By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — June 5, 2025

The Farmer’s Last Hope

The Farmer’s Last Hope

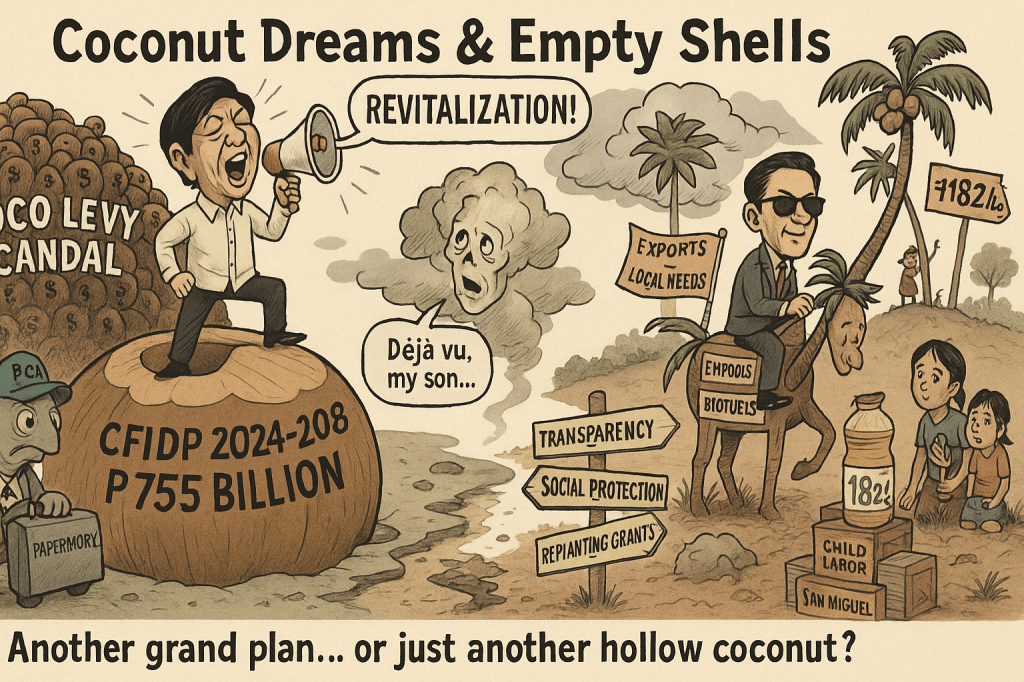

FOR Marla Cantos, a 42-year-old coconut farmer in Leyte, the promise of a “revitalized” industry feels like a cruel echo of history. Her small plot, barely a hectare, was ravaged by Typhoon Rai in 2021, leaving her family of five teetering on the edge of survival. The nearest Philippine Coconut Authority (PCA) training center is 50 kilometers away—unreachable without costly transport. Now, with President Ferdinand R. Marcos Jr.’s approval of the Coconut Farmers and Industry Development Plan (CFIDP) 2024-2028, hope flickers. But can a P75-billion plan truly lift farmers like Marla from poverty, or will it, like the scandal-ridden coco levy fund of decades past, enrich others while leaving the poorest behind?

Trust Fund or Trust Deficit?

The ghost of the coco levy fund scandal looms large over the CFIDP. In the 1970s and 1980s, coconut farmers were taxed billions—estimates range from P100 billion to P150 billion in today’s value—to supposedly develop the industry. Instead, the funds were siphoned off by Marcos-era cronies, funneled into ventures like the United Coconut Planters Bank and San Miguel Corporation, leaving farmers like Marla’s parents with nothing. A 2012 Supreme Court ruling declared these assets must benefit farmers, yet distrust festers. Past efforts faltered: in 2022, only 8.78% of a P755-million fund for the prior CFIDP was used, with goals like fertilizing 10,676 hectares missing the mark by over 6,000. Why should farmers believe this time will be different? Historical betrayal casts a long shadow, and without ironclad transparency, the P75-billion Coconut Farmers and Industry Trust Fund risks being another mirage.

When ‘Modernization’ Leaves the Poor Behind

Who truly stands to gain from the CFIDP’s push for modernization? The plan’s seven components—spanning hybridization, processing, and community enterprises—sound promising. But smallholders like Marla, often tenants farming less than 2 hectares, face structural barriers. Large agribusinesses, with capital to invest in hybrid trees and processing facilities, are better positioned to tap export markets, the Philippines’ biggest coconut revenue stream. Meanwhile, tenants lack land titles, excluding them from loans or replanting grants. Data underscores the divide: 60% of coconut farmers live below the poverty line, earning pennies per coconut. Will modernization dollars flow to corporate players, or will targeted aid reach the smallest, most vulnerable plots?

Equally troubling is the silence on child labor. Reports expose children toiling in hazardous conditions—climbing trees, hauling heavy loads—for little or no pay. The CFIDP touts social protection and training, yet why does a plan billed as “pro-poor” omit explicit child labor protections? Without monitoring and enforcement, the cycle of poverty—where kids forgo school to help families survive—will persist.

Bureaucracy vs. Urgency

Implementation lags haunt the CFIDP’s promise. The prior plan stumbled when the PCA board’s reconstitution delayed action, leaving goals like training 2,517 personnel short by over 2,300. Now, the need is dire: 100 million aging trees must be replanted by 2028 to reverse a 20% production drop from El Niño and typhoons. Bureaucratic red tape—slow fund releases, poor coordination—threatens this timeline. The P75-billion trust fund sounds substantial, but is it enough? Climate shocks batter yields, and recovery from hybrid trees takes 6 to 10 years. If funds are misallocated or delayed, farmers face a lost decade. How will the PCA, tasked with leading this charge, break from past inertia to deliver urgent relief?

Export Dreams, Domestic Pain

A stark contradiction lies at the CFIDP’s heart: its export focus clashes with domestic need. Coconut products drive billions in revenue, and the plan doubles down on hybridization and processing for global markets. Yet copra prices have soared to P58.10/kg at the farmgate, pushing cooking oil to P172–182/kg—a burden on poor households already squeezed by inflation. Is this a trade-off—bolstering farmer income at the expense of food security? The tension is real: biofuel blends and illegal exports tighten domestic supply, hiking costs for the very communities the plan claims to uplift. And for farmers transitioning to hybrids, the wait for fruit—6 to 10 years—looms large. Where are the income safety nets to bridge this gap? Without them, smallholders risk destitution while waiting for a payoff.

Voices Unheard in Remote Fields

The CFIDP boasts “extensive stakeholder consultations,” but were they meaningful or mere theater? The PCA led forums with farmer groups, yet remote smallholders—lacking roads, transport, or even basic electricity—likely remained sidelined. Marla’s story is telling: no PCA officer has visited her village in years, and training feels like a distant dream. Gaps yawn wide—poor infrastructure isolates farmers from markets, seeds, and skills. The plan’s seven components, from cooperatives to support services, sound robust, but how do they reach the margins? If consultations missed the most isolated, the CFIDP’s promises of empowerment may prove hollow, leaving the poorest to fend for themselves.

A Verdict and a Call to Action

The CFIDP 2024-2028 offers a flicker of hope—training, social protection, and replanting could transform lives if done right. But skepticism is warranted. History screams caution: misused funds, sluggish execution, and structural biases have burned coconut farmers before. The plan’s silence on child labor and weak safety nets for hybrid transitions raise red flags, as does the tug-of-war between exports and local needs. For Marla Cantos and millions like her, the stakes are existential.

Auditors must pounce—track every peso of the P75-billion fund with real-time, public reports. Lawmakers should demand child labor safeguards and income bridges for farmers. Grassroots groups must amplify remote voices, ensuring the PCA hears the marginalized. Only relentless scrutiny can turn this plan from a lofty promise into a lifeline. Will the Philippines finally deliver for its coconut farmers, or is this another chapter of betrayal? The answer lies in action, not words.

Key References

- “Coco Levy Fund Scam.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 4 June 2025.

- Relevance: Chronicles the 1970s-1980s misuse of coconut levy funds by Marcos-era cronies, detailing diversions to ventures like United Coconut Planters Bank and San Miguel Corporation, and the 2012 Supreme Court ruling for farmer benefits—fueling distrust in the CFIDP.

- “Coconut Controversy.” Food Is Power, Food Empowerment Project, 4 June 2025.

- Relevance: Exposes persistent child labor in the coconut industry, with children in hazardous, low-wage work and 60% of farmers below the poverty line, raising questions about the CFIDP’s social protection gaps.

- Doyo, Ma. Ceres P. “New Hope for Coconut Farmers.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 29 Oct. 2023.

- Relevance: Highlights implementation failures of the prior CFIDP, noting only 8.78% of a P755-million fund was used in 2022 and targets like fertilizing 10,676 hectares fell short, underscoring bureaucratic delays.

Leave a comment