By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — April 20, 2025

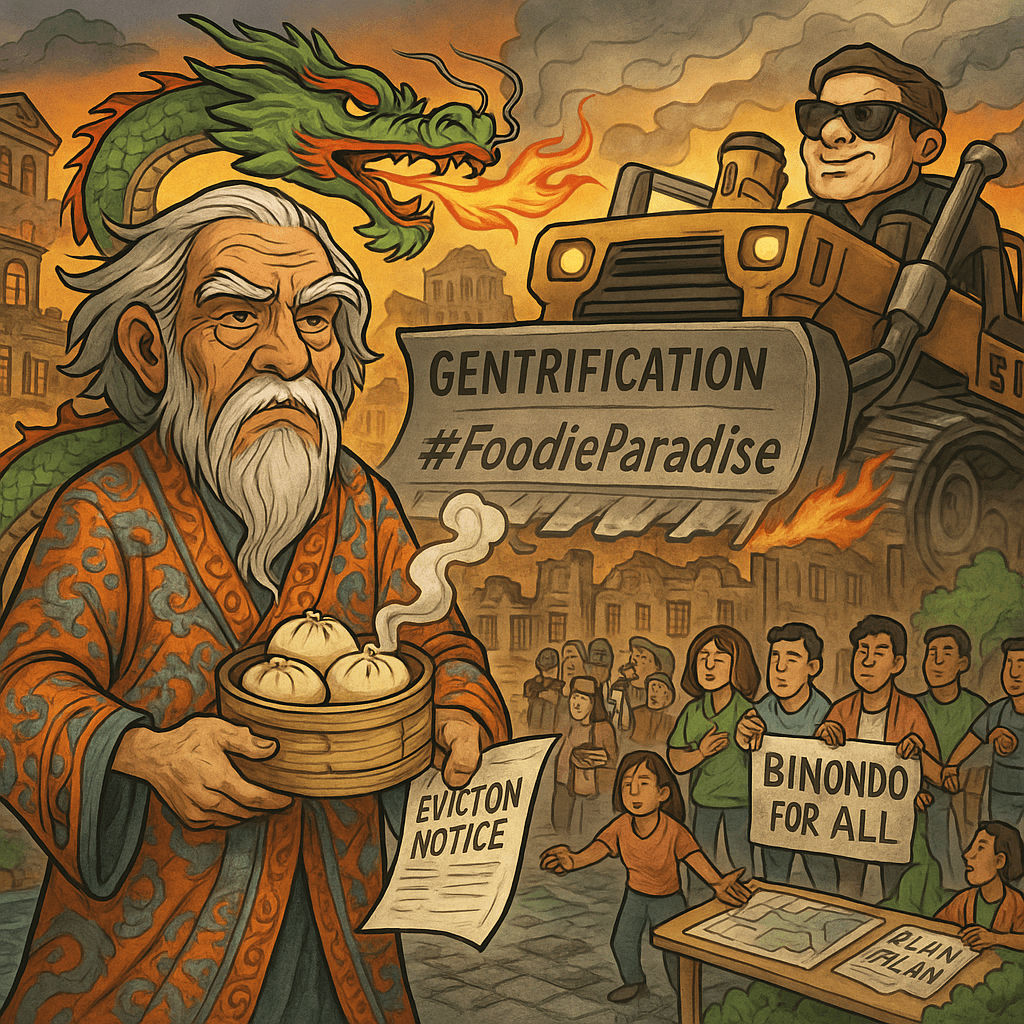

Ongpin Street hums at dawn, siopao steam mingling with vendor chatter as Lunar New Year nears. Yet in a shadowed alley, an eviction notice flaps on a shophouse, a grim omen for Binondo, the world’s oldest Chinatown. Will its vibrant heritage survive, or will progress bulldoze the stories carved in its streets?

A Legacy Forged in Fire and Fusion

Binondo, born in 1594 under Spanish rule, isn’t just Manila’s Chinatown—it’s a 400-year epic of survival. Crafted as a haven for Christian-converted Chinese traders, it wove a tapestry of cultures: Taoist temples rise beside the Minor Basilica of San Lorenzo Ruiz, founded in 1596, a church that endured British bombardment in 1762, earthquakes, and World War II’s ruin. Hokkien-named streets echo the Chinese-Filipino merchants who married locals, building a community that thrived through chaos.

Once, Escolta Street pulsed as the “Wall Street of the Philippines,” a pre-WWII financial powerhouse. War shattered its grandeur, scattering businesses, but Binondo’s entrepreneurial fire never dimmed. Today, Ongpin Street sparkles as the “jewelry capital,” while Lucky Chinatown Mall lures shoppers with sleek galleries and a museum tracing Binondo’s saga. Forget the tired stereotypes of Chinatowns as seedy underworlds—rooted in xenophobia. Binondo dazzles, its sacred spaces, street art, and pancit aromas weaving a multicultural marvel.

The High Stakes of a Chinatown Under Siege

Binondo’s fame as a foodie mecca, with its “Binondo Food Crawl” and legendary panciterias like Toho Antigua (est. 1888), draws crowds—nearly 200,000 for Lunar New Year 2025, per reports. But this spotlight fuels fierce tensions threatening its essence.

- Gentrification’s Ruthless March: Chic cafes like Apologue Coffee, pouring Pei Pa Koa lattes, and luxury condos by Megaworld herald a new Binondo. Land values soar—up to $10,000 per square meter—fueled by cultural allure and prime location. Yet 37% of Metro Manila’s people live in slums, many on Binondo’s edges, facing eviction as rents spike. This mirrors global Chinatowns, from San Francisco to Bangkok, where heritage bows to wealth.

- Heritage Reduced to a Hashtag: The “foodie” hype celebrates siopao and dim sum but risks turning Binondo into a tourist trap. Culinary tours spotlight Shanghai Fried Siopao or Wai Ying’s dumplings, yet often gloss over the colonial struggles and wartime scars that forged this community. Is Binondo’s soul being sold for Instagram likes?

- Who Profits from the Boom? Escolta’s fall from financial titan to faded relic contrasts with Binondo’s real estate frenzy. Tycoons like Federal Land’s backers cash in, but do working-class vendors, heirs of early settlers, see the wealth? Studies warn of “accumulation by dispossession,” where development ousts the poor, deepening Manila’s inequality.

Voices Rising from the Heart of Binondo

To grasp Binondo’s pulse, I met Maria Lim, 62, whose family has run Eng Bee Tin, a cherished panciteria and bakery, since 1912. Her Fujianese great-grandfather blended Hokkien recipes with Filipino flair. “This shop is our roots,” she says, pointing to ancestral photos amid hopia stacks. But rents, up 20% in two years, threaten her lease. “Tourists crave our siopao, but will we survive for them?”

At the First United Building, a 1928 art-deco jewel, artist collectives defy erasure. Jomar, a 28-year-old muralist, shows me HUB: Make Lab, a creative incubator. “Our art tells Binondo’s truths—migration, grit,” he says. The building’s Community Museum, honoring tycoon Sy Lian Teng, is a grassroots triumph. Yet Jomar fears condos swallowing Escolta will exile artists. “Heritage isn’t just stone; it’s us.”

Near the Pasig River, El Hogar, a 1914 skyscraper saved from demolition in 2014, stands hauntingly empty. Its art-deco splendor fades, with whispers of a boutique hotel conversion—a “preservation” that may lock out locals. These struggles echo in Bangkok’s Yaowarat, where vendors face eviction, or San Francisco’s Chinatown, where rents choke families. Binondo’s battle is a global cry.

Fighting for a Future That Honors the Past

Binondo’s preservation wins, like saving El Hogar or reimagining the First United Building, spark hope. Community efforts, like the People’s Plan securing social housing since the 1960s, offer a blueprint. But 400-year-old infrastructure crumbles, and Manila’s government often favors developers over residents.

Change is urgent. Heritage zoning, as in Singapore’s Chinatown, could shield historic sites while allowing smart growth. Community land trusts, tested in New York, would let residents own land collectively, halting displacement. Rent caps in historic zones could protect vendors like Maria Lim. Binondo’s $50 million annual tourism haul could fund affordable housing, not just glossy malls.

Advocacy groups, allied with local leaders, push a “Binondo for All” vision, demanding anti-displacement policies and infrastructure upgrades. Their victory depends on political courage. Manila must see Binondo as a cultural cornerstone, not a developer’s jackpot.

A Global Chinatown on the Brink

Binondo’s struggle mirrors a worldwide drama. In San Francisco, Chinatown resists tech-fueled gentrification; in Bangkok, vendors battle skyscrapers. These diaspora sanctuaries, forged by migration and tenacity, face one question: Can progress cherish history? Binondo’s path demands bold moves—zoning, trusts, policies prioritizing people. Without them, Ongpin’s siopao steam may vanish, and with it, a 400-year legacy.

Let’s champion Binondo, not as a photo-op but as a living home. Its saga—of resilience, fusion, survival—must endure. Manila’s leaders, and all who treasure its streets, must act before eviction notices claim victory.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment