By Louis ‘Barok’ C Biraogo — May 3, 2025

WHEN a veteran columnist accuses a congressman of bribery in a high-stakes impeachment, sparks fly. When the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) slaps that columnist with cyberlibel charges, it’s less a spark and more a five-alarm fire. The case against Roberto Tiglao, filed by NBI-7 at the behest of Deputy Speaker Duke Frasco, is a legal and political powder keg. Tiglao’s February 14, 2025, column alleged Frasco and 239 lawmakers took bribes to impeach Vice President Sara Duterte. Frasco cried foul, and NBI-7 pounced with cyberlibel charges under the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012. Is this a textbook case of defamation or a brazen attempt to muzzle the press? Let’s dissect it with the precision of a Supreme Court ponencia and the skepticism of a jaded legal blogger.

The Law: Cyberlibel’s Sharp Edges

Cyberlibel in the Philippines is a beast born of two statutes: Article 355 of the Revised Penal Code (RPC), which defines traditional libel, and Section 4(c)(4) of Republic Act 10175, which extends libel to cyberspace. Article 355 punishes “public and malicious imputation of a crime” with prisión correccional or a fine up to PHP 6,000. RA 10175 amplifies this, applying libel’s penalties to defamatory statements made via “Information and Communications Technology.” The Supreme Court upheld cyberlibel’s constitutionality in Disini v. Secretary of Justice (G.R. No. 203335, 2014), but cautioned that it must not unduly restrict free speech.

To convict Tiglao, the prosecution must prove the four-part test for cyberlibel: (1) defamatory imputation, (2) malice, (3) publication via ICT, and (4) identifiability of the victim. Let’s apply it:

- Defamatory Imputation: Tiglao’s piece, “Cebu rep details how impeachment bribery worked,” accuses Frasco of accepting bribes to vote for Duterte’s impeachment. Alleging a crime like bribery is textbook defamation under RPC Article 353—it tends to “blacken the honor or reputation” of Frasco. Strike one.

- Malice: This is where the case gets thorny. For public figures like Frasco, proving malice demands evidence of “actual malice”—knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard for the truth—as reaffirmed in Michael C. Guy v. Raffy Tulfo, et al. (G.R. No. 213023, 2019) and Borjal v. Court of Appeals (G.R. No. 126466, 1999), which draw on the New York Times v. Sullivan standard. Tiglao claims he relied on Frasco’s video and a news report, which, if plausibly suggestive of bribery, could undermine the malice element. In the cyberlibel context, Disini v. Secretary of Justice (G.R. No. 203335, 2014) further underscores the need for precision in applying this standard to online defamation. Proving Tiglao acted with reckless disregard won’t be a walk in the park.

- Publication via ICT: No contest. The article appeared on Tiglao’s website and The Manila Times’ digital platform. Published, check.

- Identifiability: Frasco is named explicitly. No hiding here.

Prima facie, the elements align, but Tiglao’s defenses could derail the case. The law’s clarity contrasts with the case’s political murkiness.

The Facts: Tiglao’s Pen vs. Frasco’s Pride

Tiglao’s February 14, 2025, column, published in The Manila Times and on his website, cited a video where Frasco allegedly admitted voting for Duterte’s impeachment out of fear of losing project funds. Frasco filed a complaint on March 19, 2025, calling the claim “reckless” and baseless (Cebu Daily News). NBI-7 filed charges on April 25, 2025, alleging Tiglao’s piece was “malicious” and lacked evidence (SunStar Cebu).

Tiglao’s defense is twofold. First, he argues good faith under RPC Article 354, which presumes lawful intent for “fair and true” reports on public acts. His reliance on Frasco’s video and a news report could bolster this, but only if the sources reasonably supported his bribery claim. Second, he invokes privileged communication, citing Borjal v. Court of Appeals (G.R. No. 126466, 1999), which protects opinions on public officials’ conduct unless proven malicious. The line between fact and opinion is blurry—Tiglao’s piece reads like a factual exposé, not a hedged editorial. If courts see it as a statement of fact, Borjal won’t save him.

Procedurally, NBI-7’s handling raises red flags. Tiglao claims he was subpoenaed but not given Frasco’s complaint, calling the process a “formality” (Cebu Daily News). This opacity smells like a violation of due process under the Rules of Court, Rule 112, which mandates transparency in preliminary investigations. If NBI-7 stonewalled Tiglao, it’s a misstep that could taint the case’s legitimacy.

The Politics: Impeachment Games and Press Freedom

The case’s political backdrop is a circus. Duterte’s impeachment was a lightning rod, pitting her allies against House Speaker Martin Romualdez’s faction. Tiglao’s claim that Frasco’s vote was bought isn’t far-fetched—past impeachments, like Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno’s ouster in 2018, were rife with allegations of political horse-trading (Rappler). Frasco’s video, where he reportedly tied his vote to project funds, fuels suspicion. In a House where loyalty often follows funding, Tiglao’s accusation lands in plausible territory.

But plausibility isn’t proof, and Frasco’s cyberlibel suit raises a bigger question: is this a weapon to silence critics? The Philippines’ cyberlibel law has a checkered history of chilling speech. The 2020 conviction of Maria Ressa and Reynaldo Santos in People of the Philippines v. Maria Ressa and Reynaldo Santos Jr. (R-MNL-19-01141-CR) drew global condemnation for targeting press freedom (Global Freedom of Expression ). Frasco, a public figure, enjoys less protection against criticism, but his swift resort to cyberlibel—backed by NBI-7’s haste—smells like political theater. The law’s use here risks deterring journalists from probing power, especially when impeachment stakes are sky-high.

Why This Matters: Ethics, Media, and the Public Figure Doctrine

The Manila Times’ apology on February 19, 2025, is a gut punch to Tiglao’s defense (SunStar Cebu). By admitting the article was “unverified” and caused harm, the paper undercuts Tiglao’s claim of good faith. Under the SPJ Code of Ethics, journalists must verify information and minimize harm. Tiglao’s piece, fact-checked as dubious by VERA Files, flirts with ethical recklessness. The apology suggests The Manila Times saw liability looming, leaving Tiglao to fend for himself.

Frasco’s status as a lawmaker invokes the public figure doctrine. In [Guy v. Tulfo], the Supreme Court held public officials must prove actual malice to win defamation cases, a high bar rooted in New York Times v. Sullivan. Frasco’s complaint hinges on Tiglao’s “malicious” intent, but proving Tiglao knew his claims were false—or didn’t care—is a steep climb. The video’s content, if suggestive of coercion, could give Tiglao enough cover to dodge malice.

This case isn’t just about Tiglao and Frasco—it’s a litmus test for Philippine press freedom. Cyberlibel’s broad reach, coupled with political heavyweights wielding it, threatens to shrink the space for critical journalism. The NBI’s role as Frasco’s enforcer only deepens the chill. If Tiglao’s piece was sloppy, he deserves scrutiny, but using cyberlibel to settle political scores sets a dangerous precedent.

Conclusion: A Tightrope Between Truth and Power

Tiglao’s cyberlibel case teeters on a knife’s edge. Legally, the prosecution has a strong prima facie case, but malice is a hurdle, and Tiglao’s good-faith defense could hold water if his sources check out. Politically, the case reeks of retaliation, echoing the weaponization of libel seen in People v. Ressa (R-MNL-19-01141-CR). Ethically, The Manila Times’ apology and Tiglao’s spotty track record weaken his moral high ground. NBI-7’s procedural fumbles add fuel to the fire, suggesting a rush to please a powerful complainant.

For lawyers, this is a masterclass in cyberlibel’s complexities. For journalists, it’s a warning: tread carefully when poking power. For policymakers, it’s a call to rethink a law that too easily becomes a cudgel. Tiglao may have swung hard, but Frasco’s counterpunch risks knocking out more than just one columnist—it threatens the Fourth Estate itself.

Disclaimer: This is legal jazz, not gospel. It’s all about interpretation, not absolutes. So, listen closely, but don’t take it as the final word.

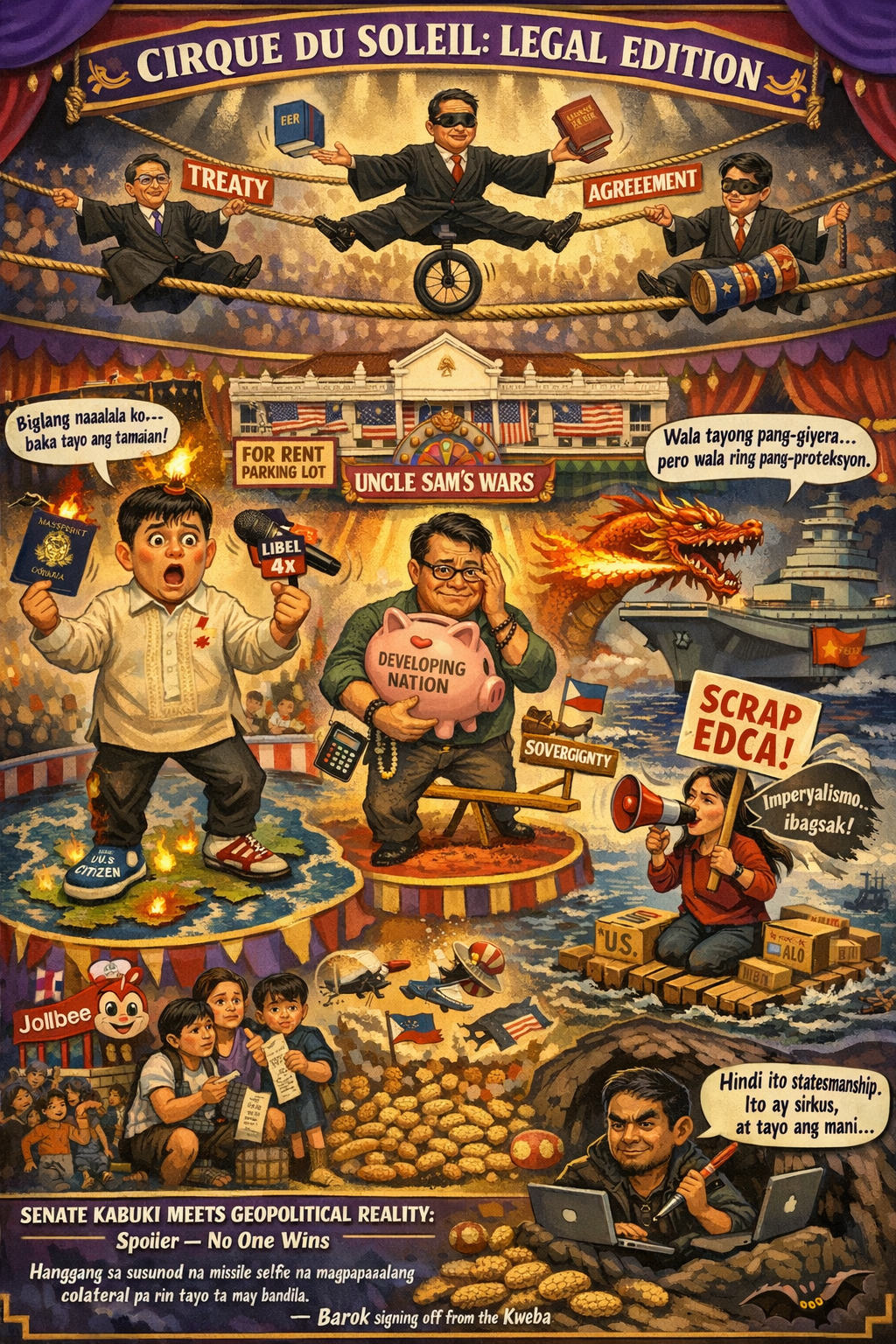

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

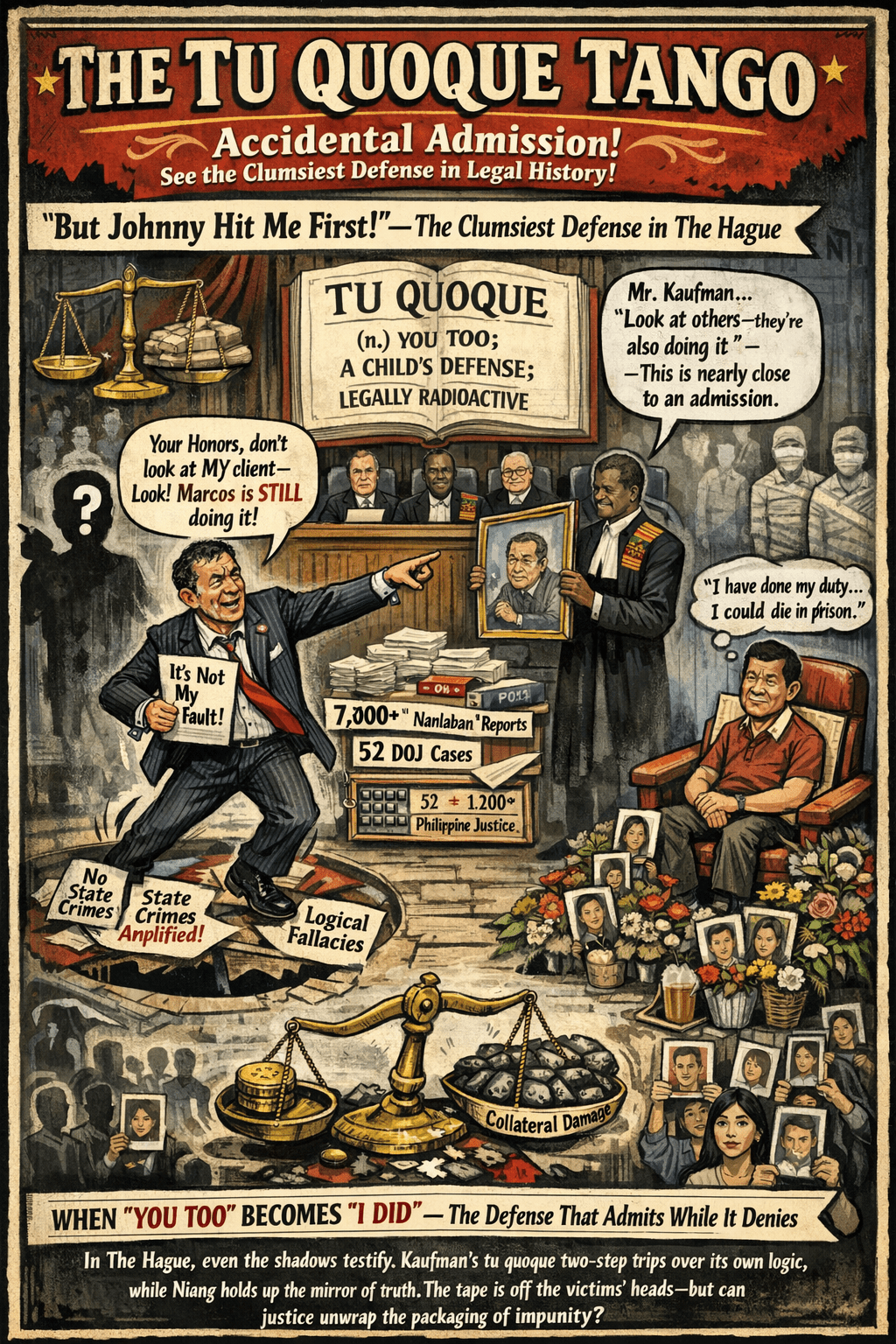

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment