By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — May 27, 2025

IN A Manila barrio, where the air hums with the weight of memory, a needle drops onto a worn vinyl of Anak. The crackle is a whisper from 1978, a confession that spills from Freddie Aguilar’s guitar like a river breaking through stone—raw, unapologetic, a father’s lament for a wayward child. That song, born of guilt and love, stretched across oceans, its melody translated into 51 languages, a staggering 33 million copies sold, touching hearts from Japan to Angola. But for Filipinos, it was more than a global hit; it was a mirror held up to the intimate ache of family, the specificity of our longing that somehow became universal. Freddie Aguilar, who left us on May 27, 2025, at 72, was no mere singer. He was a chronicler of our archipelago’s soul, a troubadour whose strings were both balm and blade—strumming lullabies for the disowned and dirges for the disappeared.

Aguilar’s voice was a paradox, as tender as it was defiant. Born Ferdinand Pascual Aguilar in Santo Tomas, Isabela, in 1953, he began composing at 14, abandoning Electrical Engineering to chase the muse that called him to the streets. By 18, he was a street performer, his guitar a companion through estrangement, his songs a bridge back to forgiveness. Anak was his atonement, a personal wound that bled into the collective consciousness of a nation. But Aguilar was never content to dwell in the personal alone. His music became a weapon, a rallying cry. In Bayan Ko, a 1928 hymn he reimagined, he didn’t just sing a revolution; he became the tremor in its voice. At Ninoy Aquino’s funeral in 1983, and later during the 1986 People Power Revolution, that song was a pulse, a collective hum that shook the Marcos regime to its core. It was banned under martial law, as were others like Katarungan and Luzviminda, but Aguilar’s melodies could not be silenced—they were the sound of a people refusing to bow.

His discography reads like a map of Filipino struggle and dignity. In Magdalena, he gave voice to a woman forced into prostitution, her tragedy a quiet indictment of societal neglect. Mindanao bore witness to the south’s endless conflict, its notes heavy with the weight of histories untold. Bulag, Pipi at Bingi—blind, mute, and deaf—skewered leaders who turned away from the poor. Aguilar was a folk chronicler, his songs searing social documents that refused to let us forget. He wove the personal and political into a single thread, his guitar a loom that spun stories of both intimate sorrow and collective defiance. To hear him was to feel the Philippines in your bones—the jeepney’s clatter, the barrio’s dust, the weight of a history that both binds and breaks us.

Yet Aguilar’s legacy is not without shadows. His later years brought controversies—his 2013 marriage to a 16-year-old after converting to Islam drew sharp criticism, and his political alignments, including support for Rodrigo Duterte, stirred debate among fans who saw him as a revolutionary. He ran for senator in 2019 and lost, a reminder that the stage, not the ballot, was his true arena. But these contradictions do not diminish his artistry; they deepen it. Aguilar was a man of his time, flawed and fierce, his life a reflection of the same turbulent currents his music sought to navigate. Even his silences were charged, the spaces between notes carrying the unspoken grief of a nation.

In his final days at the Philippine Heart Center, as his wife Jovie Albao shared glimpses of his fading strength, the nation held its breath. Now, as tributes pour in—Senator-elect Tito Sotto’s words, “He will now be performing for a far greater audience,” echoing across the ether—Aguilar’s melodies linger like a second wind. I imagine him back on the streets of Ermita, a young man with a guitar, playing for coins at the Hobbit House in 1973, his voice a spark that would one day set the archipelago ablaze. Ka Freddie, your songs are not gone; they haunt us still, a stubborn flame that refuses to die, singing memory into the marrow of our days.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

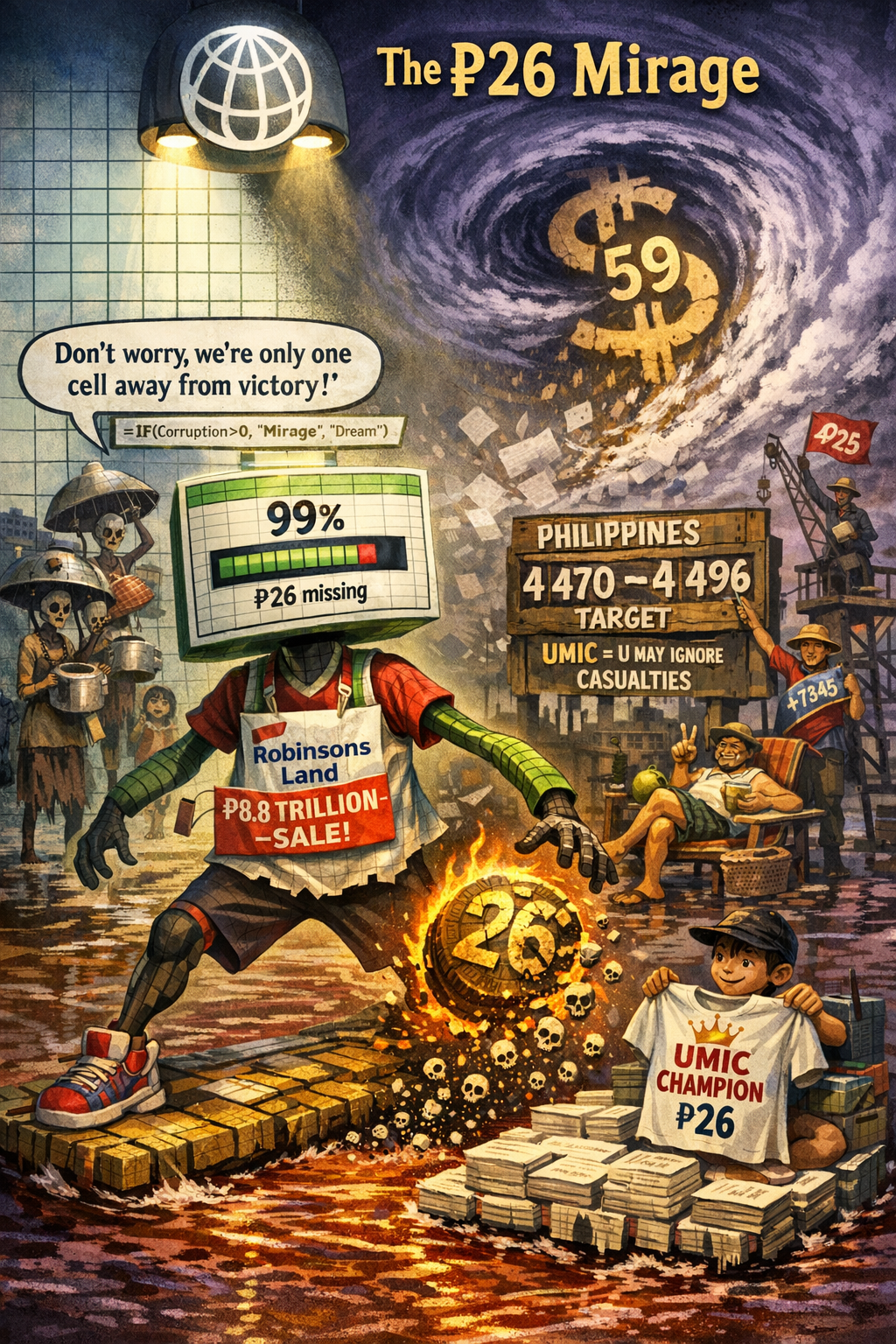

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

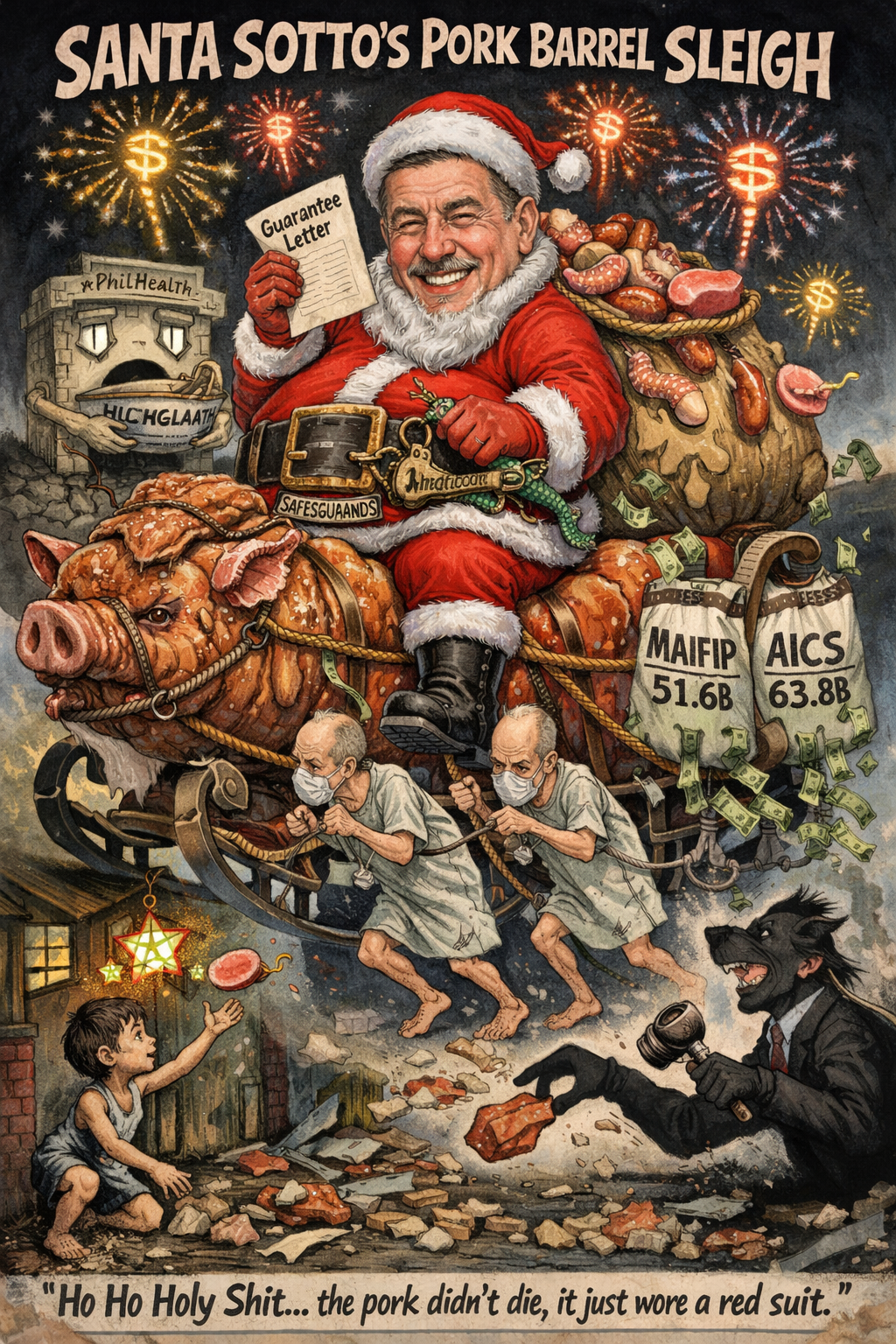

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

- “Allocables”: The New Face of Pork, Thicker Than a Politician’s Hide

- “Ako ’To, Ading—Pass the Shabu and the DNA Kit”

- Zubiri’s Witch Hunt Whine: Sara Duterte’s Impeachment as Manila’s Melodrama Du Jour

- Zaldy Co’s Billion-Peso Plunder: A Flood of Lies Exposed

Leave a comment