By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — June 24, 2025

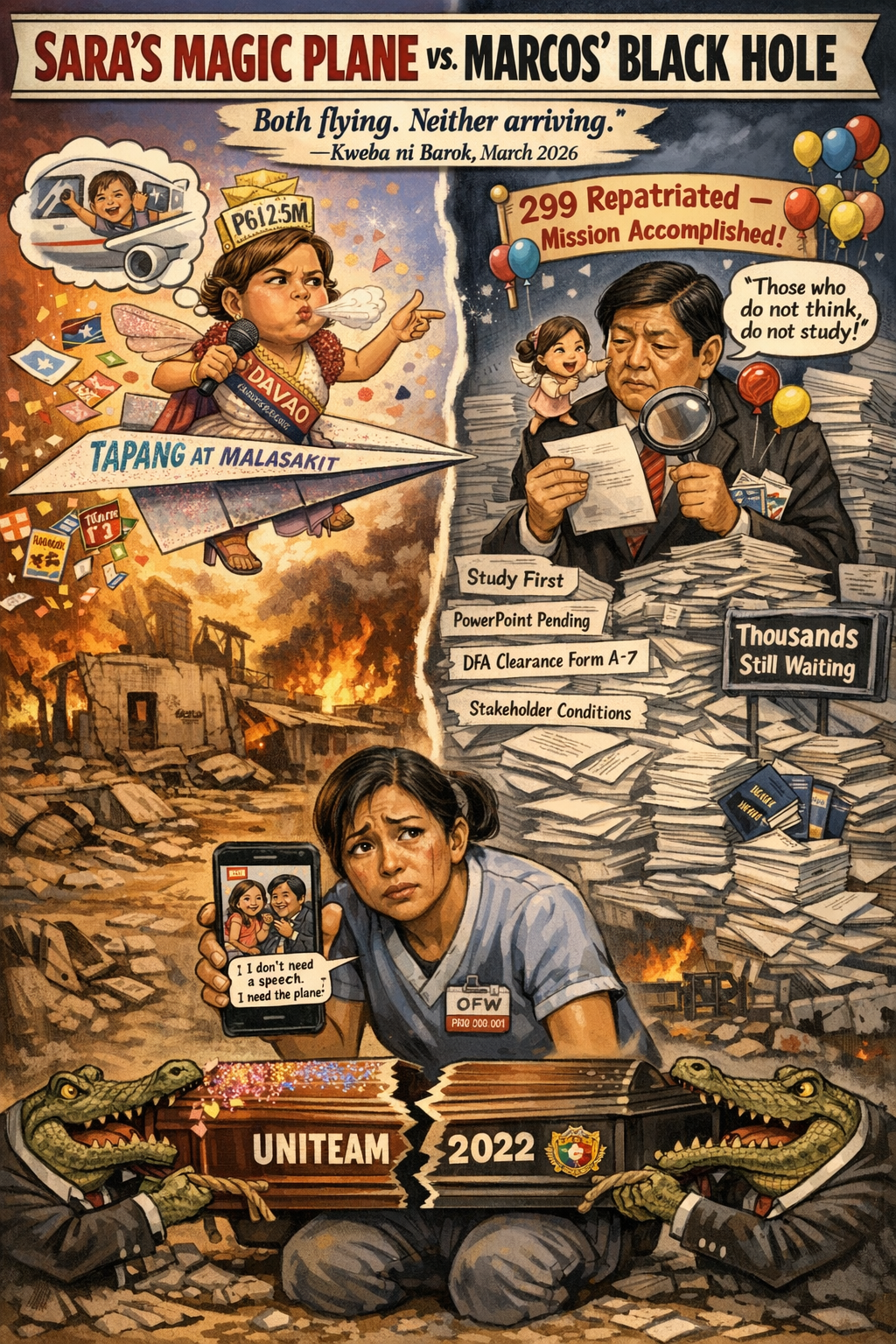

“Vice President Sara Duterte is scared,” declares Leila de Lima, her voice crackling with conviction. The former senator, now a Mamamayang Liberal representative, casts Duterte’s frequent overseas trips—most recently to Australia—as a desperate bid to evade an impeachment trial that threatens to expose her alleged misuse of P612.5 million in confidential funds. Duterte’s itinerary, De Lima argues, reads less like a leader’s calendar and more like a fugitive’s escape plan. But is this a calculated dodge, or a legitimate defense against a politically charged prosecution? The answer could determine not just Duterte’s fate, but the resilience of Philippine democracy itself.

The impeachment saga, rooted in Article XI of the 1987 Constitution, hinges on allegations of graft and betrayal of public trust. The House of Representatives, wielding its exclusive power to initiate impeachment, has accused Duterte of funneling funds to dubious recipients, including one “Mary Jane Piattos.” With 16 defense lawyers at her side, Duterte’s camp has mounted a multi-pronged strategy: engaging the Ombudsman’s June 20 order to respond to complaints, timing overseas rallies with key Senate deadlines, and leveraging a Senate remand of the articles just days before Congress adjourned on June 14, 2025. De Lima calls these maneuvers a pattern of delay, designed to bury evidence and erode public scrutiny. “The public may never see the evidence—unless the Senate acts,” she warns.

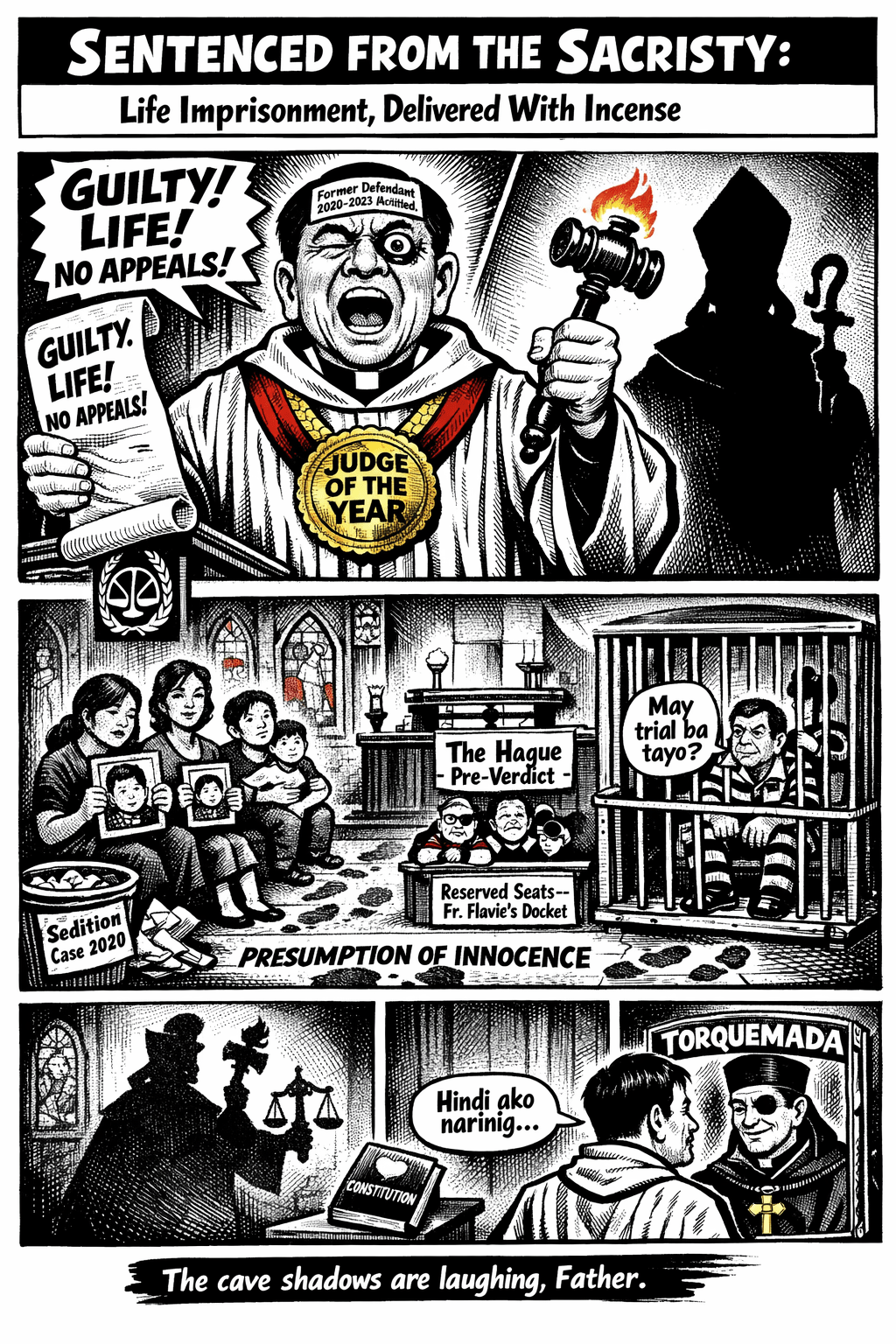

De Lima’s claims carry weight. The Senate’s decision to remand the articles, citing a need for “clarifications,” raises eyebrows given the Constitution’s mandate to proceed “forthwith” (Article XI, Sec. 3(6)). The timing—three days before sine die adjournment—suggests a stalling tactic, especially when paired with Duterte’s absence during critical proceedings. Her Australian rally, framed as a call to “Bring former President Duterte home,” feels like a defiant distraction from her duty to face trial. The Ombudsman’s sudden pivot, under Duterte appointee Samuel Martires, from dismissing earlier probes to launching a preliminary investigation, fuels suspicions of coordination. When officials weaponize procedure, democracy bleeds.

Yet Duterte’s defenders argue she’s exercising her rights. Engaging the Ombudsman, they say, is a constitutional obligation, not a ploy—Republic Act No. 6770 mandates responses to complaints. Overseas trips could be legitimate, tied to her role or political base-building. The Senate’s remand, per Senate President Escudero, prioritizes legislative duties and over 200 pending appointments, not Duterte’s protection. The Ombudsman’s independence, enshrined in Article XI, Sec. 5, shields it from accusations of bias, and its process doesn’t legally preempt the Senate’s trial. Duterte’s due process, they insist, demands rigorous procedural scrutiny, not a rush to judgment.

Both sides have merit, but the stakes transcend legal niceties. The controversy undermines public trust in institutions meant to hold power accountable. When senators like Ronald dela Rosa push for dismissal before trial or publicly endorse Duterte as the next president, they violate Senate Rule 18 and the Code of Judicial Conduct’s call for impartiality. Such breaches echo the 2011 Gutierrez v. House case, where the Supreme Court upheld impeachment’s political nature but demanded basic fairness. If senators act as Duterte’s shield, they risk turning the Senate into a partisan circus, not an impartial court.

The Ombudsman’s role adds another layer of intrigue. Its investigation, while independent, could muddy the impeachment process. A dismissal might embolden Duterte’s camp to challenge the Senate’s jurisdiction, though precedents like Gutierrez affirm impeachment’s autonomy. Parallel proceedings—Ombudsman for criminal liability, Senate for removal—aren’t inherently conflicting, but their timing smells of strategy. Martires’ ties to the Duterte family don’t help. If the Ombudsman’s probe delays or derails the trial, it sets a dangerous precedent: high officials could exploit administrative processes to dodge constitutional accountability.

The impacts ripple beyond Duterte. Public faith in the Senate’s impartiality is fraying, with polls showing declining trust in Congress (Pulse Asia, 2025). Duterte’s rallies abroad, while legal, contrast starkly with her obligation to face vetted witnesses like those cited in the House’s report. This dissonance fuels cynicism, suggesting accountability bends for the powerful. Future impeachments may suffer if delay tactics become normalized, weakening Article XI as a check on abuse. President Marcos’ silence, distancing himself from the fray, raises questions about leadership in a crisis of democratic norms.

Reforms are urgent. The Senate must enforce stricter ethics rules, mandating inhibition for senators showing bias, as voluntary “delicadeza” has failed. The Ombudsman needs transparency protocols to avoid perceptions of political meddling—public timelines for investigations would help. Congress should clarify Article XI’s “forthwith” clause to bar procedural remands that stall trials. Above all, civil society and media must hold institutions accountable, demanding transparency over political theater.

The Philippines stands at a crossroads. Will the Senate uphold its constitutional duty, or enable evasion? Duterte’s fate hinges on evidence, but the nation’s democratic health depends on process. History judges not just the accused, but those who let accountability slip through their fingers. The public watches, waiting for justice—or its betrayal.

Key Citations

- The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines – Article XI | Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines

- Impeachment in the Philippines – Detailed Overview and Historical Context

- ACT NO. 6770 – Functional and Structural Organization of the Office of the Ombudsman

- Office of the Ombudsman – Powers, Functions, and Duties in the Philippines

- What is impeachment and how does it work in the Philippines? | GMA News Online

- G.R. NO. 146486 – Office of the Ombudsman vs. Court of Appeals and Former Deputy Ombudsman

- Office of the Ombudsman (Philippines) – Historical and Legal Background

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment