By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — May 9, 2025

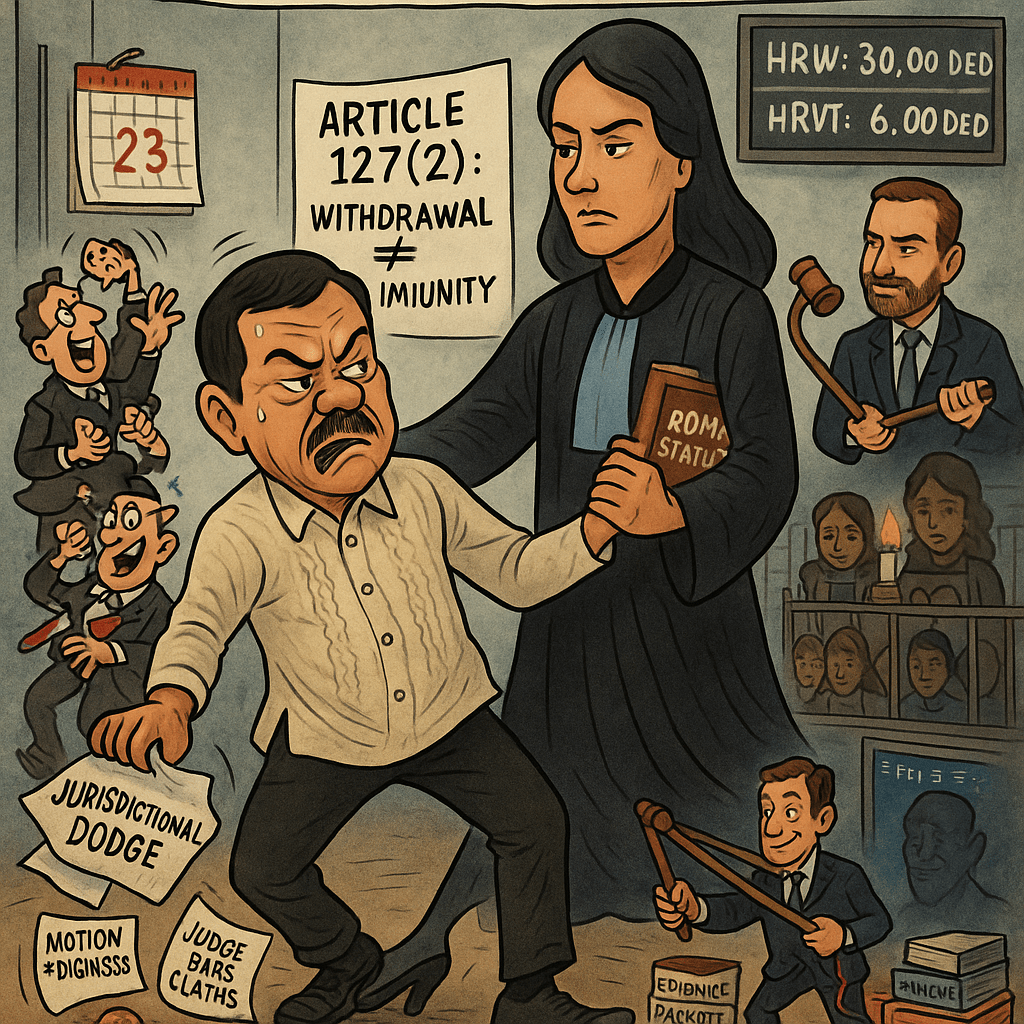

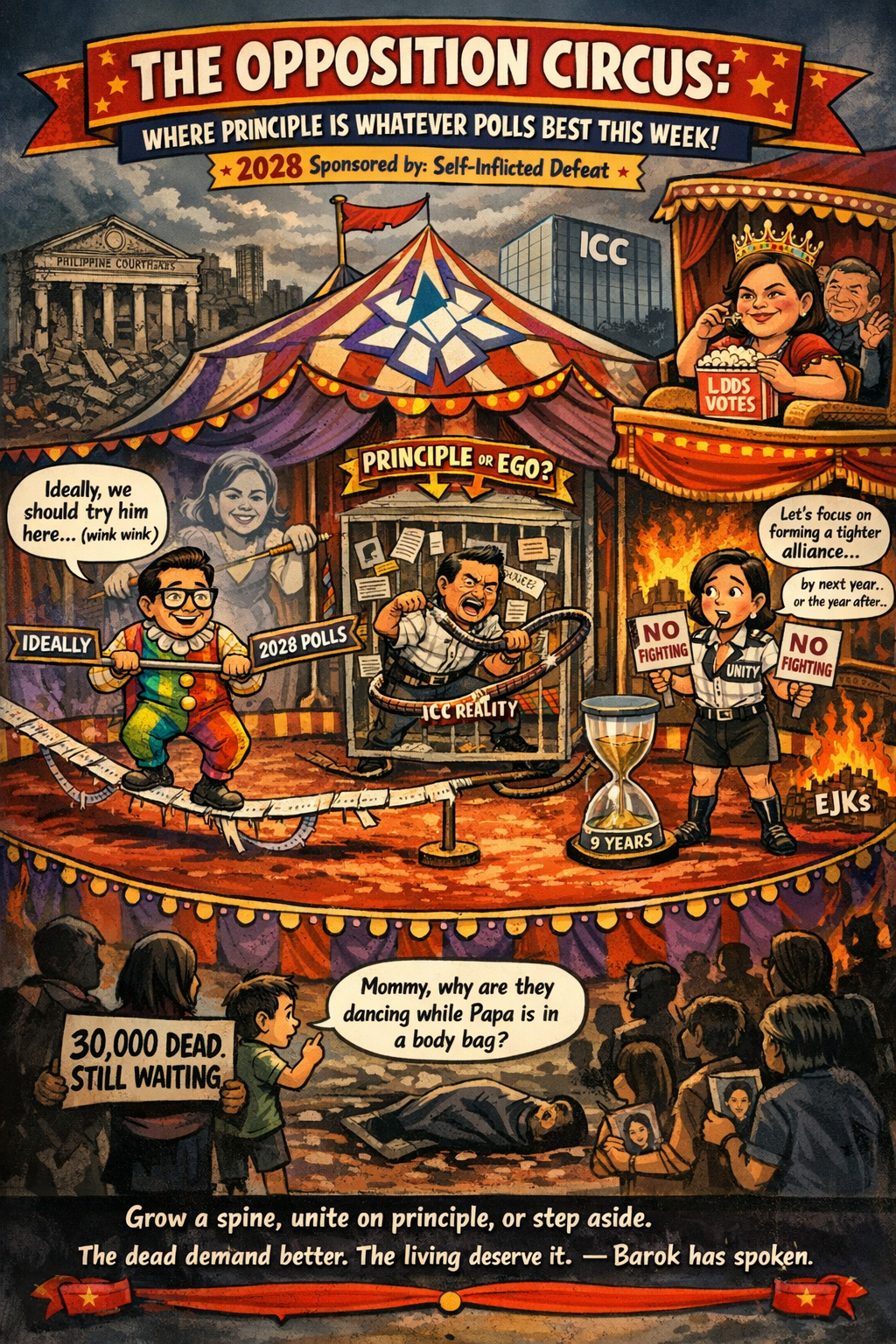

THE International Criminal Court’s case against former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte is a legal cage match where the defense’s procedural sleights-of-hand collide with the prosecution’s calculated evidence dump. Duterte’s lawyers, seemingly mistaking the ICC for a Manila traffic court, have doubled down on jurisdictional dodges and even tried to oust judges. Meanwhile, Prosecutor Karim Khan’s 139-item evidence barrage aims to pin Duterte for crimes against humanity tied to his blood-soaked drug war and the Davao Death Squad. As the September 23, 2025, confirmation hearing looms, the question isn’t whether the ICC can deliver justice—it’s whether it can slice through the defense’s fog of technicalities before the world tunes out.

Contextualizing the Bloodbath

Duterte faces charges of crimes against humanity, including murder, for at least 43 killings linked to the Davao Death Squad (DDS) during his tenure as Davao City mayor (2011–2016) and the extrajudicial slaughter of thousands in his presidency’s drug war (2016–2019). Human Rights Watch estimates up to 30,000 deaths, mostly small-time drug users, dwarfing Manila’s claim of 6,000. The ICC asserts jurisdiction under Article 12(2) of the Rome Statute, covering crimes on a state party’s territory—here, the Philippines, a member from 2011 until its 2019 withdrawal.

The Philippines’ exit, effective March 17, 2019, is the defense’s golden ticket. Duterte’s team argues the ICC lost authority post-withdrawal, but this jurisdictional Hail Mary is a house of cards, as Article 127(2) and ICC precedents make clear.

Jurisdictional Jujitsu: The Defense’s Grasping at Straws

Technicalities Over Truth

Duterte’s legal team, led by Nicholas Kaufman and Dov Jacobs, has leaned into procedural ploys with authoritarian flair. Their May 1, 2025, challenge to the ICC’s jurisdiction—claiming no authority post-withdrawal—is a recycled loser. Article 127(2) of the Rome Statute explicitly retains jurisdiction over crimes committed while a state was a party, as affirmed by the ICC’s March 7, 2025, arrest warrant covering 2011–2019 (ICC Philippines).

The defense’s misreading of Article 12(2)—insisting jurisdiction requires active state party status—is legally flimsy. The ICC’s Burundi precedent (2017) demolishes this, with the Court retaining authority over pre-withdrawal crimes (Burundi ICC). Then there’s the May 1, 2025, bid to remove two judges for alleged bias, swatted down on May 6 as procedurally baseless (GMA News). This mirrors tactics from Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir, whose team cried foul to stall genocide charges.

The Cost of Delay

These stunts aren’t about winning—they’re about stalling. Each motion delays justice for victims’ families, eroding trust in the ICC. Like al-Bashir’s endless deferrals, Duterte’s team bets on attrition, hoping global attention fades. The ICC, however, isn’t blinking—yet.

The Prosecution’s Gambit: Evidence Overload and Political Tightropes

Evidence: Precision with Gaps

On April 30, 2025, Khan unveiled 139 evidence items, split into four packages (Philippine Star):

- 28 contextual elements

- 85 on modes of liability under Article 25(3)

- 1 Davao murder

- 15 Barangay Clearance Operation killings

The 85 liability items aim to nail Duterte for ordering or abetting crimes, but the single Davao item feels thin for the DDS’s alleged body count. The 15 Barangay items lean on NGO reports, clashing with Manila’s 6,000-death figure versus HRW’s 30,000. This gap could let the defense question credibility if state records are deemed “official.”

Sovereignty vs. Justice

Khan walks a tightrope. Duterte’s allies frame the ICC as a neocolonial intruder, risking domestic backlash. The prosecution must cast the case as universal justice, not Western overreach, while addressing NGO-state data discrepancies to avoid fueling sovereignty gripes.

Rome Statute Realities: No Escape Hatch

The defense’s jurisdictional arguments are a willful misreading. Article 12(2) grants ICC authority over state party territory, and Article 127(2) ensures withdrawal doesn’t erase past crimes. Burundi (2017) seals this logic (Burundi ICC). Duterte’s “no legal basis” claim is as flimsy as arguing rain stops falling once you’re indoors.

The prosecution, however, isn’t bulletproof. Its NGO-heavy death tolls risk scrutiny under Article 17’s complementarity principle, which favors state investigations unless proven sham. Manila’s weak probes likely qualify, but Khan must explicitly prove this to fend off defense counterattacks.

Recommendations: Cutting Through the Fog

- To the ICC: Expedite proceedings with strict motion deadlines. Keep the September 23, 2025, hearing on track, signaling no tolerance for procedural games.

- To the Prosecution: File a preemptive motion affirming jurisdiction, citing Burundi and Article 127(2). Address evidence gaps (e.g., the lone Davao item) and reconcile NGO-state data to blunt credibility attacks.

- To Observers: Scrutinize the September hearing for judicial bias or political pressure. Ensure the Pre-Trial Chamber’s rulings align with Burundi and Rome Statute precedents.

The Verdict Isn’t In, But the Playbook Is Clear

Duterte’s defense is running a dictator’s greatest hits: dodge, demonize, delay. But the ICC, wielding the Rome Statute and a mountain of evidence, isn’t a pushover. Khan’s case, despite gaps, can prove Duterte’s role in industrialized murder. As September 2025 nears, the Court must stay sharp, slicing through procedural noise to deliver what Duterte dreads: accountability. For the drug war’s victims, anything less is betrayal.

Disclaimer: This is legal jazz, not gospel. It’s all about interpretation, not absolutes. So, listen closely, but don’t take it as the final word.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

- $2 Trillion by 2050? Manila’s Economic Fantasy Flimsier Than a Taho Cup

Leave a comment