By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — May 10, 2025

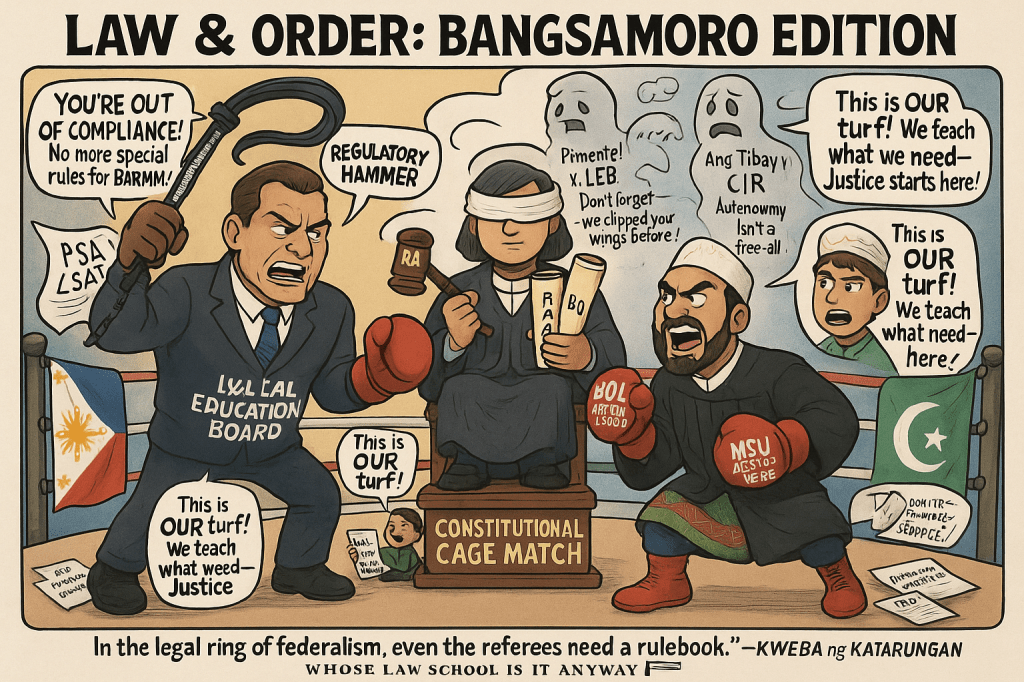

The Supreme Court’s temporary restraining order (TRO) issued on May 6, 2025, against the Legal Education Board’s (LEB) ban on Mindanao State University’s (MSU) law programs isn’t just a legal hiccup—it’s a constitutional cage match. The LEB, swinging its regulatory hammer under Republic Act No. 7662 (Legal Education Reform Act of 1993), aimed to shutter MSU’s law programs in Tawi-Tawi, Sulu, and Maguindanao and revoke its accreditation by Academic Year 2025-2026. MSU, backed by the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), cried foul, arguing the LEB’s “nationwide” authority stops at the Bangsamoro border, where the Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL) reigns supreme. The stakes? The delicate balance between national control over legal education and BARMM’s hard-won autonomy. Here’s a sharp, precedent-driven dissection of the dispute, with Kweba ng Katarungan’s signature swagger.

The Smackdown: LEB vs. MSU in BARMM’s Ring

The LEB’s closure order wasn’t a polite nudge—it was a death sentence for MSU’s law programs. Citing its mandate under RA 7662, the LEB barred MSU from opening new programs and yanked its accreditation, effectively ordering the college’s closure. MSU and petitioner Abdul Rahman Ltiph Nasser didn’t roll over. They filed separate certiorari petitions under Rule 65, alleging the LEB overstepped its jurisdiction and ignored BARMM’s educational autonomy under BOL, Art. IX, Sec. 16. The Supreme Court’s TRO, issued en banc, paused the LEB’s ban and demanded memoranda within 15 days to clarify whether the BOL trumps RA 7662 in BARMM’s turf.

The stakes are colossal. For the LEB, it’s about enforcing uniform standards across Philippine law schools. For MSU and BARMM, it’s about safeguarding regional self-governance and ensuring legal education access in underserved regions. This clash pits RA 7662’s national scope against the BOL’s promise of an autonomous education system, raising thorny questions about shared governance in a federalizing Philippines.

Legal Framework: National Muscle vs. Regional Moxie

Substantive Law: RA 7662 Meets BOL’s Grit

RA 7662 created the LEB to supervise legal education, with powers to set curricula, accredit programs, and enforce compliance nationwide. Section 7 empowers the LEB to “prescribe the basic curricula… aligned to the requirements for admission to the bar.” On paper, this gives the LEB carte blanche to regulate law schools, including MSU. But here’s the catch: MSU operates in BARMM, where RA 11054 (BOL) grants the Bangsamoro Government authority to “establish, maintain, and support a complete and integrated system of quality education” as a “subsystem of the national education system” (Art. IX, Sec. 16).

The BOL’s language is a tightrope. It demands conformity to national standards but doesn’t clarify who calls the shots on enforcement. Does the LEB get to wield its regulatory axe in BARMM, or must it defer to the Bangsamoro Government’s Ministry of Basic, Higher and Technical Education? The Supreme Court’s request for memoranda suggests it’s wrestling with this question. If the BOL’s autonomy clause overrides RA 7662, the LEB’s ban could be toast.

Procedural Law: Did LEB Play Fair?

MSU’s certiorari petitions allege the LEB acted with grave abuse of discretion, a steep hurdle under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court. To justify a TRO under Rule 58, MSU had to show irreparable injury (e.g., program closure) and a clear legal right (e.g., BARMM’s autonomy). The Supreme Court’s swift TRO issuance implies MSU cleared this bar, at least for now.

But the LEB’s case is on thin ice: due process. Under its own rules, the LEB must provide notice and a hearing before revoking accreditation. Did it consult BARMM or give MSU a fair shot? The record’s silence is deafening. The landmark case Ang Tibay v. CIR (G.R. No. L-46496, 1940) demands that administrative bodies like the LEB afford “substantial evidence” and a “fair and adequate” hearing. If the LEB steamrolled MSU without proper process, it’s courting a judicial beatdown.

Precedent-Driven Critique: Lessons from the Bench

Pimentel v. LEB: The LEB Isn’t God

In Pimentel v. LEB (G.R. No. 230642, 2019), the Supreme Court upheld the LEB’s jurisdiction but put it on a leash. The Court struck down the Philippine Law School Admission Test (PhiLSAT) as an unconstitutional overreach, citing violations of academic freedom and the Supreme Court’s authority over bar admissions. The takeaway? The LEB’s powers under RA 7662 aren’t absolute; they must respect constitutional limits, including institutional autonomy. MSU could argue the LEB’s ban infringes its academic freedom to offer programs tailored to BARMM’s needs, especially in lawyer-scarce regions.

Province of Sulu v. Executive Secretary: Autonomy with Strings

In Province of Sulu v. Executive Secretary (G.R. Nos. 242255, et al., 2021), the Supreme Court upheld the BOL’s constitutionality but stressed that BARMM’s autonomy isn’t a blank check. Regional powers must align with national standards, particularly in education. This precedent cuts both ways: it supports the LEB’s claim to set standards but bolsters MSU’s argument that enforcement in BARMM requires regional input. The LEB’s failure to consult BARMM reeks of procedural arrogance.

Ethical Lens: LEB’s Conduct Under Fire

The LEB’s actions must align with the Code of Professional Responsibility and Accountability (CPRA), which demands integrity and fairness (Canon 1). By issuing a blanket ban without apparent BARMM consultation, the LEB risks flunking the fairness test. The New Code of Judicial Conduct also requires administrative bodies to act impartially. If the LEB railroaded MSU to flex its national muscle, it’s not just a legal misstep—it’s an ethical fumble that erodes trust in legal education governance.

Critical Questions: Where’s the Line?

- Does BOL’s Autonomy Override RA 7662?

The BOL’s education clause (Art. IX, Sec. 16) suggests BARMM has primary control over its education system, but the “subsystem” language ties it to national standards. The Supreme Court could rule that the LEB sets standards while BARMM handles enforcement, creating a cooperative framework. If the Court leans hard into autonomy, RA 7662’s national scope could take a hit in BARMM. - Did LEB Overstep Without BARMM Consultation?

The LEB’s failure to engage BARMM’s Ministry of Education screams procedural hubris. Precedents like Ang Tibay and Pimentel demand due process and respect for institutional autonomy. Without evidence of consultation, the LEB’s ban looks like a power grab, ripe for reversal. - Redefining Shared Governance?

This case could be a landmark for federalism in the Philippines. A ruling favoring MSU might embolden other autonomous regions to challenge national regulators, forcing a rethink of shared governance. Conversely, upholding the LEB could centralize power, risking tension with BARMM’s devolved powers.

The Legal Battlefield: A Snapshot

| Issue | LEB’s Position (RA 7662) | MSU/BARMM’s Defense (BOL) | Precedent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jurisdiction | National authority to regulate all law schools. | BARMM’s autonomy over education limits LEB’s reach. | Pimentel v. LEB: LEB powers not absolute. |

| Due Process | Accreditation rules justify closure order. | No consultation or hearing violates fairness. | Ang Tibay v. CIR: Right to hearing mandatory. |

| Autonomy | National standards trump regional control. | BOL’s education clause demands regional input. | Province of Sulu: Autonomy aligns with national law. |

Recommendations: Fixing the Mess

- For the Supreme Court: Leverage the memoranda to delineate the LEB’s standard-setting role from BARMM’s enforcement powers. A balanced ruling could affirm the LEB’s authority to set national benchmarks while requiring BARMM consultation for implementation, preserving both uniformity and autonomy.

- For Legislators: Amend RA 7662 to explicitly address BARMM’s autonomy, perhaps by mandating joint oversight with the Bangsamoro Government for law schools in the region. Clarity now prevents chaos later.

- For the LEB: Embrace cooperative federalism. Set standards but defer to BARMM on enforcement, especially for culturally sensitive programs like MSU’s. Steamrolling regional players isn’t just bad optics—it’s a losing strategy in a federalizing state.

Conclusion: A Constitutional Cliffhanger

The Supreme Court’s TRO isn’t just a lifeline for MSU—it’s a signal that the LEB’s “nationwide” authority might not survive a BARMM showdown. By pitting RA 7662 against the BOL, this case tests the Philippines’ commitment to federalism and fair play. Precedents like Pimentel and Province of Sulu suggest the LEB’s ban could crumble if it ignored due process or BARMM’s autonomy. For now, the Court’s call for memoranda keeps us on edge, but one thing’s clear: the LEB’s days of unchecked power may be numbered. Stay tuned—this constitutional smackdown is far from over.

Key Citations:

- Republic Act No. 7662, Legal Education Reform Act of 1993.

- Republic Act No. 11054, Bangsamoro Organic Law, Art. IX, Sec. 16.

- Pimentel v. Legal Education Board, G.R. No. 230642, 2019.

- Province of Sulu v. Executive Secretary, G.R. Nos. 242255, et al., 2021.

- Ang Tibay v. CIR, G.R. No. L-46496, 1940.

- Code of Professional Responsibility and Accountability, Canon 1.

- New Code of Judicial Conduct.

Disclaimer: This is legal jazz, not gospel. It’s all about interpretation, not absolutes. So, listen closely, but don’t take it as the final word.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

- $2 Trillion by 2050? Manila’s Economic Fantasy Flimsier Than a Taho Cup

- $26 Short of Glory: The Philippines’ Economic Hunger Games Flop

Leave a comment