By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — May 25, 2025

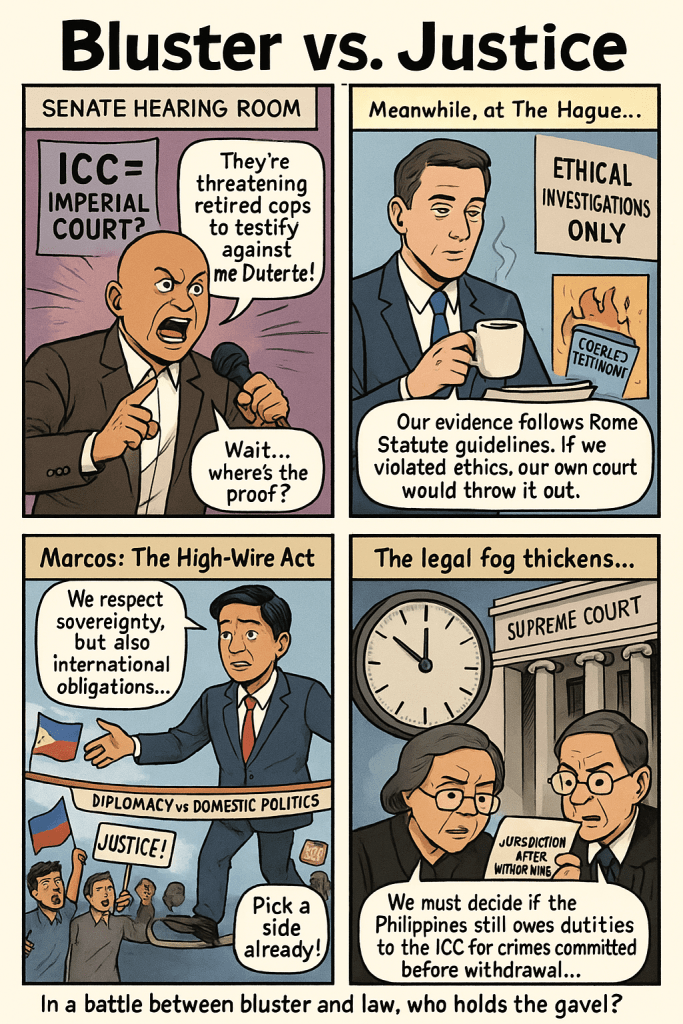

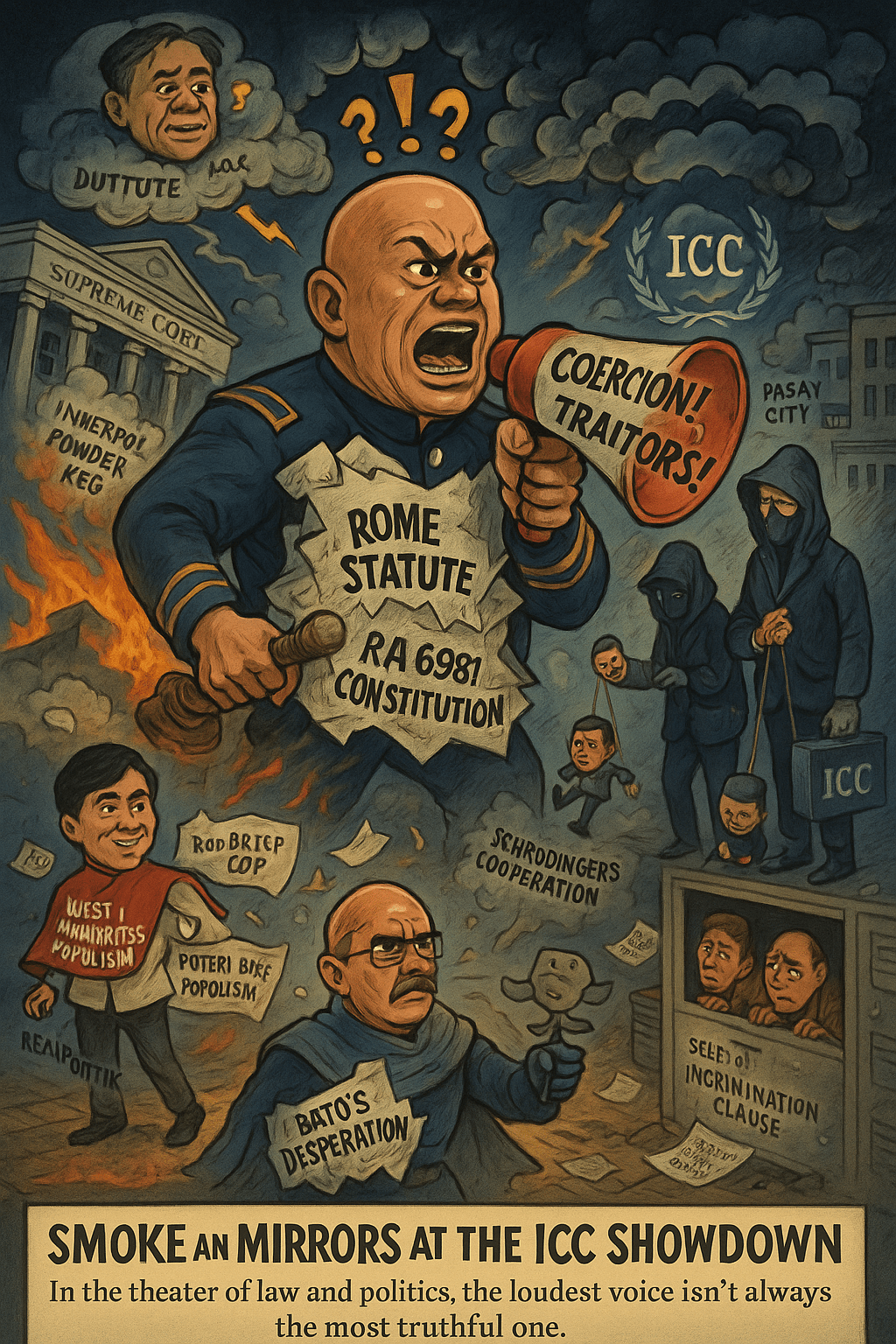

SENATOR Ronald “Bato” Dela Rosa’s fiery accusations against International Criminal Court (ICC) investigators—claiming they’re strong-arming retired Philippine National Police (PNP) officers into fingering him and former President Rodrigo Duterte—hit like a thunderclap. But is it lightning or just hot air? In a May 23, 2025, GMA News report, Dela Rosa alleges ICC operatives in Pasay City hotels are bullying ex-cops with threats of prosecution to sign pre-prepared affidavits. He slams President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr.’s supposed reconciliation overtures as a sham, demanding the deportation of these investigators and questioning Marcos’s rejection of ICC jurisdiction. If Dela Rosa’s right, the ICC just sank its own ship. But where’s the evidence? This hard-hitting critique rips into the legal merit, political scheming, and fallout of Dela Rosa’s claims, exposing a saga that’s as much about courtroom carnage as it is about political puppetry.

Legal Firestorm: Can Bato’s Coercion Claims Survive Scrutiny?

Bato’s Battle Cry: A Legitimate Gripe or Empty Noise?

If ICC investigators are twisting arms, Dela Rosa’s got a legal sledgehammer. The Rome Statute (2002), Article 55(2)(b), bans “coercion, duress or threat” in investigations, while Article 68(1) demands protecting witnesses’ safety and dignity. Coercion would torpedo the ICC’s case, as seen in Prosecutor v. Lubanga (ICC-01/04-01/06, 2012), where tainted evidence was excluded for ethical breaches. Philippine law doubles down: Republic Act No. 6981 (1991), Section 3(c), shields witnesses from harassment, and Section 17 slaps penalties on intimidators. The Supreme Court’s People v. Teehankee (G.R. No. 167013, 2008) rules coerced testimony void, and Galvante v. Office of the Ombudsman (G.R. No. 166682, 2008) protects witnesses from unsafe compulsion.

Can retired PNP officers dodge ICC subpoenas? Maybe. Pangilinan v. Cayetano (G.R. No. 238775, 2021) confirms residual ICC obligations for 2011–2019 crimes, but the 1987 Philippine Constitution, Article III, Section 17, allows refusing self-incriminating testimony. Dela Rosa’s sovereignty argument gains traction under Article III, Section 2, which guards against unauthorized foreign actions. His Supreme Court petition, challenging Duterte’s March 11, 2025, arrest, could argue Marcos’s facilitation violated domestic law, especially since the Philippines ditched the Rome Statute in 2019.

Here’s the rub: Dela Rosa’s got no proof. No names, no affidavits, no specifics—just accusations. Without evidence, his claims are legally DOA, a flimsy shield against the ICC’s probe.

ICC’s Counterpunch: Bato’s Claims Don’t Add Up

If Dela Rosa’s spinning tales, he’s playing a dangerous game. The ICC’s jurisdiction over the “war on drugs” (2016–2019) is ironclad under Rome Statute, Article 127, which preserves obligations for pre-withdrawal crimes, backed by Pangilinan v. Cayetano. Duterte’s arrest, facilitated via Interpol, complies with Rome Statute, Article 59, requiring no domestic judicial approval, and Republic Act No. 9851, Section 17 (2009), which greenlights ICC surrenders. ICC-accredited lawyer Joel Butuyan confirms this legality Manila Standard, 2025. Dela Rosa’s sovereignty rant crumbles—Marcos acted within the law.

The Lubanga precedent cuts against Bato too. While it nixes coerced evidence, it shows the ICC’s obsession with ethical standards. The ICC’s May 2025 request to delay witness disclosure, citing safety concerns, screams compliance with Article 68(1) Philstar, 2025. No evidence supports Dela Rosa’s coercion claims; X posts suggest prior PNP cooperation was coercion-free. Retired officers resisting subpoenas face uphill battles—RA 9851 and Pangilinan mandate cooperation, and self-incrimination defenses are shaky against ICC’s international clout. Bato’s “powerless cops” narrative is more sob story than legal slam dunk.

Political Powder Keg: Marcos’s Duplicity or Bato’s Desperation?

Marcos’s Double-Dealing: Hypocrisy or High-Stakes Chess?

Marcos claims no ICC jurisdiction while investigators roam Pasay. Schrödinger’s cooperation? He’s rejected ICC authority since 2022, citing a “functioning” justice system under Rome Statute, Article 17 Philstar, 2024. Yet, his administration allowed ICC probes by 2024 and handed Duterte to The Hague on March 11, 2025, a move hailed by Human Rights Watch (2025). Hypocrisy or realpolitik?

Dela Rosa calls it betrayal. Marcos’s May 2025 reconciliation talk with the Dutertes—post their 2024 feud, including Sara Duterte’s resignation and assassination threat—looks like lip service when he’s enabling ICC arrests JusticeInfo, 2025. Bato’s deportation demand tests Marcos’s loyalty to the Duterte base, crucial for his 2022 win. But Marcos is playing 4D chess. With 55% of Filipinos backing ICC cooperation, he’s appeasing human rights groups and Western allies via RA 9851 while dodging domestic backlash with “melancholy” platitudes Carnegie Endowment, 2025. It’s not hypocrisy—it’s survival in a polarized Philippines.

Bato’s Witch Hunt: Oversight or Intimidation Tactic?

Dela Rosa’s Senate inquiry is less about truth and more about terrorizing witnesses. Calling Filipino ICC collaborators “traitors” mirrors Sara Duterte’s November 2024 anti-foreign rants, weaponizing nationalism to shield himself and Duterte JusticeInfo, 2025. As the drug war’s PNP chief and self-proclaimed “number two accused,” Bato’s got skin in the game GMA News, 2025. His inquiry could rally PNP loyalty and drug war fans, but it’s a blatant intimidation play. Human rights lawyer Kristina Conti labels it a “fishing expedition” to silence whistleblowers, especially after the ICC flagged witness safety fears Philstar, 2025. This isn’t oversight—it’s a desperate bid to dodge The Hague.

Ethical Quagmire: Witnesses Caught in the Crossfire

Bato’s “Traitor” Tirade: A Legal Landmine?

Dela Rosa’s outing of “Filipino collaborators” as traitors is a reckless shot. RA 6981, Section 3(c), protects witnesses from harassment, and Section 17 criminalizes intimidation. His rhetoric could expose cooperators to retaliation, especially after the ICC’s safety-driven disclosure delay Philstar, 2025. It’s a chilling effect on steroids, echoing Sara Duterte’s anti-ICC vitriol. If baseless, Bato risks defamation under the Revised Penal Code, Article 353, though senatorial immunity 1987 Constitution, Article VI, Section 11 shields him—for now. He’s playing with fire, endangering witnesses and justice itself.

ICC’s Ethical Tightrope: Coercion or Conspiracy?

If ICC investigators are bullying ex-cops, they’re shredding their own rulebook. The ICC Code of Conduct for the Office of the Prosecutor (2013) demands impartiality and no coercion, backed by Rome Statute, Article 55(2)(b). Lubanga proves the ICC doesn’t tolerate tainted evidence. Coercion would sink the Duterte case, handing Bato a win. But there’s no proof—nada. The ICC’s protective measures suggest ethical rigor, not foul play. Dela Rosa’s conspiracy theory, absent evidence, looks like a Hail Mary to deflect accountability. Defamation against the ICC isn’t likely—it’s an institution—but his credibility’s on life support if this falls apart.

Battle Plan: Cutting Through the Chaos

- Supreme Court, Move Fast: The Court must rush Dela Rosa’s petition on ICC jurisdiction and Duterte’s arrest. Pangilinan v. Cayetano hints at cooperation duties, but a clear ruling on RA 9851’s scope post-withdrawal is critical to stop political grandstanding.

- Lock Down Witness Safety: The ICC and Philippines should ink an MOU to regulate investigations, aligning with RA 6981 and Rome Statute, Article 68(1). This would ensure transparency, protect witnesses, and neuter coercion claims.

- Marcos, Pick a Side: Marcos’s half-in, half-out ICC stance is a mess. He must either embrace cooperation under RA 9851, risking Duterte’s base, or deport investigators, facing global backlash. Stop straddling—lead or step aside.

The Final Verdict

Dela Rosa’s coercion claims could rock the ICC if true, backed by Rome Statute, Article 55 and RA 6981. But with zero evidence, they’re a political smokescreen to shield him and Duterte. His “traitor” rhetoric risks violating witness protections, while his Senate inquiry smells like a witch hunt. Marcos’s ICC cooperation isn’t duplicity—it’s realpolitik, balancing global and domestic pressures. The Supreme Court and an MOU could clear the fog, but only if Marcos grows a spine. The only thing thinner than Dela Rosa’s evidence is Marcos’s commitment to reconciliation.

References

- Carnegie Endowment. (2025). Polarized opinion: The arrest of Duterte. https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2025/03/polarized-opinion-the-arrest-of-duterte?lang=en

- GMA News. (2025, May 23). Bato: ICC investigators in PH forcing ex-PNP execs to testify vs. me, Duterte. https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/topstories/nation/947108/bato-icc-investigators-in-ph-forcing-ex-pnp-execs-to-testify-vs-me-duterte/story/

- Human Rights Watch. (2025, March 12). Philippines: Duterte arrested on ICC warrant. https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/03/12/philippines-duterte-arrested-icc-warrant

- International Criminal Court. (2002). Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/RS-Eng.pdf

- International Criminal Court. (2012). Prosecutor v. Lubanga, ICC-01/04-01/06. https://casebook.icrc.org/case-study/icc-prosecutor-v-lubangahttps://casebook.icrc.org/case-study/icc-prosecutor-v-lubanga

- International Criminal Court. (2013). Code of Conduct for the Office of the Prosecutor. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/iccdocs/oj/otp-COC-Eng.PDF&ved=2ahUKEwjiuIzk2buNAxXJ8zgGHZByACgQFnoECBgQAQ&usg=AOvVaw2o0l8E8BxyKqaVXHigRZXa

- JusticeInfo. (2025). ICC caught in clan rivalry in the Philippines. https://www.justiceinfo.net/en/140756-icc-caught-clan-rivalry-philippines.html

- Philstar. (2024, February 21). Marcos not changing stance on ICC. https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2024/02/21/2334929/marcos-not-changing-stance-icc

- Philstar. (2025, May 20). Safety concerns prompt ICC prosecutor to seek deadline extension for witness disclosure in Duterte case. https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.philstar.com/headlines/2025/05/19/2444260/icc-prosecutor-seeks-delay-disclosure-witnesses-duterte-case-due-safety-concerns/amp/

- Republic Act No. 6981. (1991). Witness Protection, Security, and Benefit Act. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1991/04/24/republic-act-no-6981/

- Republic Act No. 9851. (2009). Philippine Act on Crimes Against International Humanitarian Law. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2009/12/11/republic-act-no-9851/

- Supreme Court of the Philippines. (2021). Pangilinan v. Cayetano, G.R. No. 238775. https://lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2021/mar2021/gr_238875_2021.html

Disclaimer: This is legal jazz, not gospel. It’s all about interpretation, not absolutes. So, listen closely, but don’t take it as the final word.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

- $2 Trillion by 2050? Manila’s Economic Fantasy Flimsier Than a Taho Cup

- $26 Short of Glory: The Philippines’ Economic Hunger Games Flop

Leave a comment