By Louis ‘Barok’ C Biraogo — May 29, 2025

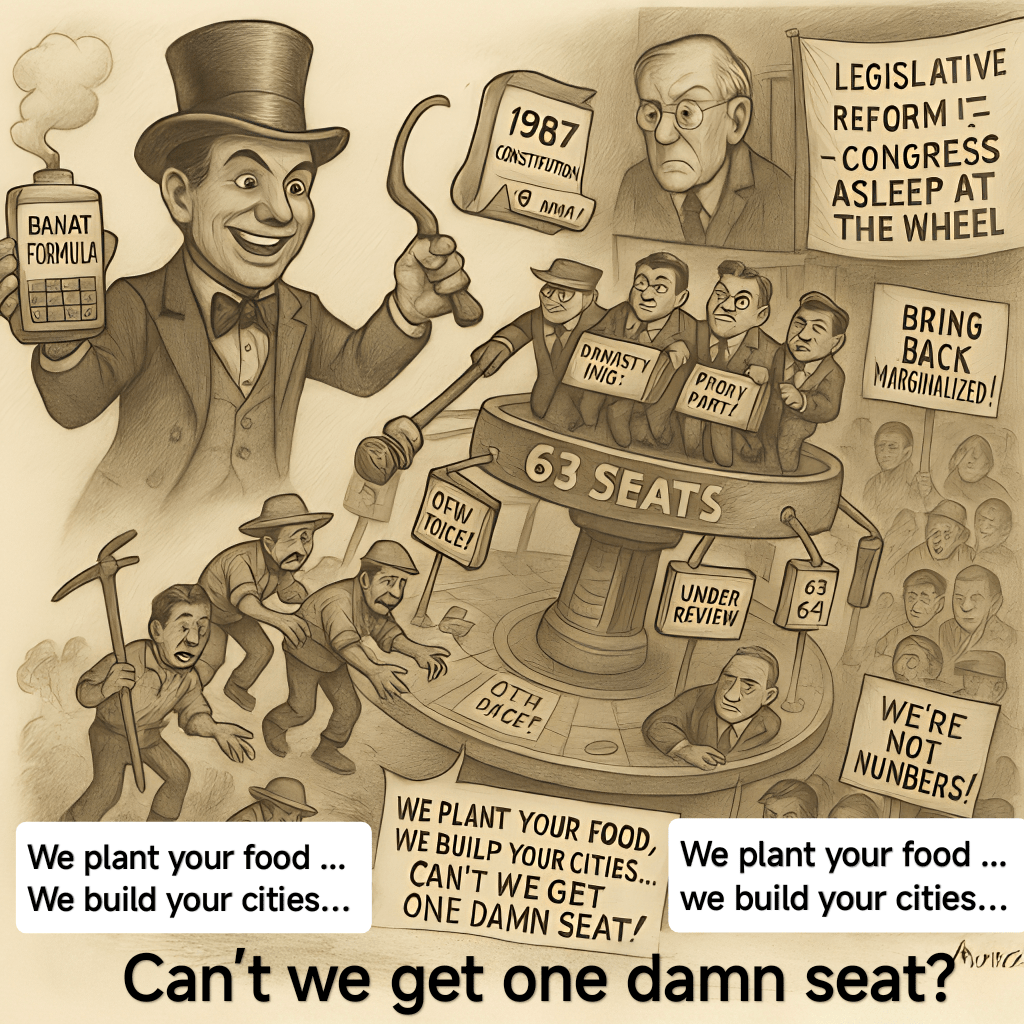

THE party-list system, enshrined in the 1987 Philippine Constitution to amplify marginalized voices, is under fire again. The OFW Party-list’s urgent petition before the Supreme Court, filed May 26, 2025, accuses the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) of botching its math and betraying the system’s core purpose. With Resolution 14-25 allocating 63 party-list seats for the 20th Congress, the group cries foul, claiming a constitutional shortfall, a flawed “Banat” formula, and a system hijacked by political elites. But does their case hold water, or is it a quixotic tilt at COMELEC’s windmill? Let’s dissect the legal, procedural, and ethical mess—and why the real scandal might be bigger than a single seat.

Constitutional Compliance: The 63 vs. 64 Seat Debate

The OFW Party-list argues that 20% of 318 House seats (63.6) should round up to 64, citing Article VI, Section 5(2) of the 1987 Constitution, which mandates that party-list representatives “shall constitute twenty per centum” of the House. At first glance, their math seems persuasive—63.6 is closer to 64 than 63, right? But the Constitution isn’t a middle school rounding exercise.

In BANAT v. COMELEC (G.R. No. 179271, 2009), the Supreme Court clarified that the 20% quota is an upper limit, not a mandatory target. With 254 district representatives, confirmed for the 2025 elections per House of Representatives Composition, the total House size is 254 + P, where (P) is party-list seats. The constitutional constraint is P \leq 0.2 \times (254 + P). Solving:

P \leq 50.8 + 0.2P0.8P \leq 50.8P \leq 63.5

Since seats can’t be fractional, 63 is the maximum without breaching the 20% cap (63/317 ≈ 19.87%). Allocating 64 seats (64/318 ≈ 20.12%) would exceed it.

Table 1 illustrates:

| District Seats | Party-List Seats | Total Seats | 20% of Total | Compliant? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 254 | 63 | 317 | 63.4 | Yes |

| 254 | 64 | 318 | 63.6 | No |

COMELEC’s 63-seat allocation is constitutionally sound, and the OFW Party-list’s rounding argument doesn’t hold up against BANAT’s clear precedent. Their claim here is a legal non-starter, but it’s a symptom of deeper frustrations.

The Banat Formula: Fair or Fatally Flawed?

The petition takes aim at the “Banat” formula, arguing it disproportionately favors well-funded groups that clear the 2% vote threshold under Republic Act No. 7941 (Party-List System Act). Established in BANAT v. COMELEC, the formula works in two steps:

- Parties with ≥2% of total party-list votes get one guaranteed seat.

- Remaining seats are distributed proportionally based on vote shares, capped at three seats per party.

The OFW Party-list contends this setup sidelines smaller sectoral groups, like those representing overseas Filipino workers (OFWs). They’re not entirely wrong. Larger, resource-rich parties—often backed by political dynasties or corporate interests—can dominate the guaranteed seats, leaving scraps for smaller players. But BANAT ensures smaller parties aren’t entirely shut out: those below 2% can still snag additional seats if slots remain after the initial allocation, as seen in the 2019 party-list results.

Consider a hypothetical (Table 2):

| Party | Vote Share | Guaranteed Seats (≥2%) | Additional Seats | Total Seats |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party A | 6% | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Party B | 3% | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Party C | 1.5% | 0 | 1 (if slots left) | 1 |

In this scenario, Party C (a smaller sectoral group) still gets a seat, but Party A’s dominance highlights the formula’s bias toward bigger players. The three-seat cap, meant to prevent monopolies, doesn’t fully level the playing field when well-funded groups can mobilize votes more effectively. The formula is legally valid—BANAT is binding precedent—but its fairness is questionable when resource disparities skew outcomes. COMELEC’s discretion to apply it, per RA 7941, Section 11, is broad, but the OFW Party-list’s call for reform raises a valid point: the system rewards political muscle over marginalized voices.

Marginalized Sectors or Masquerading Elites?

The petition’s most provocative claim is that the party-list system, designed under RA 7941, Section 2 to uplift “marginalized and underrepresented” sectors, has been hijacked by powerful interests. This isn’t just rhetoric—it’s a systemic flaw exposed in Atong Paglaum v. COMELEC (G.R. No. 203766, 2013). The Supreme Court ruled that sectoral parties must represent marginalized groups (e.g., OFWs, farmers), but national and regional parties face no such requirement. This loophole lets well-heeled groups—think business tycoons or political dynasties—pose as “sectoral” champions, flooding the system with proxies.

The OFW Party-list’s grievance resonates here. OFWs, remitting over $30 billion annually to the Philippine economy, are undeniably marginalized, lacking political clout despite their economic weight. Yet, parties linked to entrenched elites often secure seats, diluting the system’s purpose. Atong Paglaum tasked COMELEC with stricter accreditation to weed out impostors, but enforcement remains spotty. RA 7941’s vague criteria for “marginalized” status and COMELEC’s inconsistent gatekeeping let groups with dubious credentials slip through, undermining the constitutional intent.

Ethical Breaches: COMELEC’s Blind Spots

Under Republic Act No. 6713 (Code of Conduct for Public Officials), COMELEC officials must uphold fairness and accountability. The OFW Party-list’s petition implies ethical lapses in COMELEC’s failure to curb non-marginalized groups and its rigid adherence to the Banat formula. While no direct evidence of corruption surfaces in the petition, the systemic issue—allowing business interests or dynastic proxies to infiltrate the party-list system—raises red flags. COMELEC’s accreditation process, which should scrutinize nominees’ ties to marginalized sectors, often seems more performative than rigorous. This isn’t just a procedural hiccup; it’s a betrayal of public trust, as RA 6713 demands “justness and sincerity” in public service.

Preempting COMELEC’s Defense

COMELEC will likely argue it has statutory discretion under RA 7941 to allocate seats and accredit parties. They’re not wrong—BANAT and Atong Paglaum grant them wiggle room. But discretion isn’t a blank check. Under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court, the OFW Party-list must prove grave abuse of discretion—a high bar. The 63-seat allocation aligns with BANAT, and the formula’s application follows precedent, so their certiorari petition faces an uphill battle. Still, their broader critique of systemic hijacking could justify a TRO if they can show irreparable harm to marginalized sectors’ representation. The Supreme Court might not strike down Resolution 14-25 but could nudge COMELEC toward stricter accreditation.

Recommendations: Fixing a Broken System

The OFW Party-list’s petition, while shaky on the 63-seat claim, exposes real flaws. Here’s how to fix them:

- Legislative Reform: Amend RA 7941 to tighten “marginalized” criteria, requiring clear evidence of sectoral ties (e.g., OFW nominees must have verifiable overseas work history).

- Stricter COMELEC Accreditation: Enforce Atong Paglaum’s mandate with transparent, rigorous reviews to disqualify proxy parties.

- Formula Tweak: Lower the 2% threshold or prioritize additional seats for sectoral parties to balance resource disparities.

- Judicial Oversight: The Supreme Court should clarify Atong Paglaum’s loopholes, perhaps via a new ruling defining “marginalized” more stringently.

Conclusion: A System Betrayed

The OFW Party-list’s petition may falter on technical grounds—63 seats is constitutional, and the Banat formula is legally sound. But their cry of betrayal rings true. When OFWs, farmers, and indigenous groups compete with dynastic proxies and corporate-backed parties, the party-list system isn’t just flawed—it’s a farce. COMELEC’s math may add up, but its failure to guard the system’s soul doesn’t. The Supreme Court should use this case to signal reform, and Congress must act to close loopholes. Until then, the marginalized will remain on the sidelines, their voices drowned out by the very elites the system was meant to counter.

Key Citations:

- 1987 Constitution, Art. VI, Sec. 5

- Republic Act No. 7941

- Republic Act No. 6713

- BANAT v. COMELEC

- Atong Paglaum v. COMELEC

- Party-List Seat Allocation Explanation

- House of Representatives Composition

Gg

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment