By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — April 11, 2025

AT THE Hague, a legal chess game is underway. On one side: the International Criminal Court (ICC). On the other: Rodrigo Duterte’s defense team, armed not with facts, but with bureaucracy. Their latest move? Demanding national IDs from drug war victims’ families—hoping the red tape buries the dead twice. The ICC must respond with clarity and courage.

The Victim-Silencing Conspiracy

Rodrigo Duterte, former Philippine president, sits in ICC custody facing charges of crimes against humanity for his drug war, which left an estimated 6,000 to 30,000 dead—mostly poor men gunned down in slums. The stakes couldn’t be higher for victims’ families, who seek to participate in the proceedings not just for reparations but to reclaim dignity stolen by state-sanctioned violence. Yet, Duterte’s defense, led by Nicholas Kaufman, is waging a procedural war to exclude them, demanding stringent identification requirements and unified legal representation through the ICC’s Office of Public Counsel for Victims (OPCV). The asymmetry is stark: a well-funded legal team, backed by Duterte’s political machine, faces off against marginalized families, many of whom lack the means to navigate bureaucratic hurdles.

The irony drips like venom. Kaufman invokes Duterte’s “right to a speedy trial” to justify streamlining victim participation, yet his tactics—piling on documentation barriers and delaying victim inclusion—seem designed to bog down the process. How fortunate that Duterte’s team suddenly cares about bureaucratic efficiency when it serves to mute the voiceless.

“Limiting the range of identity documents enhances the reliability of the identity verification process and significantly reduces the risk of fraud.”

—Nicholas Kaufman, Duterte’s lead counsel, in an April 7, 2025, ICC filing.

Stacking the Deck Against Justice

Let’s dissect Kaufman’s arguments with a scalpel. First, the demand for national IDs or passports as proof of victim status is procedural obstruction masquerading as fraud prevention. The Philippines’ national ID system is a notorious mess—plagued by backlogs, underfunding, and inaccessible registration centers, particularly for the rural and urban poor. A 2023 report noted that only 60% of Filipinos had received their national IDs despite years of rollout, with marginalized communities disproportionately excluded. Passports? Even more absurd. They’re a luxury for the elite, not the slum-dwelling families whose loved ones were executed in Duterte’s “war.” Kaufman’s fallback—IDs accepted by the Social Security System (SSS)—ignores that SSS coverage skews toward formal workers, not the informal sector where most victims resided.

Contrast this with ICC precedent. In Prosecutor v. Lubanga (2011), the court allowed flexible identification methods, including community leader affidavits and school records, recognizing that war-torn communities often lack formal documents. The Lubanga chamber explicitly warned against “overly restrictive” criteria that could “undermine the rights of victims to participate.” Kaufman’s proposal flouts this, betting that bureaucratic exclusion will shrink the victim pool to a manageable, less damning number.

“Their insistence on the use of national IDs is unrealistic… Their suggestion to produce passports is anti-poor, as only the socially mobile have the luxury to avail of cross-country travel.”

—Kristina Conti, ICC assistant to counsel, exposing the defense’s bias.

Then there’s the representation gambit: Kaufman’s push for OPCV-only representation, dismissing victims’ chosen counsel as “unwieldy.” This isn’t just logistical nitpicking—it’s a potential violation of Article 68(3) of the Rome Statute, which guarantees victims the right to present their views “in a manner… not prejudicial to or inconsistent with the rights of the accused.” The ICC has long upheld victims’ freedom to select counsel, as seen in Prosecutor v. Katanga (2014), where diverse legal teams were accommodated to ensure authentic representation. Forcing victims into the OPCV’s one-size-fits-all model risks diluting their agency, turning their pain into a bureaucratic checkbox. It’s a cynical move to limit the scope of victim narratives, ensuring fewer voices pierce Duterte’s defense.

The Dirty Politics Behind the Curtain

Kaufman’s tactics don’t exist in a vacuum—they echo Duterte’s playbook of delegitimizing victims. His drug war thrived on dehumanizing rhetoric: “drug pushers” weren’t people but vermin to be eradicated. Now, Kaufman’s “false victims” narrative recycles that venom, casting doubt on grieving families’ legitimacy. This isn’t new. Duterte’s allies have long weaponized disinformation, and the current online harassment campaign against victims—labeling them “fake” or “paid”—bears the hallmarks of state-sponsored troll farms that fueled his 2016 rise. Conti has flagged this abuse, noting that at least ten victims seeking ICC participation face digital vitriol. It’s not just harassment; it’s a calculated effort to intimidate survivors into silence.

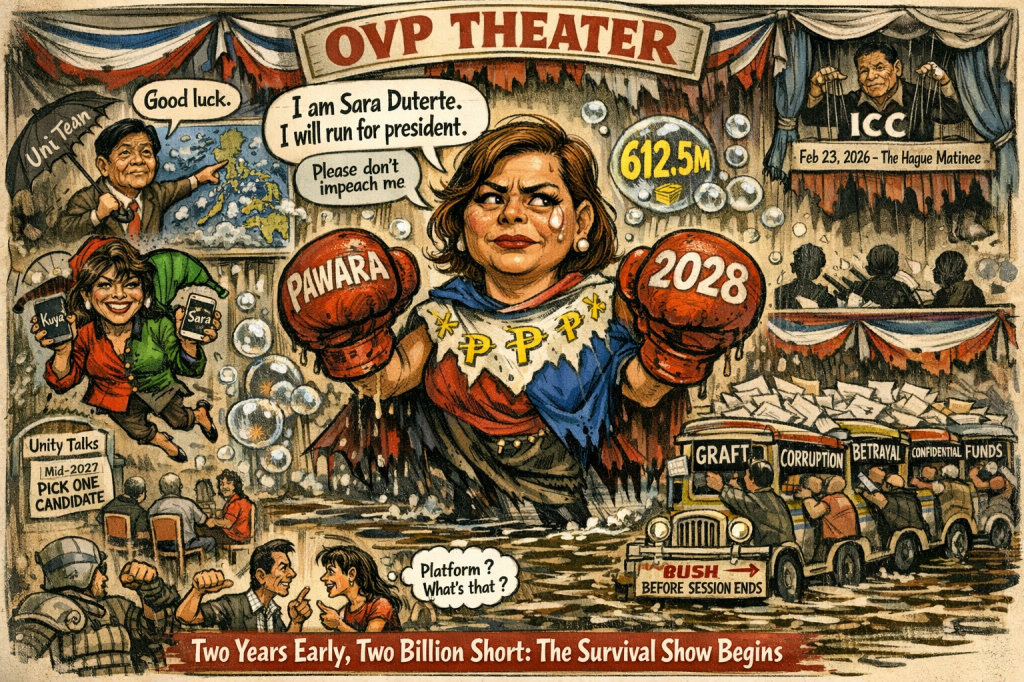

This political shadow looms large. Duterte’s daughter, Vice President Sara Duterte, continues to rally loyalists, framing the ICC case as a sovereignty violation. Kaufman’s legal maneuvers dovetail with this narrative, painting victims as pawns in a globalist plot. The defense’s obsession with “fraud” isn’t about evidence—it’s about sowing distrust, a tactic straight from the authoritarian handbook.

Will the ICC Fold or Fight?

The ICC’s mandate is clear: victims are central to its mission, not peripheral props. Yet, resource disparities tilt the playing field. Kaufman’s team, flush with Duterte’s political capital, can afford to file voluminous motions and exploit procedural loopholes. Victims’ lawyers, like Conti, rely on underfunded NGOs like Rise Up for Life and Rights and pro bono work, stretched thin across thousands of potential applicants. This imbalance isn’t just unfair—it’s a structural flaw. The ICC’s victim participation framework assumes a level of access that doesn’t exist for the Philippines’ poor, where legal aid is scarce and trauma lingers.

Worse, the ICC’s own procedures can inadvertently enable exclusion. Rigid documentation standards, while well-intentioned, clash with the reality of systemic poverty. In Prosecutor v. Bemba (2016), the court grappled with similar issues, ultimately broadening ID criteria to include witness statements. Yet, Pre-Trial Chamber I’s hesitation to preemptively reject Kaufman’s demands risks legitimizing his anti-poor bias. If the ICC bends to these tactics, it hands Duterte a victory before the trial begins, undermining its credibility as a court for the powerless.

How to Smash the Defense’s Game Plan

The ICC must act decisively. First, it should reject Kaufman’s ID demands and adopt alternative verification methods—affidavits, community leader endorsements, or barangay records—aligned with Lubanga precedent. Second, it must uphold victims’ right to chosen counsel, dismissing OPCV monopolization as a transparent ploy to muzzle diverse voices. The Registry’s April 2, 2025 deadline for victim participation observations is a chance to set a firm line.

Philippine civil society has a role, too. Groups like Rise Up for Life and Rights should intensify efforts to document victims, partnering with local governments to bypass national ID bottlenecks. A public campaign to register indirect victims could turn Kaufman’s bureaucracy against him, flooding the ICC with verified applicants.

Finally, the media must amplify Conti’s “anti-poor” framing. Every outlet covering the ICC should ask: why does Kaufman’s fraud obsession target the most vulnerable? Exposing this bias isn’t just reporting—it’s holding power to account.

The ICC was created for cases like this—but only if it doesn’t look away.

Disclaimer: This is legal jazz, not gospel. It’s all about interpretation, not absolutes. So, listen closely, but don’t take it as the final word..

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment