By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — May 7, 2025

THE Philippine National Police’s (PNP) rapid-fire prosecution of a Davao vlogger for falsely alleging a police raid on former President Rodrigo Duterte’s home is a legal powder keg. Charged under the antiquated Article 154 of the Revised Penal Code (RPC) and amplified by the Cybercrime Prevention Act (RA 10175), the case—filed days after the PNP’s Anti-Fake News Committee launch—smells of political maneuvering amid Duterte’s International Criminal Court (ICC) drama. This analysis tears apart the prosecution’s arguments, the vlogger’s defenses, and the chilling implications for free speech in a Philippines where “fake news” is a loaded weapon against dissent.

I. The Spark: A Vlogger’s Claim Ignites a Firestorm

Case Snapshot

On May 1, 2025, a Davao-based male vlogger posted online that 30 Criminal Investigation and Detection Group (CIDG) and 90 Special Action Force (SAF) personnel “from Luzon” raided Duterte’s residence on April 30. The PNP’s Anti-Cybercrime Group labeled the claim “fabricated,” alleging intentional disinformation. By May 6, 2025, Police Regional Office 11 (PRO 11) charged the vlogger under Article 154 RPC (Unlawful Use of Means of Publication) in relation to Section 6 of RA 10175, which escalates penalties for cybercrimes. The PNP withheld the vlogger’s identity, noting his 218,000 subscribers and 20 million views since May 2020 (Inquirer News, The Global Filipino Magazine).

The PNP’s immediate denial, led by CIDG Director Maj. Gen. Nicolas Torre III, confirmed no such operation occurred (Brigada News). This case is a flagship action for the PNP’s Joint Anti-Fake News Action Committee (JAFNAC), launched May 2, 2025, to tackle disinformation (Philippine News Agency).

Political Tinderbox

The case erupts amid a volatile political climate. Duterte, arrested on March 11, 2025, and transferred to The Hague for ICC proceedings over alleged drug war crimes, remains a lightning rod (BBC News). His supporters, rallied by a March 28, 2025, birthday event in Davao, see such legal moves as assaults on his legacy (Reuters). The vlogger’s claim, amplified by his massive online reach, risked sparking unrest, especially with reports of pro-Duterte vloggers facing similar scrutiny (Rappler, March 21, 2025). The PNP’s swift action and secrecy around the vlogger’s identity raise red flags about selective enforcement in a nation where disinformation often serves power.

II. Legal Showdown: Prosecutors vs. the Vlogger

Prosecution’s Arsenal: Building a Case

Primary Weapon: Article 154 RPC and RA 10175

Article 154 RPC criminalizes publishing “false news which may endanger the public order, or cause damage to the interest or credit of the State.” Penalties include arresto mayor (1 month to 6 months imprisonment) and fines from PHP 200 to 2,000, adjusted by RA 10951. Section 6 of RA 10175 escalates penalties for RPC crimes committed via ICT, potentially to prision correccional (6 months to 6 years). The PNP alleges the vlogger’s online post falsely reported a raid, risking disorder in a politically charged Philippines (Philippine News Agency).

Backup Charges: Expanding the Attack

The prosecution could pursue:

- Cyber Libel (RA 10175, Section 4(c)(4)): If the post defamed PNP officers or Duterte, this applies, but the focus on public order prioritizes Article 154.

- Alarm and Scandal (RPC, Article 155): Causing public alarm carries arresto menor (1 to 30 days) or fines up to PHP 200. The post’s potential to incite panic among Duterte supporters could trigger this, but evidence of actual disturbance is thin.

- Inciting to Sedition (RPC, Article 142): This requires intent to incite rebellion. Without evidence of the vlogger urging action, this charge is a long shot.

Proving the Case: The Prosecution’s Burden

The prosecution must prove three elements for Article 154, as derived from the statute and reinforced by cases like Chavez v. Gonzales (G.R. No. 168338, February 15, 2008), which addressed harmful speech:

- Falsity: The PNP’s denial and Anti-Cybercrime Group’s “fabricated” finding establish this (Inquirer News).

- Publication: The vlogger’s post, viewed by 218,000 subscribers, meets this requirement.

- Potential to Endanger Public Order: Article 154’s “may endanger” standard requires only a likelihood of disorder. Duterte’s influence and supporter gatherings on April 30 (Sunstar) make this plausible.

In Chavez v. Gonzales, the Supreme Court emphasized that speech posing a clear and present danger to public order can be regulated, strengthening the prosecution’s case here.

The Vlogger’s Counterattack: Defense Strategies

Claiming Truth: A Shaky Shield

The vlogger could argue he believed the raid report was true, negating malice under Article 154. However, the PNP’s denial and “fabrication” claim demand credible evidence (e.g., a source), which seems unlikely (Newsweek, Inc. v. IAC, G.R. No. L-67608, September 20, 1985).

Free Speech: Waving the Constitutional Flag

Article III, Section 4 of the 1987 Constitution protects free speech and press. The vlogger could argue Article 154 violates this, but Gonzales v. COMELEC (G.R. No. L-27833, April 18, 1969) permits restrictions under the “clear and present danger” test. A false raid claim, amid Duterte’s ICC arrest, likely meets this standard, hobbling the defense.

Overbreadth: Attacking the Law’s Vagueness

The vlogger might challenge Article 154 as unconstitutionally vague, arguing its “may endanger” language chills legitimate speech. While Philippine courts have upheld restrictions on harmful speech (Chavez v. Gonzales), international cases like Chakrabarti v. Union of India (India, 2018) highlight risks of overbroad disinformation laws. This argument faces an uphill battle in local courts.

Procedural Jabs: Questioning the Process

The vlogger could scrutinize the PNP’s evidence (e.g., how “fabrication” was determined) or jurisdiction. However, RA 10175’s broad scope and the Anti-Cybercrime Group’s expertise likely neutralize this defense absent clear irregularities.

III. Political Chess and Ethical Quagmires

Disinformation or Dissent? A Dangerous Blur

The state’s fight against disinformation is valid in a social media-saturated Philippines, where false narratives spread like wildfire (Reuters). Yet, prosecuting a vlogger for one post risks equating disinformation with dissent, especially given Duterte’s ICC troubles and the Marcos-Duterte rift (BBC News). The PNP’s JAFNAC, billed as a neutral tool, could morph into a weapon against critics, mirroring global trends of disinformation laws curbing speech.

Selective Justice? The PNP’s Double Standards

The PNP’s focus on this vlogger contrasts with leniency toward pro-Duterte vloggers, some of whom apologized for fake news without charges (Rappler, March 21, 2025). This disparity fuels suspicions of political targeting, especially if the vlogger is a Duterte critic. Such selective enforcement undermines the PNP’s credibility and public trust.

Vloggers as Newsroom Rogues: Ethical Failings

The SPJ Code of Ethics demands verification, harm minimization, and accountability—standards vloggers should heed as quasi-journalists. The vlogger’s unverified raid claim flouts these principles, but the absence of influencer regulation creates an ethical void. Unlike traditional media, vloggers operate unchecked, amplifying their impact and responsibility.

IV. Charting the Path Forward: Recommendations

Judiciary: Guarding the Free Speech Line

Courts must rigorously scrutinize Article 154 cases, demanding clear evidence of public order risks and probing PNP motives, especially in Duterte’s shadow. Strict application prevents politicized prosecutions.

Legislators: Sharpening the Legal Blade

Amend RA 10175 to define “false news” narrowly, requiring intent and actual harm. This balances free speech with public order, mitigating chilling effects.

Media: Taming the Vlogger Wild West

Vloggers should adopt voluntary fact-checking, guided by the International Fact-Checking Network. Media outlets could collaborate with platforms to train influencers, fostering ethical content creation without heavy-handed laws.

V. Battle Lines Drawn: A Summary

| Aspect | Prosecution’s Strike | Vlogger’s Defense | Wider Stakes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Charge | Article 154 RPC + RA 10175: False news risking disorder. Bolstered by Chavez. | Truth defense flimsy; free speech curbed by “clear and present danger” (Gonzales). | Broad application threatens dissent. |

| Additional Charges | Cyber libel, alarm and scandal possible but secondary. | Procedural attacks likely futile. | Selective enforcement risks trust erosion. |

| Political Context | Duterte’s ICC case and Marcos feud heighten stakes. | Political motivation argument not legally viable. | JAFNAC could target critics unevenly. |

| Ethical Issues | Vlogger’s verification failure breaches SPJ Code. | Unregulated influencers dodge accountability. | Voluntary ethical standards needed. |

VI. The Verdict Awaits: A Nation on Edge

The Davao vlogger case lays bare the fraught intersection of disinformation, free speech, and political power in the Philippines. The prosecution’s case under Article 154 and RA 10175 is legally robust but politically charged, with defenses like truth and free speech facing steep hurdles. The broader danger is clear: without judicial caution and legislative reform, “fake news” laws could become tools to silence critics, fraying the democratic fabric of an already divided nation.

Key Citations

- PNP statements (Philippine News Agency),

- RA 10175,

- Chavez v. Gonzales (G.R. No. 168338, February 15, 2008),

- Gonzales v. COMELEC (G.R. No. L-27833, April 18, 1969)

Disclaimer: This is legal jazz, not gospel. It’s all about interpretation, not absolutes. So, listen closely, but don’t take it as the final word.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

- $2 Trillion by 2050? Manila’s Economic Fantasy Flimsier Than a Taho Cup

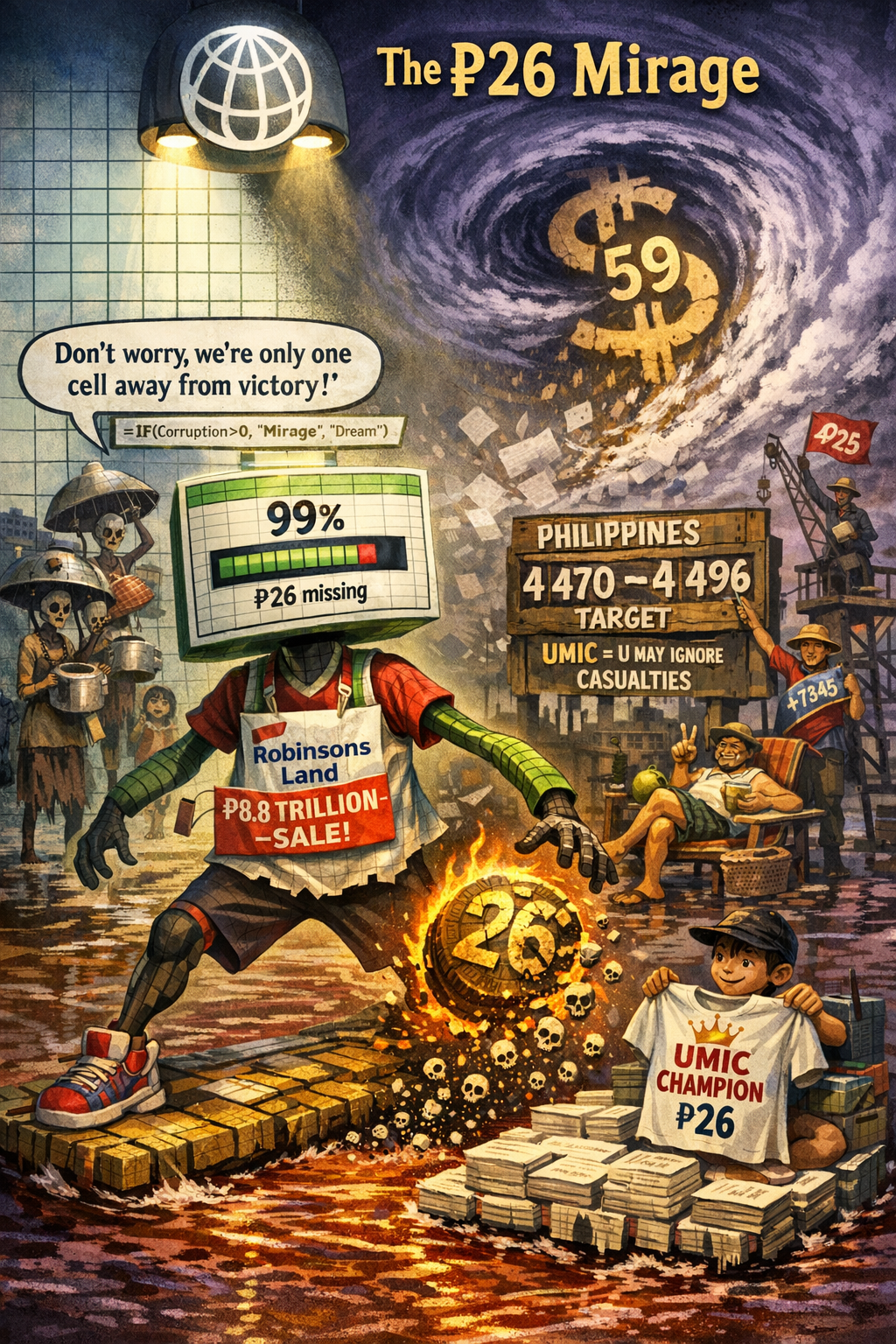

- $26 Short of Glory: The Philippines’ Economic Hunger Games Flop

Leave a comment