By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — June 1, 2025

WHILE Filipino families grapple with rice prices soaring to ₱60 per kilo, their government has quietly piled on ₱10 trillion in debt over the past decade, a fiscal time bomb now ticking at 61.3% of GDP. For every Filipino—man, woman, and child—that’s ₱48,000 in silent debt, a burden they never voted for but will pay for generations. As hospital wards close and schoolrooms crumble, the question looms: Who will foot the bill when the collectors come knocking—China, the IMF, or the Filipino people themselves?

The Philippines’ debt crisis didn’t erupt overnight. It was built, brick by borrowed brick, under two administrations that promised prosperity but delivered precarity. Under Rodrigo Duterte (2016-2022), the national debt surged by ₱6.89 trillion, nearly doubling from ₱5.9 trillion to ₱12.79 trillion. Ferdinand Marcos Jr., in just 2.5 years since 2022, has added another ₱3.52 trillion, pushing the total to ₱16.31 trillion by January 2025. That’s a 27.5% spike on his watch, outpacing Duterte’s annual average of ₱1.148 trillion with a blistering ₱1.384 trillion per year.

The Duterte Era: A Necessary Tragedy?

Duterte’s tenure began with swaggering promises of a “Golden Age of Infrastructure” through his Build, Build, Build program. Bridges, roads, and airports were to transform the archipelago into an economic powerhouse. By 2019, the debt stood at ₱7.7 trillion, a manageable 39.6% of GDP (Wikipedia). Then COVID-19 hit. The government borrowed ₱2.74 trillion in 2020 alone—more than double the previous year’s haul—to fund ventilators, relief packages, and economic survival. By the time Duterte left office in 2022, the debt-to-GDP ratio had ballooned to 60.9%, teetering on the IMF’s 60% red line.

Leaked Department of Finance (DOF) documents reveal a grim truth: nearly half of the pre-COVID borrowing went to infrastructure projects with questionable returns. A 2021 audit flagged cost overruns on 12 flagship projects, including a ₱50 billion railway with delays stretching to 2027. Interest payments, which hit ₱451 billion by 2022, began crowding out health and education budgets. In Manila’s public hospitals, nurses like Susan Fuentes, 34, saw the fallout firsthand. “We had no PPE, no ventilators,” she told me, her voice cracking. “Now I work triple shifts to afford my son’s school fees because the hospital can’t hire more staff.”

Marcos Jr.’s Double Jeopardy

When Marcos Jr. took office in June 2022, he inherited a battered economy and a weakened peso. His administration faced a double jeopardy: refinancing Duterte’s high-interest pandemic loans while funding new projects to keep the “Golden Age” narrative alive. By January 2025, the debt hit ₱16.31 trillion, with the peso slumping to ₱58.4 per dollar, inflating the cost of foreign loans by ₱1.51 billion in a single month (GMA News).

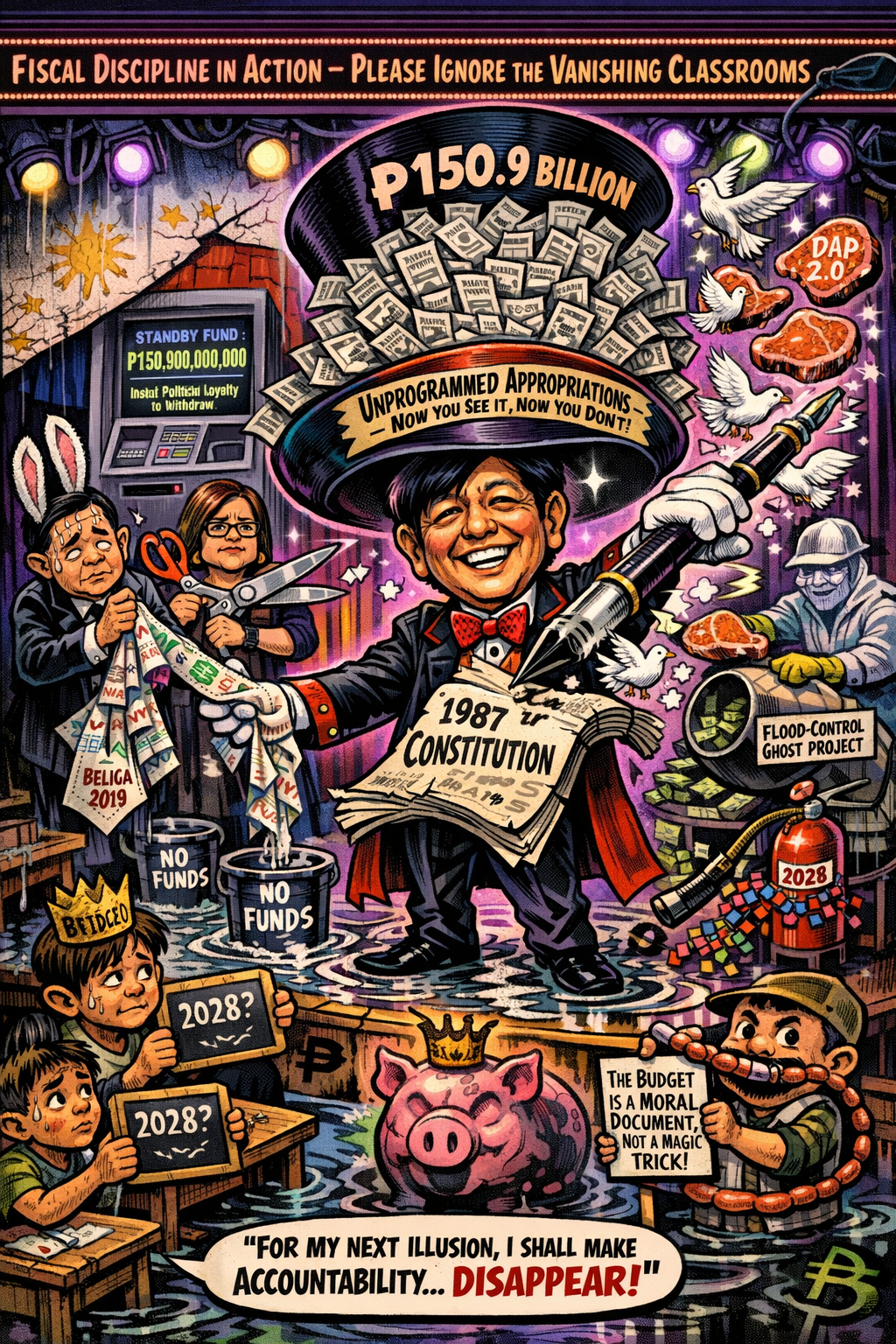

Marcos Jr. pledged “debt transparency,” but deleted Treasury tweets from mid-2024—recovered via web archives—hint at bond issuances that failed to attract investors. The Bureau of the Treasury’s own data shows domestic debt now accounts for 67.9% of the total (₱11.08 trillion), masking reliance on volatile foreign bonds (Wikipedia). Global banks like JPMorgan Chase and HSBC have reaped millions in fees from these refinancing deals, while Filipino taxpayers bear the cost. In 2024 alone, debt service soared to ₱2.02 trillion—a 26% jump from 2023—devouring funds that could have built 20,000 classrooms or 500 rural health centers.

The human toll is stark. Susan, the nurse, now spends 70% of her income on rent and food, her dreams of saving for her son’s college evaporating. “The government says the economy is growing,” she said, “but my patients are dying because we can’t afford medicine.” In 2025, every ₱100 in taxes will see ₱13.70 vanish into debt service, according to the DOF’s own budget breakdown (DOF). That’s money not reaching Susan’s hospital or the 1 in 3 Filipinos living below the poverty line.

A Structural Betrayal

The Philippines’ debt crisis isn’t just about numbers—it’s a betrayal of trust. Under Duterte, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) warned against high-interest foreign loans, yet officials approved them anyway. A 2020 DOF memo, obtained through a whistleblower, shows then-Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III pushed for $2.5 billion in Eurobonds at 3.75% interest despite cheaper domestic options. Under Marcos Jr., Finance Secretary Ralph Recto has continued the trend, signing off on $1.5 billion in samurai bonds in 2024 at rates 0.5% higher than Tokyo’s benchmark.

The real crisis looms on the horizon. The IMF’s 60% debt-to-GDP threshold is a warning siren, and at 61.3% in 2024 (Wikipedia), the Philippines is already in the danger zone. If global interest rates rise further or the peso weakens to ₱60/$, debt service could hit ₱2.5 trillion by 2027, consuming nearly a fifth of the budget. The irony is biting: Marcos Jr.’s administration touts fiscal discipline while quietly refinancing Duterte’s debts at higher costs, with little transparency on where the money goes.

The China Question and the IMF Shadow

Foreign creditors cast a long shadow. China, holding ₱1.2 trillion in Philippine debt through its Belt and Road loans, has pushed for infrastructure projects like the Davao-Samal Bridge, with murky terms that could include resource concessions. A 2023 FOIA request for loan collateral details was denied, citing “national security.” The opacity fuels fears that Manila’s fiscal sovereignty is slipping. Meanwhile, the IMF hovers, ready to impose austerity if the debt spirals further. In 1986, the Philippines bowed to IMF conditions, slashing social spending and sparking protests. History could repeat itself.

A Path Forward: Debt Autopsy and Reform

This crisis demands accountability. First, a Debt Autopsy—a forensic audit of pandemic-era contracts—is essential. The Commission on Audit must probe cost overruns and identify profiteers, from local contractors to foreign banks. Names like Dominguez and Recto should face scrutiny for their loan approvals, as should the BSP for failing to enforce its warnings.

Second, a Debt-to-Development law could tie future borrowing to poverty reduction. For every peso borrowed, an equal amount must fund measurable outcomes: vaccines, classrooms, or microloans for farmers. This would force discipline on a government too quick to borrow for prestige projects.

Finally, transparency must be non-negotiable. Marcos Jr.’s deleted tweets and vague DOF press releases erode trust. A public debt dashboard, updated monthly with loan terms and beneficiaries, could restore accountability.

The Ticking Clock

The Philippines stands at a crossroads. Marcos Jr. projects a debt-to-GDP drop to 56.3% by 2028, but missed growth targets (5.6% actual vs. 6.5% planned in 2024) cast doubt (Inquirer). Susan Fuentes, working her third shift in a crumbling hospital, can’t wait for promises. Neither can the 36 million Filipinos—one in three—whose ₱48,000 share of the debt grows daily.

When the debt collectors come, will it be China demanding ports and reefs, or the IMF with its austerity playbook? The answer depends on whether Manila can confront its fiscal recklessness before the bomb detonates.

The Philippines’ Debt Spiral

A fiscal crisis threatens Filipino families

₱16.31T Total Debt (Jan 2025)

Debt doubled in a decade.

₱48,000 Per Filipino

Enough to buy 800 kilos of rice.

Key Creditors

JPMorgan Chase, HSBC, China (₱1.2T)

Foreign banks profit from high-interest loans.

Data Gaps

*FOIA needed for Chinese loan terms

Opaque contracts hide potential concessions.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

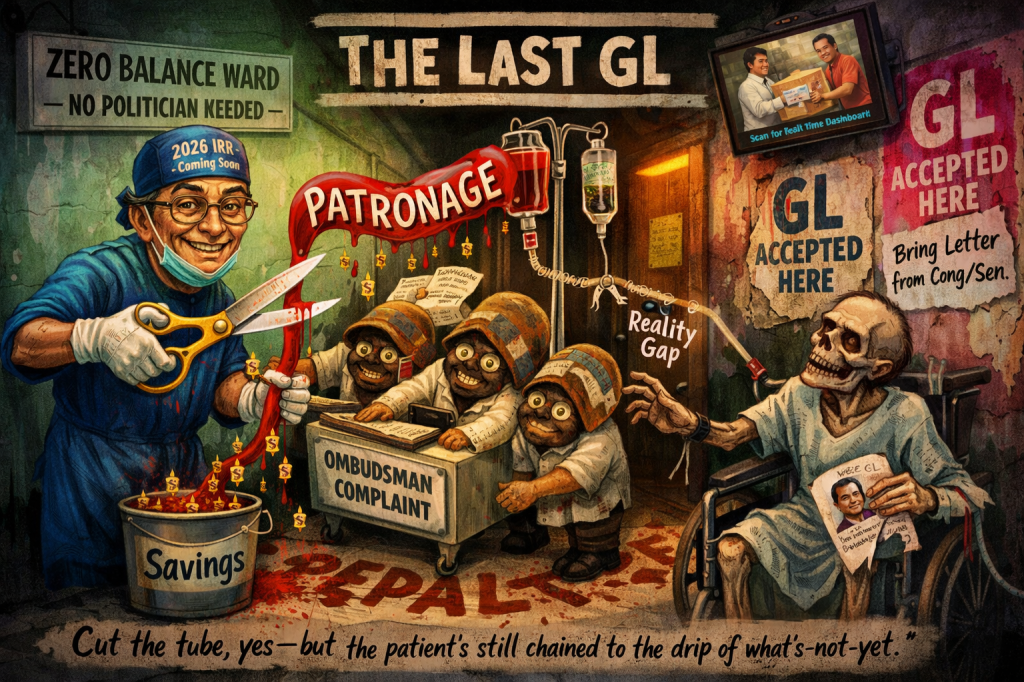

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

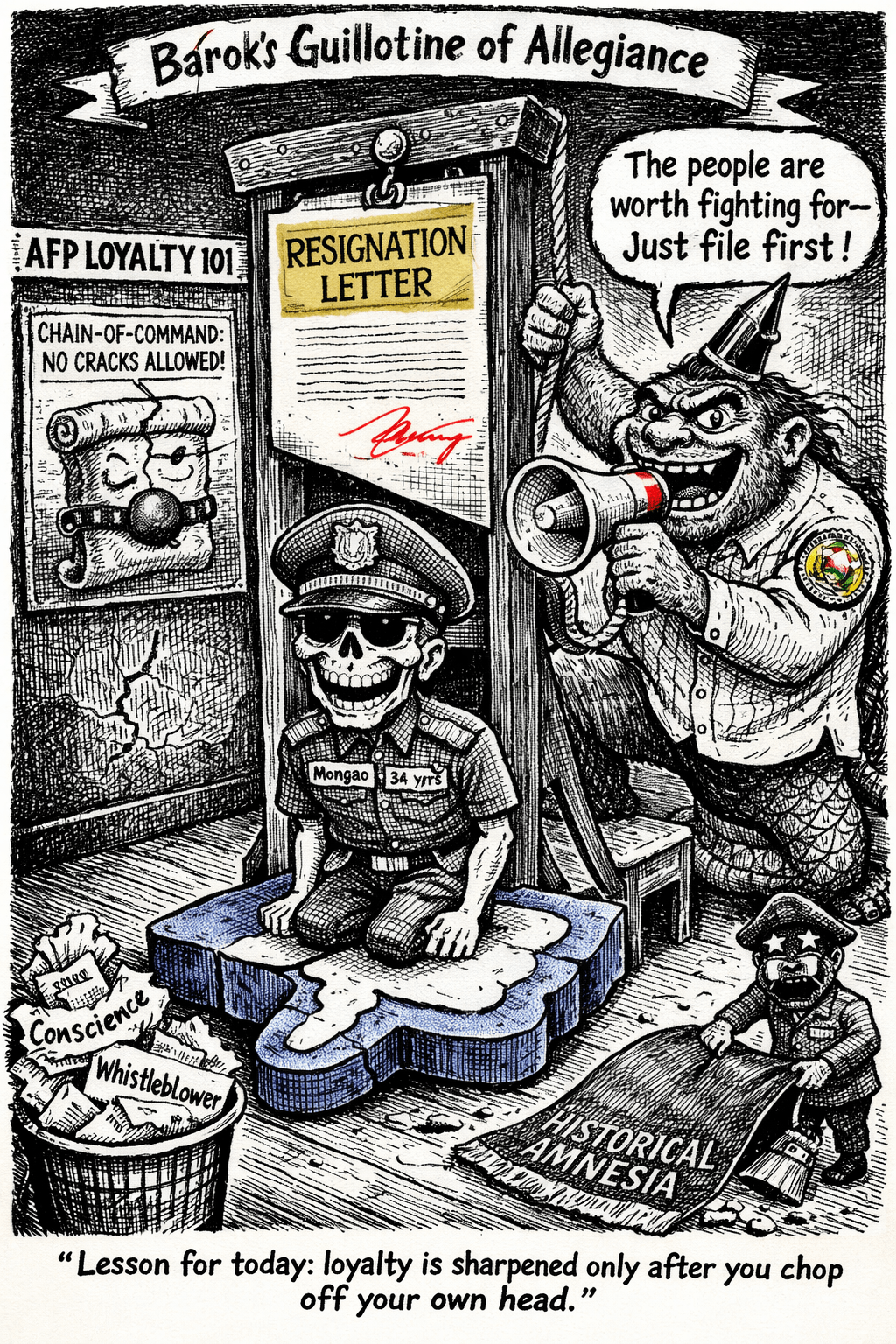

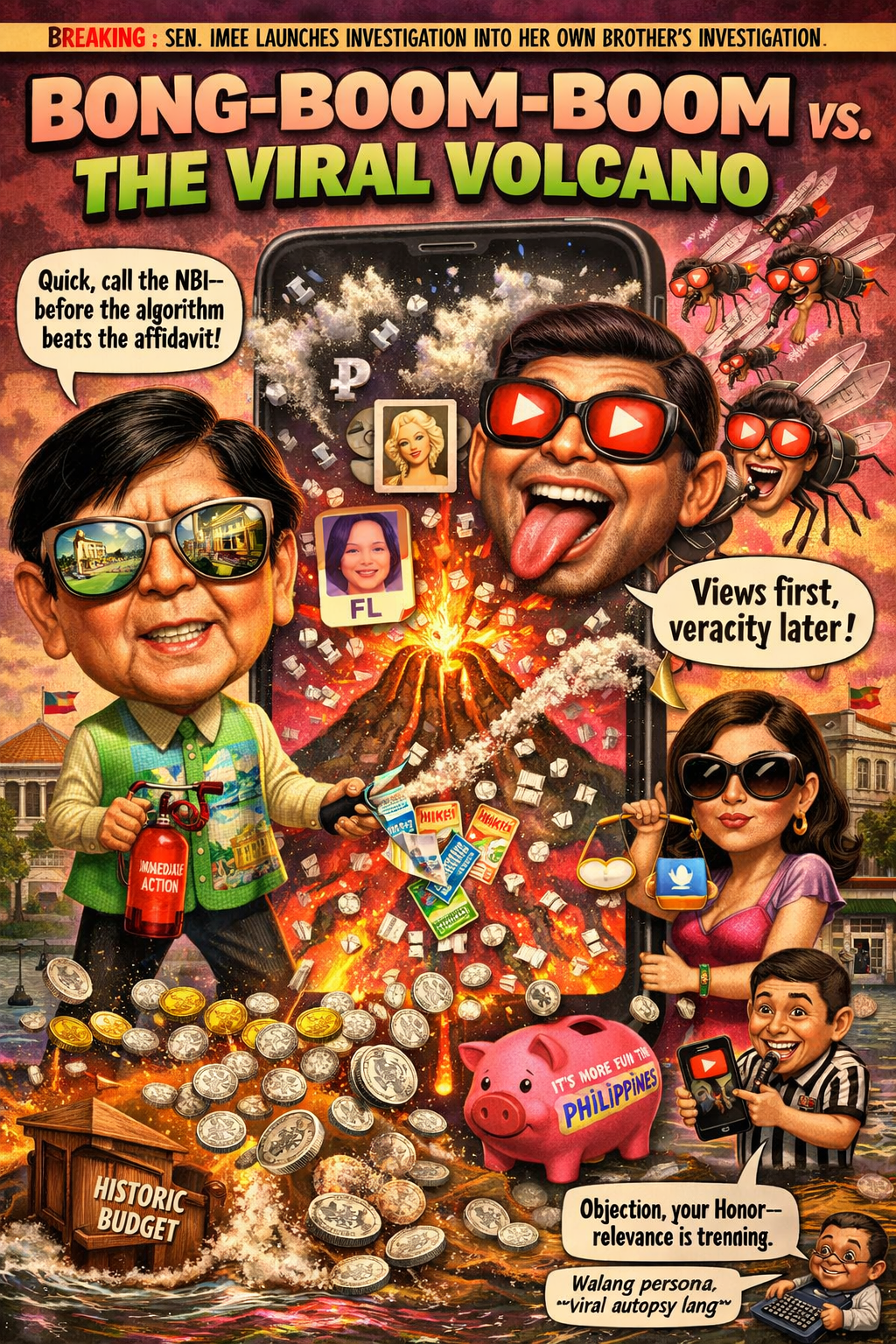

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

- “Allocables”: The New Face of Pork, Thicker Than a Politician’s Hide

- “Ako ’To, Ading—Pass the Shabu and the DNA Kit”

Leave a comment