinema and advertising is to forget that true visionaries are never bound by their mediums. They are bound only by the desire to bring others with them. “Mr. G,” as he was known with equal parts reverence and affection, did not so much build an empire—Unitel Pictures, Straight Shooters Media, the scaffolding of Cinemalaya—as he did a fellowship. In a cultural landscape often clouded by compromise, he remained the rarest of phenomena: a man of principle who still knew how to sell a laugh, a sigh, a story.

His legacy in advertising was meteoric. Named one of the 25 Mavericks by the 4As and a Creative Guild Lifetime Achievement Awardee, Tony rewrote the grammar of persuasion. Yet, he did so not by shouting louder but by listening better. Listening to what the Filipino wanted. More importantly, what the Filipino feared, loved, dreamed. His commercial work shimmered with craft, yes, but also with conscience. And perhaps that is what separates an adman from an artist: Tony Gloria was both, in the same way that light is both particle and wave.

Mark Meily once recalled the day Tony said “yes” to Crying Ladies. Just one word. One syllable. Yet in it was a lifetime of risk-taking, of belief in the unseen. “That one act of trust,” Meily said, “changed my life forever.” In this, Tony became not merely a producer but a midwife to visions not his own. He understood, as the best mentors do, that to nurture others is not to diminish oneself but to multiply endlessly.

Madonna Tarrayo, who journeyed from colleague to CEO under his tutelage, spoke of his dual nature with tenderness: “To those who don’t know him, Mr. G can be intimidating… but he was really soft-hearted.” It is this soft-heartedness—half-guarded, wholly generous—that pulses at the center of Tony’s mentorship. A silhouette of stoicism, yet a heartbeat of generosity.

That he was Upsilonian, a proud member of Upsilon Sigma Phi, is no minor footnote. It is an emblem. For the fraternity’s creed—we gather light to scatter—could well have been inscribed across every frame Unitel ever committed to celluloid. His brotherhood did not end in ceremony. It was lived: in the way he uplifted young directors, trusted bold screenplays, refused mediocrity, demanded brilliance, and offered second chances when brilliance stumbled.

And oh, how the films gleamed: American Adobo’s diasporic ache, La Visa Loca’s absurdist migration, Inang Yaya’s maternal quiet, Santa Santita’s sacrilegious grace. These were not films of formula. They were invitations—to laugh, to grieve, to understand. They were mirrors and windows, reflecting us while showing us who we might become.

But let us not speak only of work. Let us speak of presence. That empty chair in Unitel’s office, once occupied by a man who made rounds not out of obligation but out of curiosity, is now a shrine of sorts. A reminder that mentorship is not an event but a rhythm. A series of conversations. Sometimes about film. Sometimes about family. Sometimes about chismis. Always, about connection.

In the end, Tony Gloria did what all great artists aspire to do: he translated life into language—whether cinematic, commercial, or simply human. He proved, over and over, that to be Filipino was not a limitation but a palette. That creativity was not a solitary act but a communal offering. That it was, in his favorite phrase, always possible. Puwede pala yun.

And so, we return to where we began. To that boy in Abelardo Hall, pulling curtains on a comic strip made flesh, already scattering light. From Diliman’s halls to the silver screen, he scattered light like a man who knew the dark, but refused to let others walk in it alone.

Farewell, Mr. G. The reel does not end—it simply flickers into memory. And what a memory you’ve left us with.

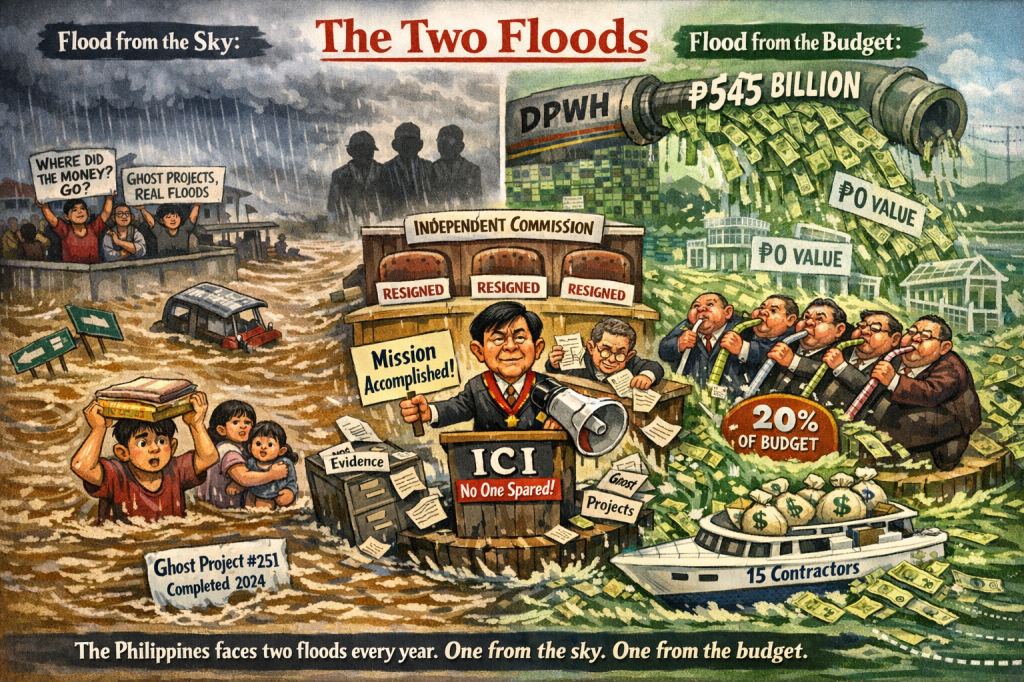

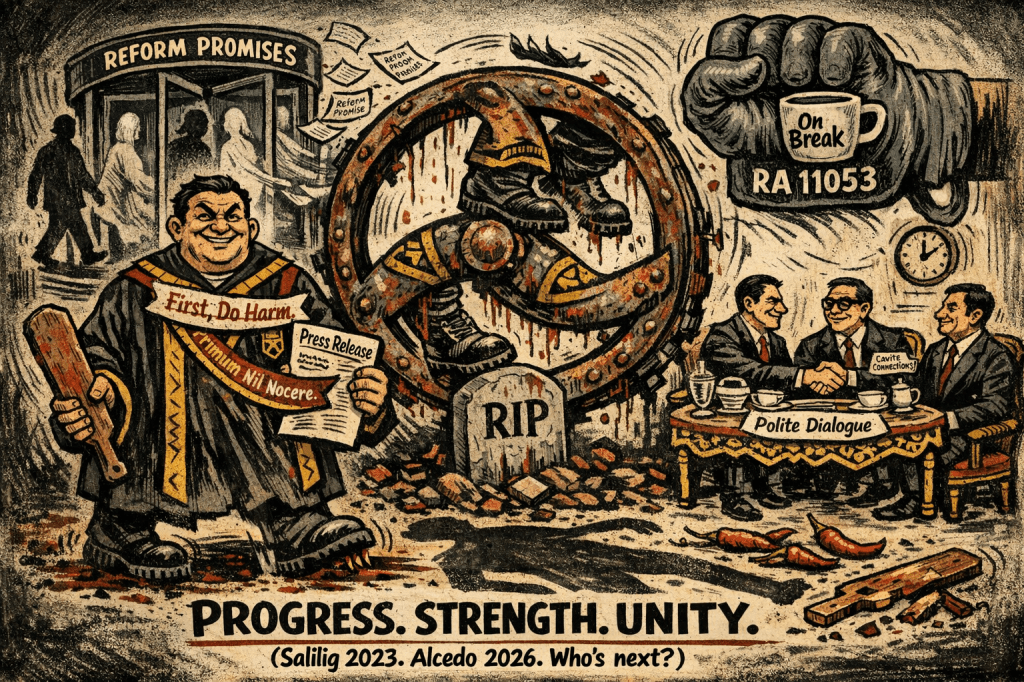

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

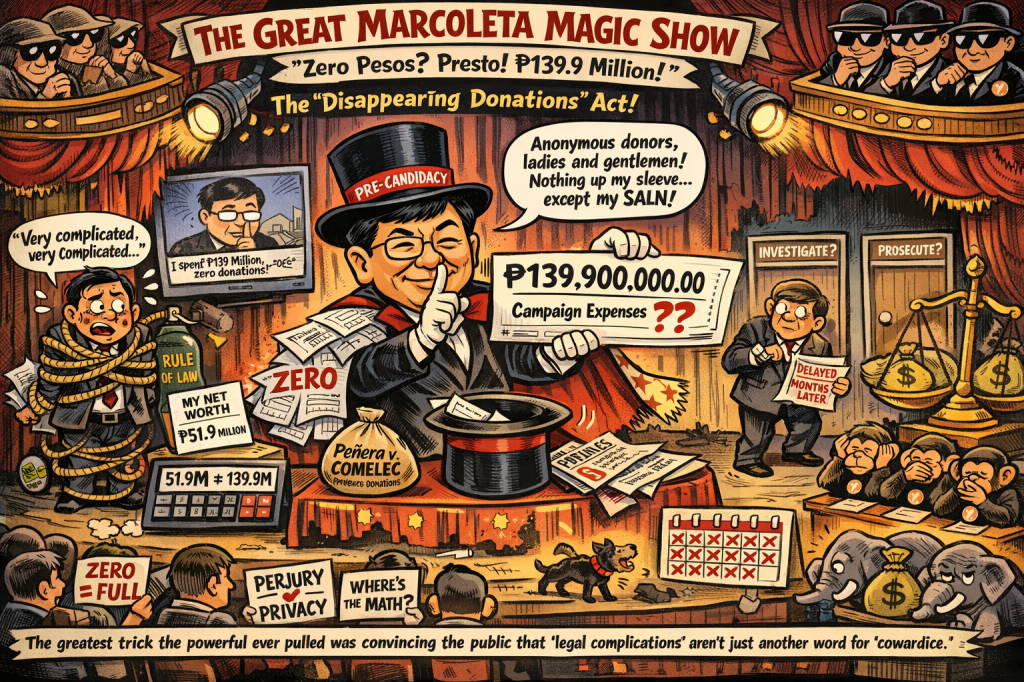

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

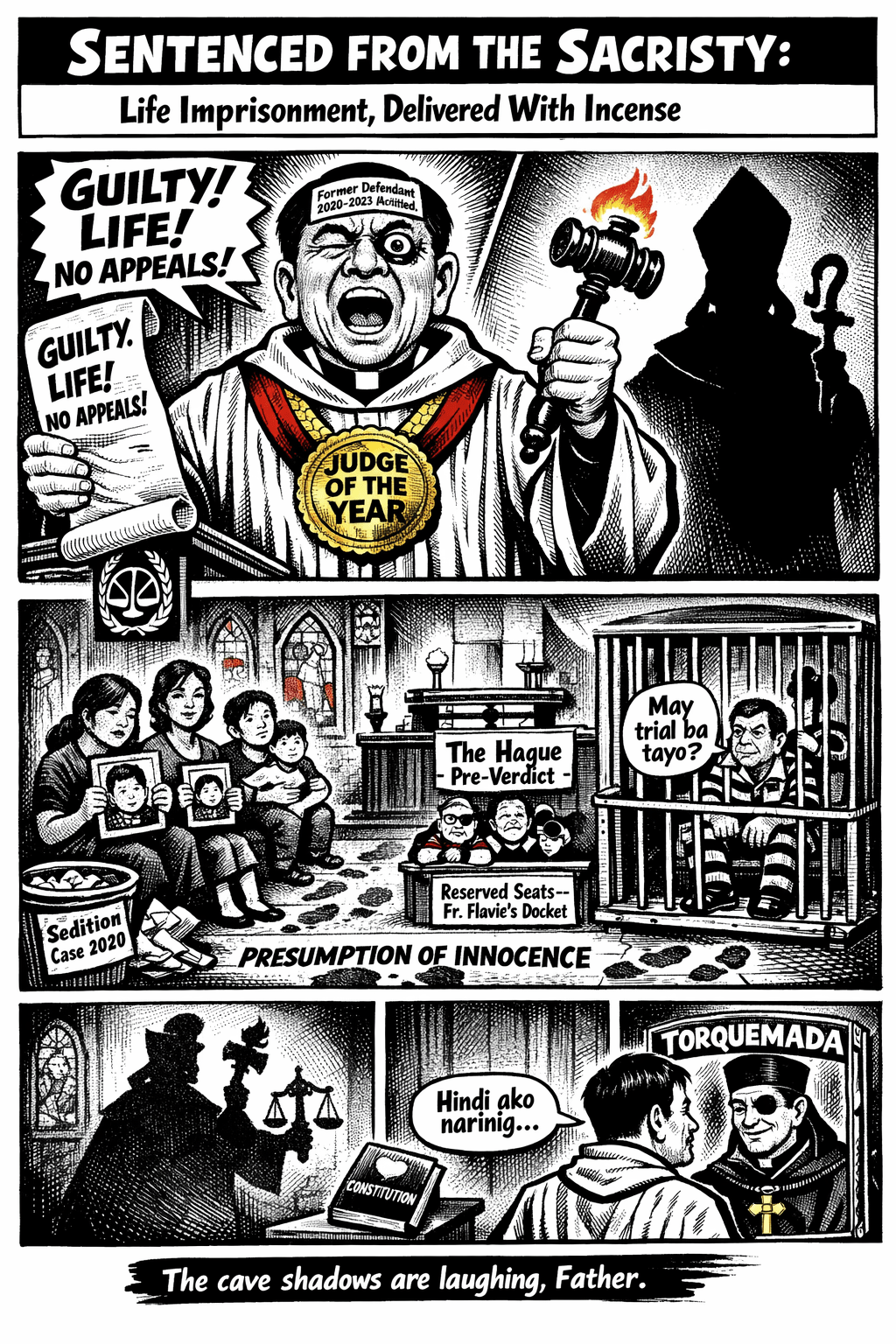

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment