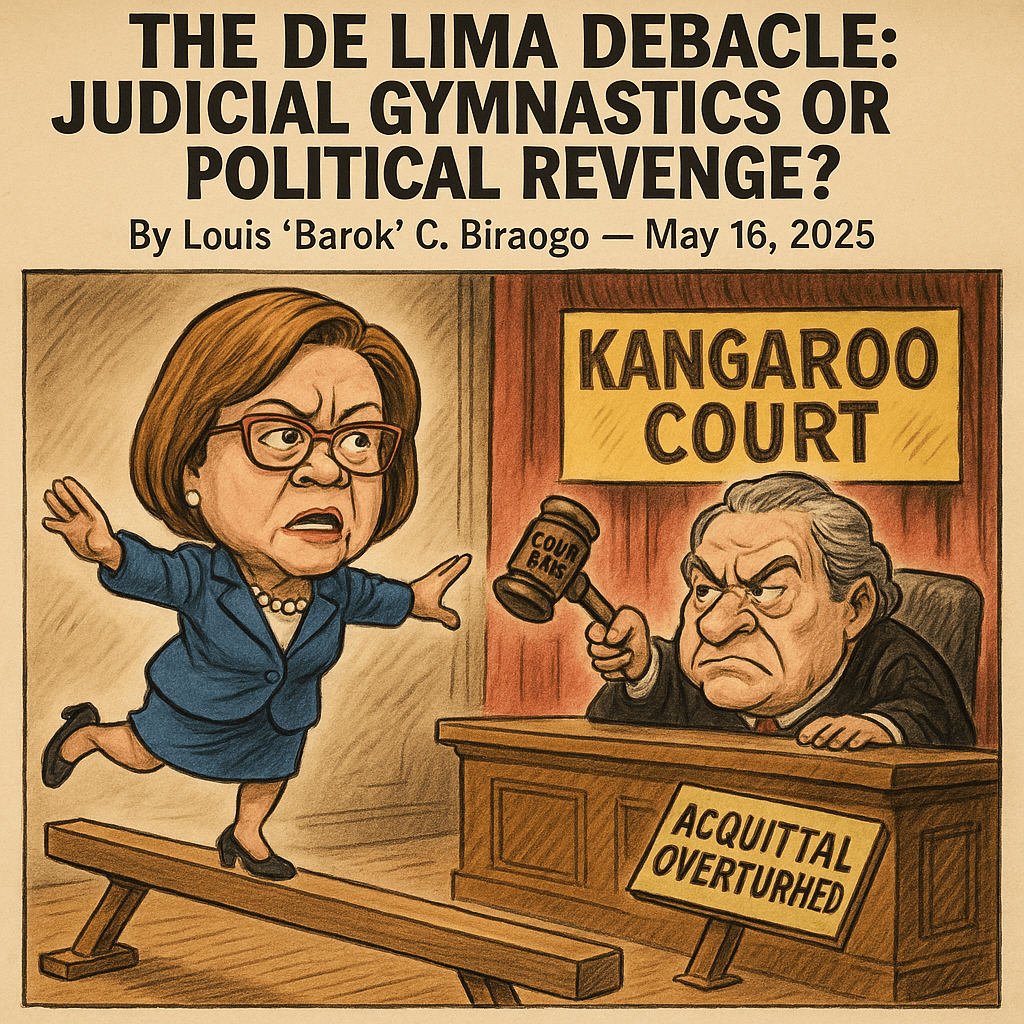

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — May 16, 2025

LEILA de Lima, former Philippine senator and Duterte’s fiercest critic, thought she’d clawed her way out of a seven-year legal purgatory. Cleared of all drug charges by June 2024, she was ready to storm back into Congress as ML Party-list’s first nominee and join the prosecution team for Vice President Sara Duterte’s impeachment trial. But the Court of Appeals (CA) had other plans. On April 30, 2025, it voided her 2023 acquittal in one drug case, ordering the Muntinlupa Regional Trial Court (RTC) to rewrite its decision like a professor demanding a do-over on a sloppy essay. The CA’s reasoning? The RTC’s ruling was “procedurally deficient” and leaned too heavily on a witness’s recantation. De Lima calls it a mere clarification request; the Solicitor General smells blood. What’s really going on here—a judicial fix or a political hit job? Let’s slice through the spin.

Judicial Whiplash: Grave Abuse or Nitpicking?

The CA’s Eighth Division, in a 12-page decision, declared the RTC’s acquittal of De Lima and co-accused Ronnie Dayan null and void, citing “grave abuse of discretion” by Judge Abraham Alcantara. The sin? Failing to “clearly state the facts and the law” behind the acquittal, as mandated by Rule 120, Section 2 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure. The RTC’s decision, the CA sniffed, hinged solely on the 2022 recantation of Rafael Ragos, former Bureau of Corrections chief, who flipped from accusing De Lima of drug trade involvement to claiming he was coerced into lying. No detailed analysis of how Ragos’s about-face dismantled the prosecution’s case, no enumeration of which crime elements went unproven—just a judicial shrug and an acquittal.

Is this a legitimate fix? Rule 120 demands transparency in judgments, and the Supreme Court has long insisted on it. In People v. Judge Dacuycuy (1988), the Court scolded judges for half-baked rulings that leave appellate courts guessing. The RTC’s reliance on Ragos’s recantation without dissecting its impact smells like the kind of corner-cutting that could justify a remand. But let’s not kid ourselves: the CA’s hyper-focus on procedural clarity feels like a masterclass in nitpicking. The RTC’s 39-page decision wasn’t exactly a Post-it note; it concluded Ragos’s retraction “created reasonable doubt” about De Lima’s role in a New Bilibid Prison drug conspiracy. If that’s not enough, what is? The CA’s demand for a “detailed enumeration” of retracted statements reads like a judicial PowerPoint fetish—form over substance. This isn’t about clarity; it’s about opening a backdoor to revisit an acquittal the Solicitor General, Menardo Guevarra (Duterte’s former Justice Secretary, no less), couldn’t stomach.

Sidebar: Rewriting Acquittals—The Judicial ‘Per My Last Email’

The CA’s order to “rewrite” the RTC’s decision is the legal equivalent of a passive-aggressive email demanding you “fix” a perfectly fine report. “Please clarify your acquittal, dear RTC, and this time, use bullet points.” If this is how courts handle final judgments, what’s next—red-lining constitutional rights for grammar? The CA’s fixation on penmanship over justice is a farce that undermines judicial finality. Next time, maybe just send a Google Doc with track changes.

Double Jeopardy or Double Standard?

De Lima’s camp is screaming double jeopardy, and they’ve got a point. Article III, Section 21 of the 1987 Constitution is crystal clear: no one gets tried twice for the same offense after an acquittal. De Lima’s 2023 acquittal was promulgated, final, and—per her lawyers—“unappealable.” She’s not wrong to clutch that shield; the Supreme Court has zealously guarded it. But the CA and Solicitor General are playing a sly game, leaning on a narrow exception carved out in People v. Lacson (2003) and People v. Laguio, Jr. (2007). If an acquittal is void due to grave abuse of discretion—think a judge tossing a case on a whim or denying the prosecution a fair shot—double jeopardy doesn’t attach. The CA argues the RTC’s sloppy reasoning amounts to such an abuse, rendering the acquittal a legal nullity.

Here’s the rub: this exception is supposed to be rare, reserved for egregious judicial overreach. Lacson involved a case where the trial court dismissed charges without letting the prosecution present evidence. Laguio dealt with a judge ignoring clear proof of guilt. The RTC’s sin—failing to dot every “i” in its analysis—hardly rises to that level. De Lima’s team argues the acquittal, however imperfect, was based on evidence (Ragos’s recantation) and followed a full trial. Calling it “void” to sidestep double jeopardy feels like creative jurisdiction-stretching, a judicial sleight-of-hand to keep De Lima in the crosshairs. The CA’s logic implies any acquittal with a typo could be reopened, gutting the finality of judgments. If this holds, the Supreme Court better brace for a flood of certiorari petitions from sore-loser prosecutors.

Recantation Roulette: Why Can’t the Judiciary Make Up Its Mind?

The CA’s beef with Ragos’s recantation is peak judicial schizophrenia. In 2016, Ragos testified that he delivered P5 million in drug money to De Lima’s house. In 2022, he swore he was coerced by Duterte’s Justice Secretary Vitaliano Aguirre II to lie. The RTC bought the recantation, saying it “created reasonable doubt” about De Lima’s guilt. The CA, however, scolded the RTC for not spelling out which parts of Ragos’s original testimony were retracted and how that unraveled the prosecution’s case. Fair enough—courts shouldn’t just swallow recantations whole. But here’s the kicker: Philippine jurisprudence, like People v. Quijada (2014), treats recantations with suspicion, warning they’re often tainted by fear or bribes. So why fault the RTC for crediting Ragos’s flip-flop when the default is to distrust it?

The judiciary’s flip-flopping on recantations is laughable. If courts routinely side-eye recantations, the RTC’s decision to accept Ragos’s wasn’t some rogue move—it aligned with the case’s context. Ragos claimed coercion by Duterte’s inner circle, a plausible story given the drug war’s dirty playbook. The CA’s demand for a blow-by-blow analysis of the recantation’s impact feels like holding the RTC to a standard no one else meets. Meanwhile, the prosecution’s case leaned on Ragos’s original testimony, which he himself torched. If the star witness admits to perjury, what’s left? The CA’s ruling dodges that inconvenient truth, opting for procedural scolding over substantive justice. It’s like telling a chef their soup is bad because they didn’t list every spice.

Duterte’s Long Shadow: A Political Hit Job?

Let’s talk timing, because it’s shadier than a Manila back alley. The CA’s ruling drops just as De Lima wins a congressional seat and gears up to prosecute Sara Duterte’s impeachment. Coincidence? Please. De Lima’s legal saga began in 2017, when Rodrigo Duterte, then president, unleashed a drug war that left thousands dead and her in detention for nearly seven years. As a senator, she probed Duterte’s Davao Death Squad, earning his wrath and a slew of charges widely seen as trumped-up. Amnesty International called her acquittals “long overdue,” slamming the cases as political persecution. The CA’s move to reopen one acquittal now, with Guevarra (Duterte’s ex-Justice Secretary) leading the charge, reeks of score-settling.

The CA’s historical deference to executive pressure doesn’t help its case. During Duterte’s reign, courts often bent to his will—think Maria Lourdes Sereno’s ouster as Chief Justice. This ruling fits the pattern: a judiciary still dancing to the Duterte dynasty’s tune, now targeting De Lima as she threatens Sara’s political future. The Solicitor General’s certiorari petition, filed after “extensive consultation” with the DOJ, feels less like a legal crusade than a political favor. And let’s not ignore Guevarra’s role—serving Duterte then, challenging De Lima now. It’s not karma; it’s a vendetta with a gavel.

Theater of the Absurd: Law or Performance Art?

The CA’s remand order is a masterstroke of legal theater. De Lima, fresh off her ML Party-list victory, is poised to re-enter Congress as a reform advocate. Yet the CA insists the RTC rewrite a two-year-old acquittal, as if a clearer font will change the outcome. This isn’t justice; it’s performance art for Duterte loyalists. The case’s political subtext—De Lima’s defiance of a regime that demonized her—makes the CA’s procedural fuss look like a distraction. She’s already been acquitted in all three drug cases, freed on bail in 2023, and vindicated by a public that elected her. The CA’s ruling feels like a desperate attempt to tarnish her comeback, not a quest for judicial rigor.

Contrast this with the stakes: De Lima’s not going back to jail (yet), as her legal team notes the acquittal remains enforceable pending Supreme Court review. But the optics are brutal—her congressional debut is now shadowed by a legal cloud, courtesy of a court that can’t let go of a case most see as a sham. This is law as spectacle, where the process is the punishment.

Recommendations: Stop the Circus

To the Judiciary: Get a grip. If acquittals can be voided for failing to cross every “t,” what’s left of finality? The CA’s ruling risks turning Rule 120 into a weapon for endless litigation. The Supreme Court must clarify when “grave abuse” justifies unraveling a judgment and when it’s just appellate overreach. A bright-line rule would curb this judicial free-for-all.

To De Lima: Call your own bluff. If double jeopardy is your shield, why sweat a rewritten decision? Push for a swift Supreme Court appeal and use your congressional platform to expose the case’s political roots. Your voters already see through the charade—lean into it.

To the Public: Keep your eyes on the Supreme Court’s timeline. If this case drags past De Lima’s House term, it’s not about justice—it’s about derailing her agenda. Track the appeal’s pace; delay is the real weapon here. And maybe ask why Guevarra’s so obsessed with a case built on a recanted lie.

Judicial Charade: The Kangaroo Courts of Manila

Leila de Lima’s saga is a grim reminder that in the Philippines, justice is often a political pawn. The CA’s ruling isn’t about clarity—it’s about keeping a critic in check. As she fights on, Congress-bound but battle-scarred, the judiciary’s credibility sinks deeper into the muck. So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the kangaroo courts of Manila, where acquittals are rewritten, and old scores never die.

Key Citations

- Court of Appeals voids De Lima’s acquittal in 1 drug case, remands to RTC

- CA nullifies De Lima acquittal by Muntinlupa RTChttps://www.gmanetwork.com/news/topstories/nation/946281/court-of-appeals-nullifies-de-lima-acquittal-by-muntinlupa-rtc/story/

- Leila de Lima cleared of all drug charges

- Leila de Lima’s acquittal a long-overdue step towards justice

Research Tables

Legal Provisions

| Provision | Relevance to Case |

|---|---|

| Article III, Section 21 (Constitution) | Protects against double jeopardy, but may not apply if acquittal is void. |

| Rule 120, Section 1 (Criminal Procedure) | Requires judgments to clearly state facts and law, central to CA’s criticism of RTC. |

| Rule 120, Section 2 (Criminal Procedure) | Mandates detailed reasoning in judgments, violated by RTC’s reliance on recantation. |

Case Law

| Case Name | Citation | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| People v. Judge Dacuycuy | G.R. No. L-45306, March 25, 1988 | Emphasizes judgments must be based on evidence, not arbitrary. |

| People v. Lacson | G.R. No. 149453, June 10, 2003 | Clarifies double jeopardy does not attach to void judgments. |

| People v. Laguio, Jr. | G.R. No. 128587, March 16, 2007 | States double jeopardy exception for grave abuse of discretion. |

| People v. Quijada | G.R. No. 189351, July 23, 2014 | Highlights caution in accepting recantations without corroboration. |

Disclaimer: This is legal jazz, not gospel. It’s all about interpretation, not absolutes. So, listen closely, but don’t take it as the final word.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

- $2 Trillion by 2050? Manila’s Economic Fantasy Flimsier Than a Taho Cup

Leave a comment