By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — July 6, 2025

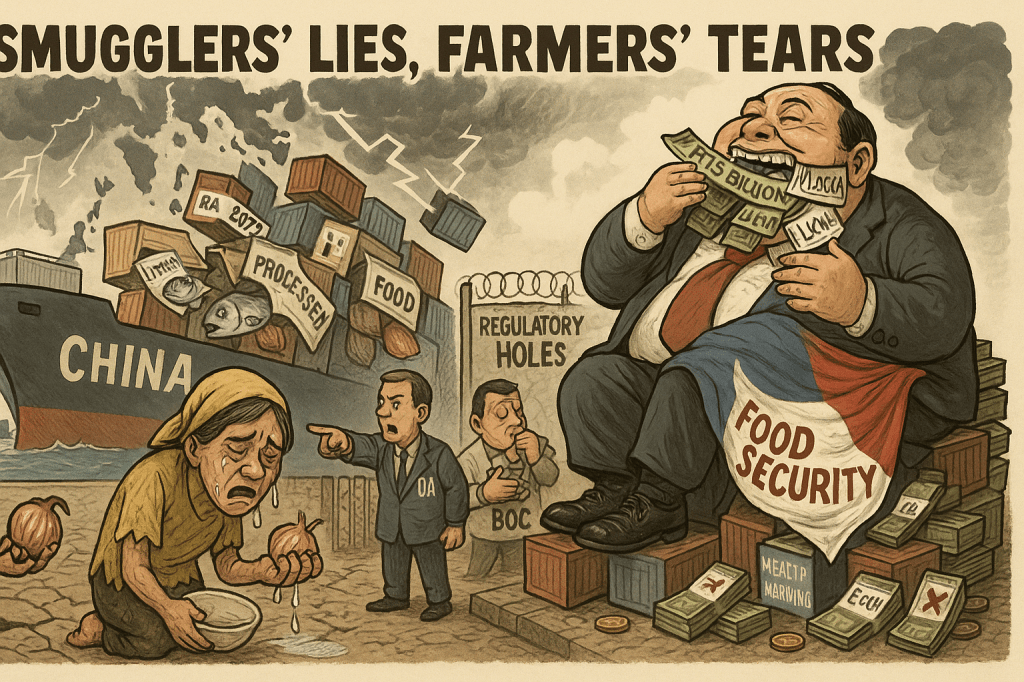

IN THE gray dawn at Subic Bay Freeport, 59 container vans lurk like thieves in the night, their contents masked by deceit. Labeled as “processed food,” they likely conceal fresh onions and fish smuggled from China to cheat Filipino farmers. This isn’t just fraud—it’s a gut punch to a nation’s food system, where profiteers gorge while the poor go hungry. The Department of Agriculture’s (DA) demand to halt these shipments, armed with the Anti-Agricultural Economic Sabotage Law (RA 12022), is a battle cry. But is it a lifeline for farmers or a hollow stunt? The truth lies in the rotten core of systemic failures, the crushing toll on rural lives, and the desperate need for reforms that go beyond impounding containers.

The Rotten Core: How Smugglers Exploit a Broken System

The smuggling crisis—evidenced by a P34 million onion and mackerel seizure at Manila Port—lays bare a system riddled with holes. Smugglers play a cunning game of regulatory arbitrage, misdeclaring fresh produce as processed food to dodge the DA’s Bureau of Plant Industry (BPI) and slip under the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) less stringent oversight. This trick thrives on fractured mandates: the DA spots violations, but only the Bureau of Customs (BOC), under the Department of Finance, can seize goods. Coordination gaps create a playground for corruption.

Corruption isn’t just a buzzword—it’s a shadow economy. The BOC’s chronic understaffing and outdated systems, despite the Customs Modernization and Tariff Act of 2016, invite bribes. Smugglers, often tied to shadowy firms like Latinx and Lexxa Consumer Goods, use shell companies to evade blacklisting, with 18 firms banned in 2025 alone. Yet new ones sprout like weeds, exploiting weak enforcement. The P15 billion in tax leakage over nine years isn’t just lost revenue—it’s stolen hope for rural schools, clinics, and farm aid.

China’s shadow looms large. Most smuggled goods originate there, reflecting a trade imbalance where the Philippines’ agricultural trade deficit hit US$5.9 billion in 2016. Cheap Chinese produce floods markets because local farmers, tethered to tiny 1-3 hectare plots and lagging productivity, can’t compete. Until these gaps are sealed, smuggling remains a lucrative hustle.

Crackdown or Charade: Is the DA Saving Farmers or Chasing Headlines?

The DA, led by Secretary Francisco Tiu Laurel Jr., casts its campaign as a shield for farmers and food safety. RA 12022 brands smuggling as economic sabotage, with life imprisonment and fines up to five times the goods’ value. The Manila Port seizure, where onions and mackerel were mislabeled as noodles and kimchi, shows the law’s bite. Laurel’s pledge to chase the “entire supply chain”—from consignees to brokers—aims to dismantle smuggling networks. A proposed China-specific risk assessment targets the biggest culprit.

But is this a genuine rescue or political theater? Blacklisting 18 firms in 2025 is a step, but smugglers’ knack for rebranding under new names suggests enforcement is a game of whack-a-mole. Critics argue the DA’s seizures sidestep root causes: high production costs, crumbling irrigation, and scarce post-harvest facilities that keep farmers like Juanita, a 54-year-old onion grower in Nueva Ecija, uncompetitive. Her crops rotted unsold in 2023 when smuggled onions crashed prices, yet the DA’s focus remains on ports, not fields.

Still, the DA’s defenders point to health risks. Smuggled onions at Manila Port tested positive for E. coli and salmonella, bypassing FDA checks. For the urban poor, reliant on cheap market produce, this is a hidden danger. The DA’s push aligns with President Marcos Jr.’s anti-smuggling directive, but its success depends on moving beyond photo-ops to structural change.

Hunger’s Price: How Smuggling Crushes the Poor

The crackdown’s fallout hits the marginalized hardest. Filipino farmers, 70% of whom live below the poverty line, lose when smuggled goods tank prices. In 2022-2023, onion price crashes left farmers like Juanita drowning in debt, some abandoning fields for urban slums. Yet halting shipments risks price spikes. Onions, a staple for low-income households, could turn unaffordable if supply tightens, as seen in past crackdowns. The poor, spending up to 50% of income on food, face a grim choice: pay more or risk tainted, smuggled goods.

The P15 billion tax leakage could fund programs like the P10-billion Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund, which boosts farmers with mechanization and seeds. But enforcement costs—inspections, legal battles—may eat up gains without systemic fixes. Meanwhile, smugglers behind firms like Latinx Consumer Goods pocket millions, their container vans a cruel contrast to the hand-to-mouth lives of rural families.

Customs’ Crossroads: Will the BOC Fight or Falter?

The BOC’s response to the DA’s demand will shape the crackdown’s fate. Full compliance—halting the 59 Subic shipments for inspection—would signal unity, as seen in the Manila Port joint operation. BOC Commissioner Bienvenido Rubio has called RA 12022 a “clear deterrent” (DOF statement), hinting at cooperation. Yet the BOC could dig in, citing its sole seizure authority under the CMTA. With only 3,000 customs personnel across 17 major ports, resource constraints may force a focus on trade over enforcement.

A likely path is joint inspections, as at Manila Port, where BOC, DA, and FDA exposed misdeclared goods. But without upgrades—more X-ray scanners, better training—the BOC risks being outsmarted. Resistance, even subtle, could deepen distrust, with 80% of Filipinos doubting anti-corruption efforts. The BOC’s choice will test whether it’s a partner in justice or a cog in a broken machine.

Breaking the Cycle: Bold Reforms to End the Smuggling Scourge

To stop this betrayal, the Philippines must pair enforcement with innovation and heart:

- Tech-Powered Accountability: Adopt blockchain to track imports, ensuring transparency from origin to port. AI-driven X-ray scanners, as used in Singapore, could detect misdeclared goods faster. Fund BOC’s tech upgrades with P2 billion annually to equip key ports.

- Farmer Empowerment: Expand P10-billion Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund to onion and fish producers. Implement price supports and cooperative-led processing plants to help farmers compete with imports.

- Smuggling Watchdog: Establish a DA-BOC-DOH task force with public scorecards on seizures and prosecutions, modeled on Thailand’s anti-smuggling units. Include whistleblower protections to expose corrupt officials.

- Trade Policy Reform: Simplify import rules to curb circumvention. Adopt tiered tariffs to protect local produce during harvest seasons while allowing imports during shortages.

- China Engagement: Pursue joint inspections with Chinese customs, as trialed in Vietnam, to curb smuggling at the source while preserving trade ties.

A Call to Arms: Justice for Farmers, Food for

All This isn’t just about onions in container vans; it’s about whether the Philippines will tolerate a food system where smugglers feast while farmers starve. The DA’s crackdown, backed by RA 12022, is a start, but it’s not enough. Without closing regulatory gaps, modernizing customs, and empowering farmers, seizures will remain a bandage on a broken system. For Juanita and millions like her, the fight against smuggling is a fight for dignity. The government must act—not with rhetoric, but with reforms that ensure every Filipino has a fair shot at a full plate.

Key Citations

- Anti-Agricultural Economic Sabotage Law (RA 12022)

- Manila Standard, 2025: DA to BOC: Suspend Release of Smuggled Farm Items

- Customs Modernization and Tariff Act (CMTA)

- 18 Firms Banned in 2025

- P15 Billion Tax Leakage Report

- Philippines Agricultural Trade Deficit

- inquirer, 2015:DA: Beware of contaminated smuggled onions

- Marcos Jr.’s Anti-Smuggling Directive

- 70% of Farmers Below Poverty Line

- Food Prices and the Poor

- Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund

- TV5, 2025: ‘LOSS OF TRUST’ | Over 80% of Filipinos want stronger system against corruption, says survey

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment