By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — April 15, 2025

Republic Act No. 12144 (link to Official Gazette pending publication), which reassigns vast swaths of NORDECO‘s franchise areas to Davao Light, has sparked a legal firestorm that could reshape the Philippines’ power distribution landscape. This isn’t just a corporate turf war—it’s a constitutional cage match pitting a rural electric cooperative against a private juggernaut, with rural consumers caught in the crossfire. NORDECO claims RA 12144 is an unconstitutional overreach, a legislative sleight-of-hand that tramples due process and cooperative autonomy. Davao Light, backed by consumer advocates waving efficiency flags, insists it’s a public interest win. Kweba ng Katarungan dives into the legal quagmire, dissecting constitutional claims, statutory contradictions, procedural missteps, and the litigation landmines ahead. Buckle up—this is no ordinary blackout.

I. The Constitutional Battle: Is RA 12144 a Legislative Heist?

Non-Delegation Doctrine and Due Process (Art. III, Sec. 9, 1987 Constitution)

NORDECO argues RA 12144 effectively revokes its existing franchises without due process, violating the non-delegation doctrine and the due process clause. Under Presidential Decree No. 269 (PD 269), electric cooperatives like NORDECO were granted franchises with defined service areas, arguably vesting them with property-like rights. The Supreme Court in NEA v. COA (G.R. No. 226540, 2017) recognized cooperatives’ operational autonomy, suggesting franchises aren’t mere privileges but protected interests. Yanking these without a judicial or regulatory hearing smells like a legislative overreach.

But here’s the rub: The Supreme Court’s ruling in ILECO I, et al. v. Executive Secretary Bersamin, et al., (G.R. No. 264260, July 30, 2024) held that electric cooperatives lack exclusive constitutional rights to their franchise areas. Congress, per Article XII, Sec. 11, holds plenary power to grant or modify utility franchises. Does this greenlight RA 12144’s reassignment? Not so fast—G.R. No. 264260 dealt with new franchises, not the revocation of existing ones mid-term. NORDECO’s franchises (valid until 2028 for mainland areas, 2033 for Samal) weren’t expired, raising a red flag about retroactive deprivation.

Equal Protection (Art. III, Sec. 1)

NORDECO cries foul, claiming RA 12144 favors Davao Light, a private corporation, over a cooperative serving rural poor, violating equal protection. The 1987 Constitution prioritizes cooperatives for their social equity role (Art. XII, Sec. 15). Handing NORDECO’s turf to an Aboitiz-led giant could be seen as discriminatory, especially absent evidence that NORDECO failed its mandate.

Counterpoint: Davao Light’s backers, like the Davao Consumer Movement, argue the law promotes equality by ensuring better service for consumers tired of NORDECO’s outages (242.33 minutes annually vs. Davao Light’s 209). Yet, the strict scrutiny test applies to laws affecting fundamental rights like property. RA 12144’s preference for Davao Light lacks a compelling state interest if NORDECO wasn’t proven derelict—a weak link in the law’s armor.

Presidential Inaction: A Tacit Veto?

RA 12144 lapsed into law on April 6, 2025, without President Marcos‘s signature, per Art. VI, Sec. 27(1). NORDECO interprets this as disapproval, citing Philippine Judges Ass’n v. Prado (G.R. No. 105371, 1993), where presidential inaction signaled policy doubts. Marcos previously vetoed a similar bill (HB 10554) in 2022, calling it “constitutionally flawed” under EPIRA.

But: Inaction isn’t a veto—it’s a constitutional quirk that lets bills become law. The Supreme Court has rarely overturned laws based on presidential passivity alone. NORDECO’s argument here feels more like a Hail Mary than a knockout punch.

II. Statutory Smackdown: Does RA 12144 Flout the Law?

PD 269 (1973): Exclusivity or Not?

PD 269, which created the cooperative framework, grants NORDECO franchises with defined areas, implying geographic exclusivity to ensure rural electrification. NORDECO argues RA 12144’s reassignment nullifies this statutory promise mid-term, a view bolstered by NEA v. COA‘s emphasis on cooperative independence.

Counterpoint: G.R. No. 264260 clarified that cooperatives don’t have a statutory lock on their areas—Congress can redraw lines for public interest. Yet, PD 269’s intent was to protect cooperatives from private encroachment, not to expose them to legislative whims. RA 12144’s silence on compensating NORDECO for lost areas undermines PD 269’s spirit.

EPIRA (RA 9136): Anti-Monopoly or Pro-Consumer?

EPIRA’s Sec. 23 bans monopolistic practices in power distribution, aiming for competition and consumer choice. NORDECO claims RA 12144 creates a de facto monopoly by handing Davao Light control over Davao del Norte and Davao de Oro, sidelining a cooperative serving 80,000+ households.

Flip side: Sec. 2 of EPIRA prioritizes “reliable and affordable” power. Davao Light’s lower brownout stats (209 vs. 242.33 minutes) fuel arguments that it better serves EPIRA’s goals, as seen in Mactan Electric Co. v. ERC (G.R. No. 250214, 2021), where franchise tweaks were upheld for efficiency. Problem is, EPIRA also mandates rural electrification (Sec. 59), which NORDECO claims it’s better positioned to deliver in underserved sitios. RA 12144’s consumer focus might trump anti-monopoly rhetoric, but it risks starving rural programs.

NEA Reform Act (RA 10531): Member-Consumer Rights Ignored?

Sec. 4(b) of RA 10531 mandates the National Electrification Administration (NEA) to protect cooperative members’ rights, including stable service. NORDECO argues RA 12144 disenfranchises its member-consumer-owners by transferring their areas without consent, potentially hiking rates under Davao Light’s profit-driven model.

But: NEA’s silence is deafening—no record shows it opposed RA 12144 during deliberations. Was NEA sidelined, or does it implicitly back Davao Light’s track record? The Act’s focus on cooperative viability gives NORDECO a statutory foothold, but weak enforcement dilutes its punch.

III. Procedural Red Flags: Did Congress Cut Corners?

Lack of Consultation (EPIRA Sec. 37, Local Govt Code Sec. 27)

EPIRA’s Sec. 37 requires public hearings for power sector reforms, ensuring stakeholder input. The Local Government Code (Sec. 27) mandates consultation with affected communities for projects impacting them. NORDECO claims it was blindsided—no meaningful hearings involved its 80,000+ member-consumers or local officials in Davao del Norte and Davao de Oro. News reports (e.g., MindaNews, Apr. 10, 2025) echo this, noting “no proper consultation.”

Counterpoint: House and Senate records show deliberations (HB 11072, SB 2888), but their depth is unclear. If consultations were perfunctory, Province of North Cotabato v. GRP (G.R. No. 183591, 2008) warns against legislative overreach sans stakeholder buy-in. This is NORDECO’s strongest procedural jab.

ERC Bypassed (EPIRA Sec. 43)

The Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) oversees distribution utilities under EPIRA Sec. 43, including franchise disputes and performance audits. NORDECO argues Congress usurped ERC’s role by legislating a franchise transfer without technical evaluation—did NORDECO’s outages justify ousting it? Mactan Electric upheld ERC’s authority to assess utility efficiency, suggesting Congress should’ve deferred to regulators.

But: Congress’s plenary power over franchises (Art. XII, Sec. 11) trumps ERC’s mandate. Still, bypassing ERC risks perceptions of political favoritism, especially with Aboitiz’s clout.

Presidential Inaction’s Shadow

Marcos’s failure to sign RA 12144, letting it lapse into law, raises eyebrows. While constitutionally valid, it fuels NORDECO’s narrative of a rushed process lacking executive buy-in. SunStar (Apr. 11, 2025) notes NORDECO saw this as echoing Marcos’s 2022 veto of a similar bill. Legally, it’s a non-issue, but politically, it paints RA 12144 as a law nobody fully owns.

IV. The Road Ahead: Litigation Landmines and Fixes

Litigation Risks and Injunction Odds

NORDECO’s planned petition for a temporary restraining order (TRO) rests on irreparable harm—80,000 households face potential rate hikes and service disruptions under Davao Light. NEA v. COA supports cooperative autonomy, bolstering a TRO bid. Grounds include:

- Due Process Violation: Franchise revocation sans hearing.

- Statutory Breach: PD 269 and NEA Reform Act protections ignored.

- Procedural Lapse: No consultation per EPIRA and Local Govt Code.

G.R. No. 264260 hurts NORDECO by affirming non-exclusivity, but Mactan Electric‘s pro-efficiency bias favors Davao Light only if consumer gains are proven. Province of North Cotabato could tip scales if courts see legislative overreach.

Likelihood of TRO: 60%—courts may pause RA 12144 to scrutinize process, but overturning it outright is tougher (40% chance). Davao Light’s data (209-minute brownouts) and consumer support weaken NORDECO’s “harm” claim long-term.

Policy Fixes to Avoid a Sequel

RA 12144’s fallout demands reforms to prevent franchise wars:

- For NORDECO: File a TRO citing procedural flaws and rural harm. Rally member-consumers to amplify public pressure.

- For Congress: Amend RA 12144 to include:

- Transition Safeguards: Retain NORDECO employees, freeze rates for two years.

- Buy-In Clause: Compensate NORDECO for lost areas, per PD 269’s intent.

- ERC Oversight: Mandate regulatory review before franchise shifts.

- For Courts: Post-G.R. No. 264260, clarify franchise exclusivity for cooperatives. Are they property rights or revocable privileges? A definitive ruling would curb future chaos.

Conclusion: A Spark That Could Ignite a Legal Inferno

RA 12144 isn’t just a franchise reshuffle—it’s a test of constitutional limits, statutory integrity, and procedural fairness. NORDECO’s fight channels the underdog spirit of rural cooperatives, but Davao Light’s efficiency edge and consumer backing make this no slam dunk. The Supreme Court looms as the ultimate arbiter, with G.R. No. 264260 casting a long shadow. For now, RA 12144 stands, but its shaky foundations—spotty consultation, statutory tension, and rural risks—could topple it if courts dig deep. Kweba ng Katarungan will keep watching, ready to call out the next blackout in this high-voltage saga. Who’s got the real power? Stay tuned.

Disclaimer: This is legal jazz, not gospel. It’s all about interpretation, not absolutes. So, listen closely, but don’t take it as the final word.

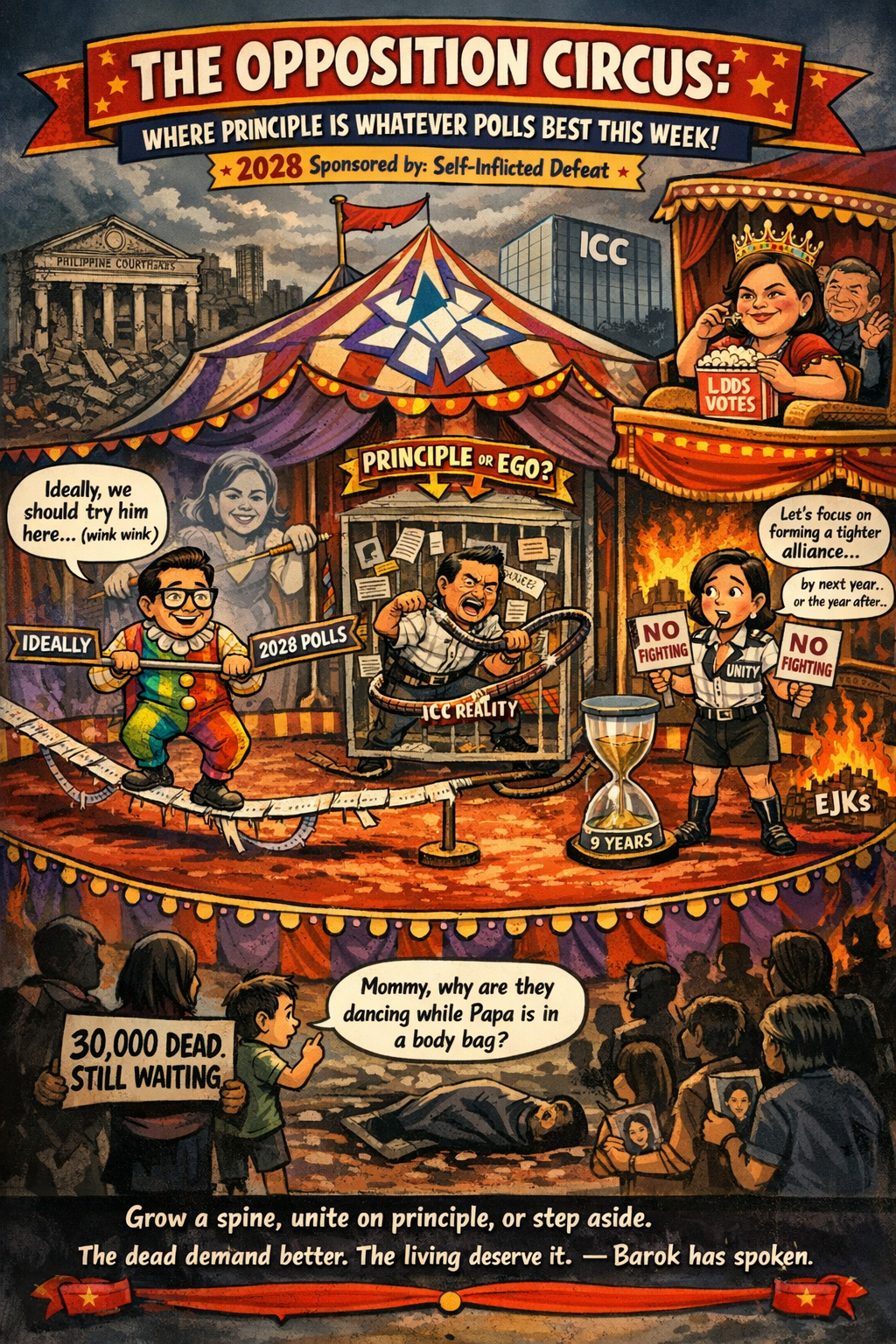

- Bam Aquino’s “Ideally Local” EJK Fantasy vs Trillanes’ ICC Reality – Why the Opposition Is Handing 2028 to Sara Duterte

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

- From “Never Again” to “Ideally Here”: How Bam Aquino Defended the Impunity Machine

- From Diverticulitis to Detention: How a Fake CT Scan Landed Critics in the NBI Crosshairs

- Marcos’ “Teachers First” Mirage: ₱10,000 Allowance or Just Another Vote-Buying Photo-Op?

- Dizon’s Maharlika Highway Exclusive Club: Only Billion-Peso Boys Allowed (Small Contractors Need Not Apply)

- 2028 Elections Just Got Bloodier: Sara Declares War on Marcos While Impeachment Complaints Line Up Like Jeepneys in EDSA

- From Barangay Captain to Cabinet: Why 73% of Filipinos Think Bribery Is the Only Government Service That Actually Works

- Why Duterte Got the Fast-Track to The Hague but Bato & Bong Go Deserve a Full Constitutional Pageant

- Marcoleta’s Treason Fantasy: Why Charging Carpio for Peacetime “Betrayal” Is the Dumbest Thing You’ll Read This Week

- DOJ Caught Shielding Alleged Rapist Because He’s Their Sabungeros Golden Boy? The Ugly Truth Exposed

- PNP “Integrity Reforms”: Nartatez’s ICC Panic Button or Just Another Camp Crame Comedy Special?

Leave a comment