By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — May 1, 2025

Introduction: A Mother’s Fight, A Nation’s Peril

In a dim Manila tenement, Josefa Carlos tallies coins to feed her children. Her husband, an overseas filipino worker (OFW) in Qatar, wires $500 monthly, but a ravenous peso—weakened by economic mismanagement—swallows most. “We ration rice to afford medicine,” she whispers, her resolve masking despair. Josefa’s struggle mirrors the Philippines’ plunge from a $238 million BOP surplus in Q1 2024 to a $3 billion deficit in Q1 2025, a $3.2 billion nosedive. This isn’t abstract economics—it’s a nation’s lifeblood draining, fueled by reckless borrowing and import obsession. Can the Philippines defuse this crisis before it engulfs millions like Josefa?

Shattered Illusions: A Deficit’s Deadly Surge

The $3.2 billion BOP reversal screams urgency, echoing past traumas. The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis saw a $2.4 billion deficit (about $4 billion today), sparked by currency collapses. The 2008 Global Recession delivered a $1.8 billion hit, softened by OFW remittances. Today’s deficit, while not the deepest, stings for its velocity and fragility—global trade wobbles, and the Philippines lags peers like Vietnam.

Debt servicing is the first culprit, siphoning reserves to pay P16.31 trillion ($280 billion) in sovereign debt by January 2025. Are these loans building schools or propping up budgets? Too often, they fund projects with uncertain returns, like infrastructure tied to well-connected firms. Then there’s the trade deficit, a gaping $5.09 billion in January 2025, rooted in importing rice and gadgets while exporting raw nickel. The human cost is brutal: a peso at P58.375 to $1 (from P57.847) inflates food prices, forcing families like Josefa’s to skip meals. Debt payments, now 20% of the budget (up from 15% in 2022), starve hospitals, pushing poverty—already 18%—toward a cliff.

Marcos Administration’s Optimism: A Disconnect with Reality

The Marcos administration calls this a “calm before the storm,” but their upbeat tone contrasts with the BSP’s grim forecast: a $4 billion deficit for 2025. President Marcos emphasizes remittances ($33 billion yearly) and FDI ($8 billion in 2024) as economic anchors, yet these are fragile supports. Remittances reflect OFW labor abroad, not domestic strength; FDI could falter if deficits erode confidence.

Transparency remains a challenge. The Treasury reports debt totals but omits terms—commercial or concessional? IMF and World Bank warnings highlight risks: a 61% debt-to-GDP ratio nears Greece’s pre-crisis 65%. Questions linger about China’s Belt and Road loans, with unclear repayment structures. Concerns also arise about infrastructure projects, where contracts often favor established firms, raising questions about equitable allocation of public funds.

Asia’s Warning Signs: Trapped in a Global Vice

Vietnam’s $10 billion trade surplus, built on electronics and factories, shames the Philippines’ reliance on call centers and ores. Vietnam invested in skills; the Philippines didn’t. Sri Lanka’s 2022 default—$51 billion in debt, empty reserves—ignited 50% inflation and riots. The Philippines isn’t there, but its debt-reserve slide whispers danger.

Geopolitics tightens the noose. U.S.-China trade clashes disrupt Philippine electronics exports (20% of total). China’s South China Sea aggression could spike shipping costs. The U.S., despite alliance, may slap tariffs, costing $1 billion in exports. Caught in this superpower tug-of-war, the Philippines risks becoming a pawn.

Defusing the Volcano: A Race Against Time

Urgent steps are vital. BSP rate hikes could brace the peso, but at 6.5%, they’d strangle growth (6% in 2025). Instead, diaspora bonds could raise $5–10 billion from OFWs, mimicking India’s 1990s success. Long-term, a South Korea-style industrial push—subsidizing tech, mandating exports—could slash import reliance. Nueva Ecija’s rice cooperatives, boosting yields 30%, prove local ingenuity can curb food imports. Debt restructuring is non-negotiable: IMF grace periods or 1% refinanced loans could save $10 billion, funding schools and clinics.

Closing: The Eruption Is Now

Josefa Carlos doesn’t parse BSP data, but she bears its scars. Her family’s sacrifices prop a nation borrowing against its children’s future. The Philippines faces a choice: Greece’s austerity nightmare or a bold pivot to reform. Marcos must lead—prioritizing transparency over optimism, action over promises. The volcano is erupting. But unlike natural disasters, this catastrophe is man-made—and can be undone, if leaders act before the ash buries us all.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

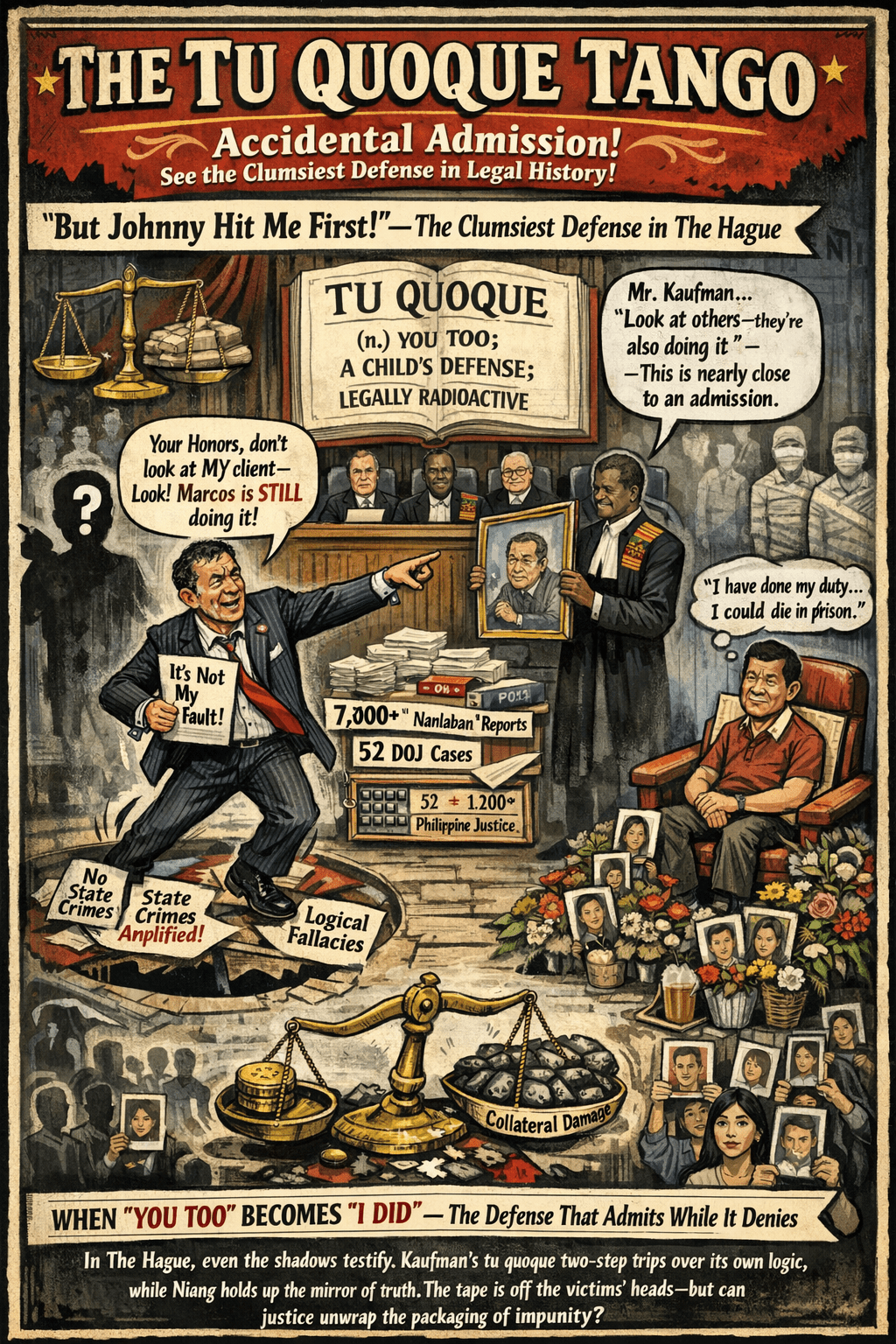

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment