By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — July 5, 2025

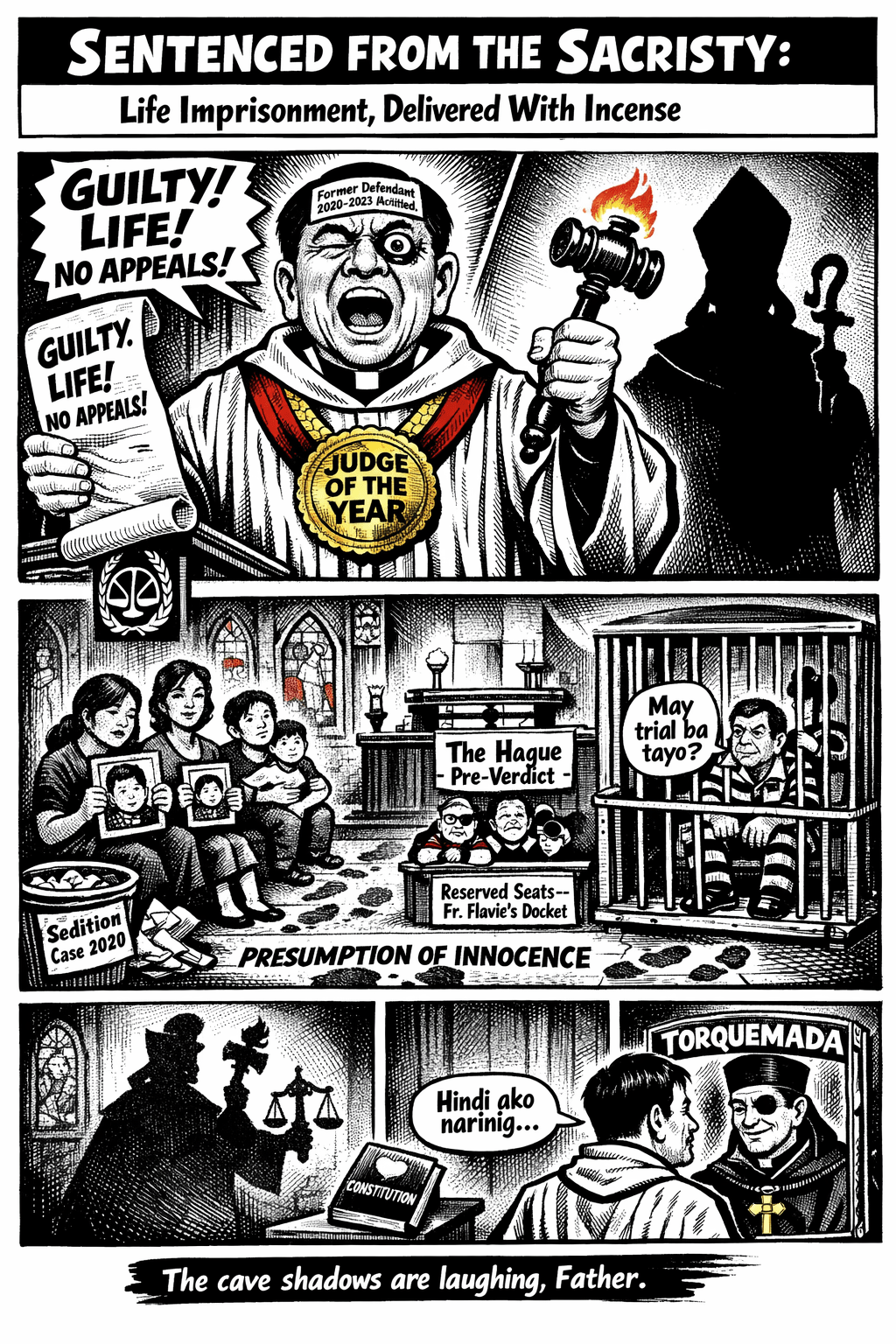

SENATE President Chiz Escudero’s loose lips aren’t just bending Senate rules—they’re setting fire to the constitutional mandate of the Sara Duterte impeachment trial. Former Justice Antonio Carpio’s blistering critique exposes a chilling truth: Escudero’s procedural ploys are a thinly veiled shield for Duterte, cloaked in flimsy precedent and political gamesmanship.

Torching the Rules: Escudero’s Arguments Gutted

Gutierrez Precedent: A House of Cards Collapses

Escudero’s reliance on the 2011 Merceditas Gutierrez impeachment dismissal as precedent is a legal mirage. Carpio dismantles this with surgical precision, noting that Gutierrez’s resignation rendered her trial moot, as impeachment jurisdiction applies only to sitting officials (1987 Constitution, Art. XI, Sec. 3(6)). The Supreme Court’s ruling in Gutierrez v. House of Representatives (G.R. No. 193459, 2011) confirms resignation ends the process—unlike Sara Duterte, who remains defiantly in office. Escudero’s attempt to equate the two cases is a hollow dodge, contradicted by Francisco v. House of Representatives (G.R. No. 160261, 2003), which mandates the Senate to “try and decide” impeachment cases. His precedent is no shield—it’s a smokescreen.

Gag Rule Defiance: Escudero’s Reckless Grandstanding

Escudero’s June 25 press conference, where he challenged Carpio and justified returning the impeachment articles, obliterates Rule 18 of the Senate Rules of Procedure Governing Impeachment Trials (PDF): “The presiding officer and the senator-judges shall refrain from commenting on the merits of a pending impeachment case.” Carpio’s rebuke is ironclad—Escudero’s remarks, even if framed as procedural, taint the trial’s impartiality by signaling bias. The gag rule exists to preserve the Senate’s role as an impartial court, not a political stage. Escudero’s defiance doesn’t just flirt with impropriety; it’s a brazen assault on due process, risking the trial’s legitimacy (Corona v. Senate, G.R. No. 200242, 2012).

Ethical Abyss: Carpio’s Restraint vs. Escudero’s Power Play

Escudero’s jab at Carpio’s silence during the Gutierrez case is a desperate misfire. As a sitting Supreme Court Justice in 2011, Carpio was bound by Canon 3 of the New Code of Judicial Conduct for the Philippine Judiciary (A.M. No. 03-05-01-SC), which demands impartiality and bars commentary on cases that could reach the Court. His silence was ethical duty, not selective outrage. Escudero, as presiding officer, faces no such judicial constraint but is explicitly bound by Senate Rule 18. His press conference was a calculated flex, not a lapse, undermining the Senate’s credibility as an impartial arbiter.

Legal Arsenal Unleashed: Precedents That Crush Escudero’s Case

Senate’s Duty: No Constitutional Escape Hatch

The 1987 Constitution, Art. XI, Sec. 3(6) vests the Senate with the “sole power to try and decide” impeachment cases. Estrada v. Desierto (G.R. Nos. 146710-15, 2001) underscores this as a non-discretionary mandate—once the House transmits articles, the Senate must act. The 18-5 vote to return the case, led by Duterte allies like Senators Dela Rosa and Cayetano, reeks of political sabotage. This maneuver defies the Senate’s constitutional duty, setting a dangerous precedent where procedural nitpicking can derail accountability.

Contempt Power: A Dormant Sword Ignored

Rule VII of the Senate Impeachment Rules (PDF) empowers the impeachment court to hold violators in contempt for breaching its rules. Escudero’s prejudicial comments—questioning the case’s validity and Carpio’s credibility—could trigger sanctions. Yet, the Senate’s silence reveals a glaring double standard. If a senator-judge like Hontiveros made pro-impeachment remarks, contempt motions would likely swarm. The court’s refusal to discipline its presiding officer exposes bias, eroding its legitimacy (Corona v. Senate, 2012).

Bank Records Subpoena: Escudero’s Obstruction Unmasked

Carpio’s demand to subpoena Duterte’s bank records is legally ironclad. Marquez v. Desierto (G.R. No. 135882, 2001) affirms the power to compel disclosure in corruption probes, reinforced by Section 8 of Republic Act No. 6770 (Ombudsman Act). Escudero’s delay tactics—returning the case instead of issuing subpoenas—smack of obstruction, shielding Duterte from scrutiny over alleged fund misuse. This stonewalling stalls justice and fuels suspicions of a political cover-up.

Ticking Time Bomb: A Constitutional Crisis Looms

Political Charade: Trial Turned Travesty

Escudero’s alignment with Duterte loyalists, evidenced by Dela Rosa’s dismissal motion and Cayetano’s amendment, transforms the impeachment court into a political circus. The 18-5 vote to punt the case back to the House isn’t procedural prudence—it’s a calculated move to protect Duterte. This risks turning a constitutional process into a farce, eroding public faith in accountability (Corona v. Senate, 2012).

2028 Election Gambit: Duterte’s Path Paved

The trial’s derailment is a chess move for 2028. A stalled or dismissed impeachment bolsters Sara Duterte’s presidential bid, letting her evade accountability for alleged corruption. Early 2028 polls position her as a frontrunner; a Senate that shields her now effectively endorses her candidacy. Escudero’s actions, wittingly or not, tilt the electoral scales, subverting democratic fairness.

Public Trust: Poisoned by Partisanship

Impeachment hinges on perceived fairness (Corona v. Senate, 2012). Escudero’s public comments and the Senate’s procedural stalling taint this perception, casting senator-judges as Duterte’s defenders, not impartial arbiters. Amid the Marcos-Duterte feud, public trust—already fragile—risks collapsing if the trial is seen as a sham. The Senate’s failure to enforce its own rules signals that in the Philippines, impeachment is just another word for impunity.

Verdict Delivered: Restoring Justice or Risking Collapse

For the Senate: Stop the Sabotage

- Sanction Escudero: Enforce Rule / System: 18 with contempt proceedings for Escudero’s gag rule violation. Impartiality demands accountability, starting at the top.

- Subpoena Bank Records: Issue subpoenas immediately, per Marquez v. Desierto (2001) and RA 6770, to probe Duterte’s alleged fund misuse. Transparency is non-negotiable.

- Proceed with the Trial: Honor the constitutional mandate (Estrada v. Desierto, 2001). Returning the case was a dodge; the Senate must try and decide, not delay.

For the Public: Demand Accountability

Watch the senators’ votes—they’re not just judging Sara Duterte; they’re carving their own political epitaphs. Demand transparency and fairness, or the impeachment process becomes a tool for the powerful, not the people.

For the Supreme Court: Brace for Intervention

Francisco v. House (2003) looms large. If the Senate persists in abdicating its duty, judicial review for grave abuse of discretion is inevitable. The Court must be ready to uphold the Constitution over political games.

Escudero’s precedent? A crumbling facade. The real precedent being set is this: when power protects power, justice becomes the casualty. The Senate must act, or the nation risks a constitutional crisis where accountability is a distant memory.

Justice on Trial: Will the Senate Save or Sink Philippine Democracy?

The Sara Duterte impeachment trial teeters on the edge of a constitutional abyss, where Senate President Chiz Escudero’s defiance of rules and precedent threatens to reduce a sacred accountability mechanism to a political charade. Carpio’s clarion call for impartiality and transparency is not just a legal rebuke—it’s a warning that the Senate’s inaction could enshrine impunity as the true victor. If the Senate fails to enforce its own rules, subpoena critical evidence, and fulfill its constitutional duty, it will not only shield Duterte but also betray the public’s trust, paving the way for a future where power trumps justice. The choice is stark: uphold the rule of law or let impeachment become a hollow relic of Philippine democracy.

Key Citations

- 1987 Constitution, Art. XI, Sec. 3(6): Mandates the Senate’s sole power to try and decide impeachment cases.

- Gutierrez v. House of Representatives, G.R. No. 193459, 2011: Clarifies that resignation moots impeachment proceedings.

- Francisco v. House of Representatives, G.R. No. 160261, 2003: Affirms the Senate’s duty to try impeachment cases and the Court’s review power for grave abuse.

- Estrada v. Desierto, G.R. Nos. 146710-15, 2001: Emphasizes the Senate’s non-discretionary duty to act on impeachment articles.

- Corona v. Senate, G.R. No. 200242, 2012: Upholds Senate autonomy but stresses fairness in impeachment trials.

- Marquez v. Desierto, G.R. No. 135882, 2001: Supports compelled disclosure of bank records in corruption probes.

- Senate Rules of Procedure Governing Impeachment Trials, Rule 18: Prohibits public comments on pending impeachment cases.

- New Code of Judicial Conduct for the Philippine Judiciary, Canon 3, A.M. No. 03-05-01-SC: Mandates impartiality and bars judicial commentary on pending cases.

- Republic Act No. 6770, Section 8: Grants subpoena powers, relevant to Duterte’s bank records.

Leave a comment