By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — June 5, 2025

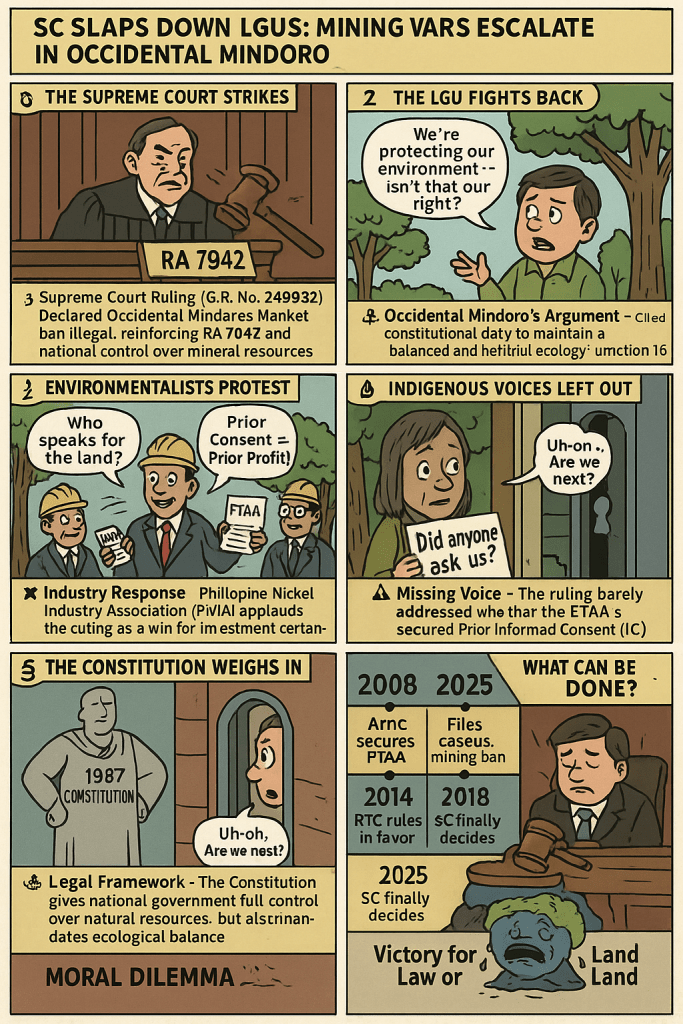

THE Supreme Court’s January 14, 2025, ruling—dropped like a bombshell on May 14—obliterated Occidental Mindoro’s 25-year ban on large-scale mining, cementing the state’s iron-fisted control over mineral riches. Penned by Senior Associate Justice Marvic Leonen in G.R. No. 248932 (SC Decision Summary), the 31-page decision brands the province’s ordinances as illegal overreach, trampling the Philippine Mining Act of 1995 (RA 7942) and the 1987 Constitution. This critique rips into the ruling’s legal guts, its precedent pedigree, the stakeholder firestorm, procedural hiccups, and bold next steps, questioning whether the Court fortified national order or sold out local ecosystems.

1. Legal Showdown: National Might Crushes Local Dreams

The ruling exposes a brutal tug-of-war between national and local power over minerals. RA 7942, the Philippine Mining Act, is the state’s trump card. Section 2 hands the state “full control and supervision” of mineral resources, Section 19 empowers the President to ink Financial or Technical Assistance Agreements (FTAAs) for big mining, and Section 27 demands prior informed consent from indigenous communities. LGUs get a seat at the table to vet projects case-by-case, but the Court ruled Occidental Mindoro’s blanket ban—covering all large-scale mining—was a power grab that violated this setup.

The Local Government Code of 1991 (LGC) draws the battle lines. Section 16 lets LGUs wield “general welfare” powers for environmental protection, and Section 458(a)(1)(vi) allows provinces to issue mineral processing permits. But Section 2(c) chains LGU actions to national laws. The 1987 Constitution’s Article XII, Section 2 doubles down, vesting resource ownership in the state and greenlighting FTAAs, relegating LGUs to bit players.

Occidental Mindoro swung back, citing Article II, Section 16 of the Constitution, which demands a “balanced and healthful ecology.” The province argued its police power, rooted in the LGC’s welfare clause, justified the moratorium to shield its environment. Leonen’s ruling scoffed at this, branding the ban “too broad” for dodging RA 7942’s case-by-case mandate. Environmental safeguards, like Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) under Presidential Decree No. 1586, already exist nationally, making the ban an unlawful overstep. The verdict screams hierarchy: LGUs can nudge, but only within Congress’s playbook.

2. Precedent Powerhouse: The Court Stays in Lockstep

The ruling rides a wave of precedents that exalt national law over local bravado. La Bugal-B’laan vs Ramos (G.R. No. 127882) upheld RA 7942, ruling FTAAs are constitutional tools for state-managed resource extraction, not giveaways. This cements mining as a national game, with LGUs as referees, not rulemakers. Tatel v. The Municipality of Virac (G.R. No. 40243, March 11, 1992) drove the point home: LGU ordinances can’t defy national statutes, a dagger to Occidental Mindoro’s moratorium.

Leonen’s logic mirrors these, stressing RA 7942’s structured process—EIAs, LGU input, project-specific approvals—bars sweeping bans. He warned that such bans upset the “delicate balance” between local and national interests, echoing Magtajas v. Pryce Properties Corp., Inc. (G.R. No. 111097, July 20, 1994), which confined LGUs to delegated powers. The ruling’s precedent alignment is airtight, but it ducks the messier issue of whether RA 7942’s safeguards truly protect local environments—a sore spot for groups like Alyansa Tigil Mina.

3. Stakeholder Storm: Profit vs. Planet

The decision has sparked a stakeholder inferno, pitting economic dreams against ecological dread. Alyansa Tigil Mina, an anti-mining coalition, cried foul, lamenting the ruling’s blow to local autonomy and biodiversity. National Coordinator Jaybee Garganera, quoted in Rappler on May 15, 2025 Rappler Report, urged a pivot to “biodiversity protection and climate resilience” within LGU powers. Their ethical jab lands hard: does national control sideline communities facing mining’s scars? Kalikasan People’s Network, in a May 14 statement Kalikasan Post, flagged mining’s dark legacy—deforestation, pollution, rights abuses—amplifying these fears.

On the flip side, the Philippine Nickel Industry Association (PNIA) cheered the ruling as a beacon of “investment clarity,” per a May 16 BusinessMirror post BusinessMirror Article. Aligned with President Marcos Jr.’s 2022 moratorium lift, the industry sees a path to economic growth. This profit-planet clash mirrors global resource battles, where short-term cash often overshadows long-term sustainability.

Palawan’s 50-year moratorium on new mining, enacted March 2025 and hailed by Alyansa Alyansa Statement, now teeters. Though not directly struck, the ruling’s logic—case-by-case over blanket bans—puts Palawan’s policy in the crosshairs. LGUs dreaming of broad prohibitions face a stark warning: tailor tight or face the Court’s axe.

4. Procedural Potholes: A Seven-Year Slog

The case’s timeline—a seven-year grind from Agusan Petroleum and Mineral Corporation’s (APMC) 2014 RTC challenge to the 2025 SC ruling—lays bare the Philippines’ creaky legal system. APMC’s 2008 FTAA, spanning 46,050 hectares across Mindoro, hit a wall with Occidental Mindoro’s moratorium. The RTC’s 2018 pro-APMC ruling took four years, and the SC’s verdict another three, a pace that spooks investors. The PNIA’s enthusiasm for regulatory clarity, noted in Philstar on May 16 Philstar Report, gets dampened by this reality: justice delayed is investment denied.

The ruling skims over RA 7942’s Section 27 “prior informed consent” (PIC) requirement. Leonen nodded to LGUs’ role in vetting projects, including blocking those flouting indigenous rights. But the decision sidesteps whether APMC’s FTAA met PIC standards, a gap that fuels community mistrust. This omission, in a ruling laser-focused on the ban’s overbreadth, leaves a critical safeguard under-scrutinized, risking further unrest.

5. Battle Plan: Outsmarting the Ruling

LGUs must play smarter within RA 7942’s cage:

- EIA Hardball: Block projects failing stringent environmental or social tests, using LGC Section 16’s welfare powers.

- Surgical Ordinances: Craft laser-focused regulations on specific mining harms, dodging RA 7942’s preemption, as Palawan’s moratorium tries.

Congress needs to douse the fire. RA 7942’s Section 19, listing “areas prohibited by law,” is a vague landmine. Amending it to clarify LGU roles—perhaps granting explicit case-by-case veto power—could curb lawsuits. The People’s Mining Bill, pushed by Alyansa Alyansa Advocacy, offers a bolder fix, centering community consent and green priorities to counter RA 7942’s corporate tilt.

Mining firms can’t coast. Adopting beyond-compliance sustainability, like the Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM) standards cited by the Chamber of Mines COMP Standards, is critical. Robust community dialogues, transparent EIAs, and rehabilitation funds can blunt opposition, aligning with the Constitution’s Article II, Section 16 call for ecological balance.

Final Blow: Order Upheld, Justice on Trial

The Supreme Court’s ruling is a legal juggernaut, rooted in RA 7942, the LGC, and the 1987 Constitution, with precedents like La Bugal-B’laan and Tatel as its backbone. It rightfully checks LGU overreach, ensuring national policy steers resource extraction. But it risks muffling local cries and ecological red flags, as Alyansa Tigil Mina warns. Procedural blind spots, like the hazy handling of prior informed consent, and a seven-year court slog expose deeper cracks. LGUs, Congress, and industry must innovate—through precision, reform, and ethics—to bridge the gaping divide between profit and planet.

Key Citations

- SC Decision Summary

- Rappler Report

- Philstar Report

- BusinessMirror Article

- La Bugal-B’laan v. Ramos (G.R. No. 127882)

- Tatel v. The Municipality of Virac (G.R. No. 40243, March 11, 1992)

- Magtajas v. Pryce Properties Corp., Inc. (G.R. No. 111097, July 20, 1994)

Disclaimer: This is legal jazz, not gospel. It’s all about interpretation, not absolutes. So, listen closely, but don’t take it as the final word.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment