By Louis ‘Barok‘ C Biraogo — April 14, 2025

Prelude: The Sky’s Silent Applause

On April 12, 2025, the heavens dimmed their lanterns. Pilita Corrales, Asia’s Queen of Songs, slipped into the cosmos at 85, her voice—a silk bridge between Manila and the Milky Way—now a whisper in the stars. Her passing was no curtain fall but a celestial encore, the universe leaning in to hum her lullabies. For seven decades, she embroidered the archipelago’s heartbeat onto vinyl, stage, and screen, her repertoire a tapestry of English, Spanish, Tagalog, and Cebuano. To mourn her is to celebrate a symphony of identities—singer, actress, host, mentor, mythmaker—who mapped fault lines between tradition and transcendence.

Movement I: The Australian Meteor Rise

Before Kylie Minogue’s sequins caught the light, there was Pilita—gold records written in stardust. In the late 1950s, a Cebuana barely out of her teens landed in Melbourne, armed with a guitar and a voice like molten amber. Her original, Come Closer to Me, clawed its way to the top of Australia’s pop charts—the first Filipina, the first woman, to claim that crown. She was no mere visitor; she was a pioneer, christened among the “Great Dames of Victorian Radio and Television.” A Melbourne street bears her name, as if the city itself refused to forget the girl who sang I’ll Take Romance with Arthur Young, her notes stitching Visayan folk to global jazz. Yet, offstage, she was grace incarnate—mentoring a young Regine Velasquez, laughing with Annabelle Rama, her ex-lover’s wife, proving harmony could exist beyond the spotlight.

Movement II: The Caesars Palace Coronation

Las Vegas, 1970s. Caesars Palace, a coliseum of glitter and gamble, welcomed its first Filipina. Sammy Davis Jr., dazzled by her fire, handed her the scepter; Pilita sang back in Cebuano. Noche de Ronda curled through the air, Spanish and defiant; Usahay followed, a Visayan lullaby cradling the crowd. Arranged by National Artist Ryan Cayabyab, her set wove four languages into a single spell. She didn’t perform—she conjured. Her backbend, iconic and impossible, wasn’t a trick; it was the archipelago arcing toward the divine, her voice bending spines and notes alike. From Manila’s Grand Opera House to Tokyo’s 1972 Music Festival, where she bested Olivia Newton-John, Pilita was a comet in a terno, leaving constellations in her wake.

Movement III: The Upsilon Genesis

Rewind to 1956. A 17-year-old Pilita, Cebuana Athena, steps onto the University of the Philippines’ stage. Upsilon Sigma Phi, that brotherhood of scribes and dreamers, casts her in Linda, their Cavalcade production. No dynastic privilege, only the alchemy of talent meeting opportunity. The fraternity’s ivy-clad halls, steeped in equations and sonnets, became her first coliseum. Her guitar wasn’t an instrument—it was a divining rod, summoning storms. Kapantay ay Langit’s nascent notes trembled in her throat, a prophecy of the anthems to come. Talentium.ph recalls her as “a girl with a guitar, igniting UP’s stage like a match struck in a cathedral.” This was no mere debut; it was mythmaking, the cosmos taking note of a voice that would soon suture continents.

Coda: Legacy as Landscape

Pilita Corrales was not one woman—she was a chorus. Her 135 albums, from A Million Thanks to You (translated into seven tongues) to Matud Nila echoing in Melbourne’s alleys, charted the Philippines’ soul. As host of An Evening With Pilita, she redefined television; as the Jukebox Queen, she danced through 1960s cinema; as a judge on The X Factor Philippines, she crowned new stars. Her kindness was her quietest aria—befriending Rama, nurturing Velasquez, loving her children Jackielou, Ramon Christopher, and VJ fiercely. Her granddaughter Janine Gutierrez called her “mami and mamita,” a woman whose generosity outshone her FAMAS Lifetime Achievement Award.

She mapped the fault lines between tradition and transcendence—every note a tectonic shift. Her Spanish Vaya Con Dios and Cebuano Rosas Pandan were not songs but bridges, linking Lahug’s shores to Las Vegas’ stages. She was the architect of a culture that refused to be singular, her voice a kundiman’s ache and a Nobel laureate’s clarity.

And so it began: Upsilon Sigma Phi’s stage, a girl’s guitar, and the universe leaning in to listen. Pilita’s farewell? A million thanks, indeed—each one a star sewn into the sky’s silent canopy.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

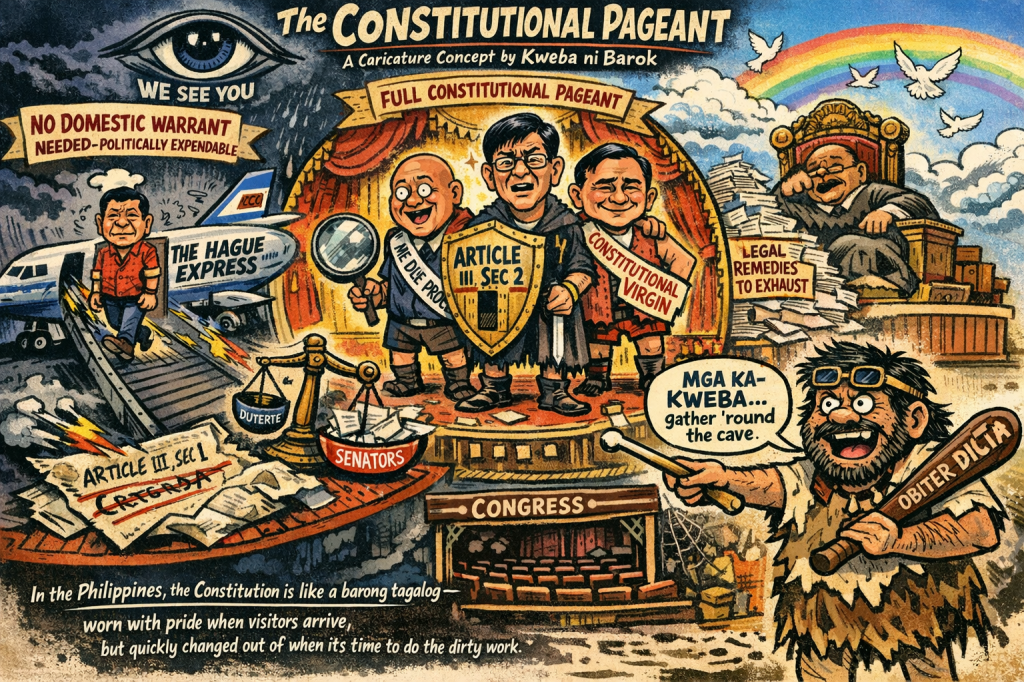

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment