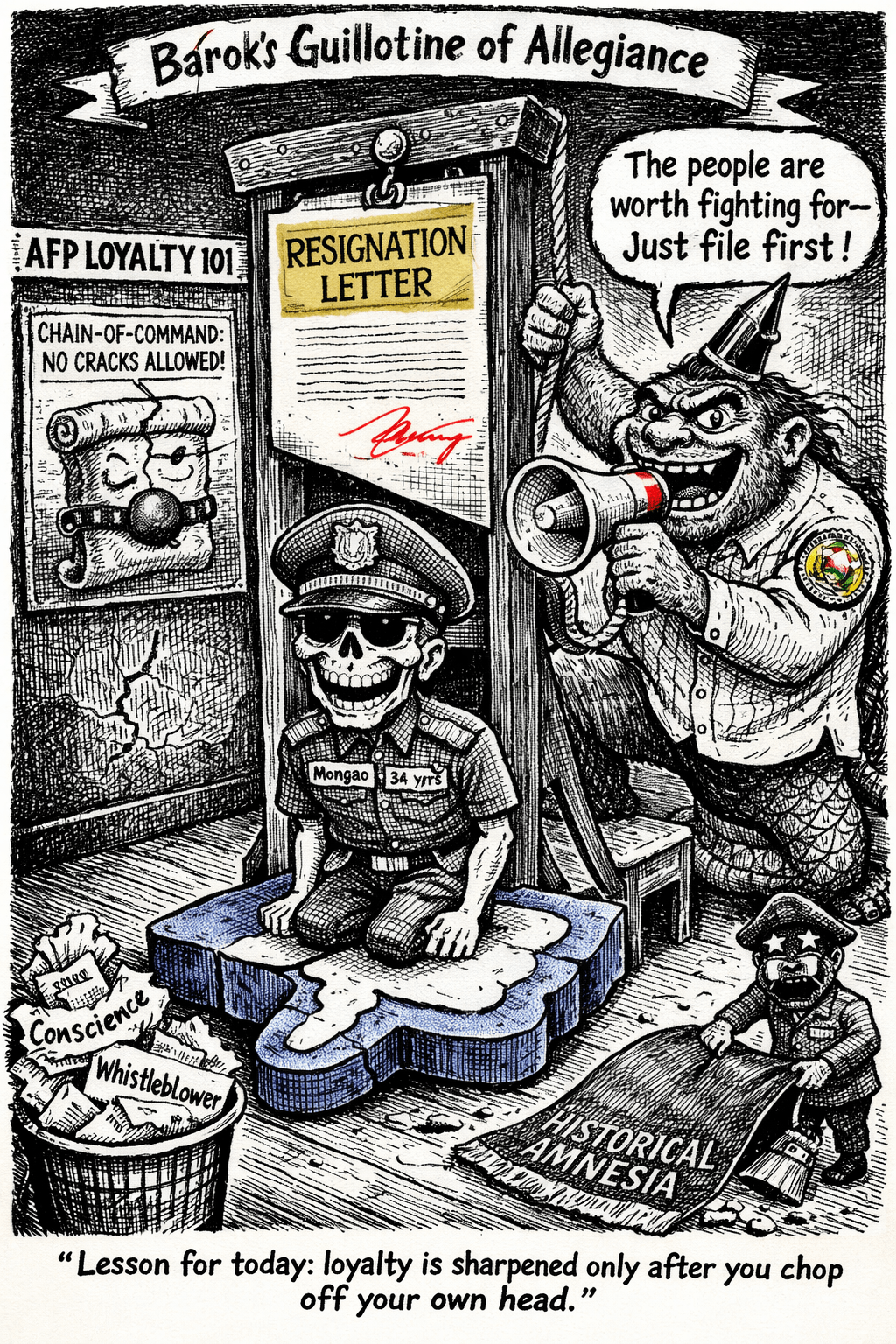

By Louis ‘Barok’ C Biraogo — July 22, 2025

SENATOR Francis “Kiko” Pangilinan’s Anti-Political Dynasty Bill, filed on July 9, 2025, is a fiery assault on the dynastic stranglehold choking Philippine democracy. Rooted in the 1987 Constitution’s mandate to ban political dynasties (Art. II, Sec. 26), it confronts a grim reality: 87% of governors, 80% of district representatives, and 53% of mayors hail from dynastic clans, with 4.5% of elective posts uncontested—a democratic decay rivaling autocratic regimes. Yet, with 70% of Congress entrenched in these very dynasties, the bill faces a brutal uphill battle.

This scathing critique rips apart the arguments, probes passage prospects, weighs impacts on the poor, and salutes Pangilinan’s audacious gambit, while proposing sharp strategies to slay the dynastic beast.

The Constitutional Ghost: Art. II, Sec. 26’s 38-Year Wait

The 1987 Constitution demands an end to political dynasties, yet Congress has shirked this duty for nearly four decades, a neglect as egregious as the environmental abandonment condemned in Oposa v. Factoran (224 SCRA 792).

Pangilinan’s bill bans relatives within the second degree of consanguinity or affinity from simultaneously holding or running for public office, aiming to honor this mandate. Proponents argue it enforces a self-executing constitutional intent (Manila Prince Hotel v. GSIS, 267 SCRA 408), as dynasties violate equal access to public service and public trust (Pamatong v. COMELEC, G.R. No. 161872, April 13, 2004).

PIDS data reveals the rot: 18 “obese dynasties” dominate, correlating with poverty and underdevelopment in the poorest provinces, per Querubin (2016).

Opponents counter that the bill’s second-degree scope is vague and overbroad, inviting a Chavez v. COMELEC (437 SCRA 415) smackdown for curbing candidacy rights. They claim dynasties plug governance gaps in a frail state, with clan networks—like Duterte’s “scholarship” schemes—delivering where bureaucracy fails. Cultural apologists lean on utang-na-loob, arguing dynasts are more accountable (Lande, 1965).

But these defenses crumble: nepotism flouts RA 6713, and the Supreme Court in Abbas v. COMELEC (G.R. No. 89651, Nov. 10, 1989) upheld the constitutionality of ARMM’s Organic Act and the region’s unique authority to pursue governance innovations, this can be seen as a legal foothold for imposing restrictions on political dynasties within autonomous regions—even absent a national enabling law. The bill’s logic is ironclad, but its breadth courts judicial peril.

Dynastic Math: Can a Congress of Clans Dismantle Its Own Power?

Passage is a pipe dream when 70% of Congress is dynastic—akin to “sharks voting to save the fish.” Past bills—SB 1765 (2018) and SB 264 (2019)—rotted in committee, crushed by self-interest.

COMELEC’s overstretched docket (COMELEC v. Estrella, 462 SCRA 124) risks implosion under citizen petitions, and “nuisance petitions” could paralyze elections (LDP v. COMELEC, 431 SCRA 502). Malacañang’s lukewarm stance—no urgency certification—dims hopes further.

Could a scandal rivaling Pharmally’s outrage force a vote? Perhaps, if public fury (e.g., 2025 Supreme Court petitions by Carpio et al.) and civil society (Makati Business Club, Movement Against Dynasties) converge. Even so, a diluted version (e.g., third-degree relatives) is more plausible than full passage.

Best case: 25% chance of bicameral approval with presidential push; likely outcome: death at second reading (<10% probability).

Poor vs. Patronage: Will Breaking Clans Break the Cycle of Poverty?

For the poor, the bill is a high-stakes gamble. Dynasties siphon Internal Revenue Allotment (IRA) funds, with the World Bank (2009) estimating 20% leakage to ghost projects in dynasty-dominated provinces.

Shattering this monopoly could funnel resources to health and education, boosting social mobility for non-dynastic candidates (teachers, NGO workers). ADB (2016) shows anti-dynasty reforms in India spiked foreign investment by 30%, a potential windfall for the Philippines.

But beware the fallout: dynastic patronage—scholarships, medical aid—often substitutes for a weak state, and its sudden loss could sting the poorest. “Shadow dynasties” (e.g., Estrada-Ejercito name-switching) or corporate elite capture (Poe-Llamanzares v. COMELEC, 682 SCRA 1) could emerge.

The bill bolsters institutions like the Ombudsman (Alzua v. Dee, 599 SCRA 496) but risks sidelining women candidates inheriting seats, demanding affirmative-action safeguards.

SC’s Dilemma: Enforce Oposa or Let Congress Off the Hook?

Congress’s 38-year inaction is a Marcos v. Manglapus-level constitutional betrayal (174 SCRA 245), defying Art. II, Sec. 26. Abbas greenlights tailored dynasty bans, but Chavez warns against overreach.

The bill’s citizen-petition mechanism, while Oposa-inspired, could swamp COMELEC. Ethically, RA 6713’s anti-nepotism stance clashes with utang-na-loob defenses, yet public office as a “birthright” is indefensible (CSC v. Peralta).

If Congress stonewalls, a People’s Initiative under RA 6735 could force the issue, though Santiago v. COMELEC (270 SCRA 106) deems the law inadequate, daring the Supreme Court to intervene.

Pangilinan’s Quixotic Gambit

Pangilinan’s crusade is a Manila Prince Hotel-style stand for constitutional fidelity—heroic, if quixotic. His empirical rigor, wielding PCIJ’s “obese dynasties” data, and moral thunder (“public office not a birthright”) expose dynastic rot.

In a Congress of clans, his bill is a middle finger to a system that laughs at equal access. If “democracy” means uncontested seats and family fiefdoms, why not let the Supreme Court crown mayors?

Battle Plan: Surgical Strikes to Topple Dynastic Fortresses

To outmaneuver dynastic defenses, Pangilinan must wield precision:

- Tighten the Noose: Restrict bans to first-degree relatives initially, dodging Chavez-style overbreadth attacks while testing enforcement.

- Unleash the Ombudsman: Shift petition adjudication to the Ombudsman, easing COMELEC’s burden and leveraging Alzua’s accountability framework.

- Fund the Underdogs: Subsidize non-dynastic candidates, fulfilling Art. II, Sec. 26’s equal-access promise.

- Phase the Revolution: Roll out bans incrementally (barangay 2028, municipal 2031, provincial 2034) to minimize chaos.

- Go Nuclear: Launch a People’s Initiative under RA 6735, forcing the Supreme Court to revisit Santiago and confront Congress’s betrayal.

Verdict: Republic or Clan Cartel?

Pangilinan’s bill is a constitutional clarion call, ethically unassailable, and empirically urgent, yet it’s shackled by a Congress of dynasts who profit from the status quo. Without surgical tweaks or a cataclysmic scandal, it risks joining its predecessors in legislative limbo.

The Philippines faces a stark choice: a republic where leadership is earned or a cartel where power is inherited. Pangilinan’s gambit demands not just legislative courage but judicial and public resolve to reclaim democracy from dynastic clutches.

Key Citations

- 1987 Constitution of the Philippines: Art. II, Sec. 26; Art. III, Secs. 1, 4; Art. X, Sec. 17; Art. XI, Sec. 1.

- Manila Prince Hotel v. GSIS, 267 SCRA 408 (1997): On self-executing constitutional provisions.

- Oposa v. Factoran, 224 SCRA 792 (1993): On legislative dereliction of constitutional duties.

- Abbas v. COMELEC (G.R. No. 89651, Nov. 10, 1989) – Implicitly affirmed the legislature’s authority to include mechanisms for addressing political inequality—which may include political dynasty restrictions.

- Chavez v. COMELEC, 437 SCRA 415 (2004): On candidacy restrictions.

- Pamatong v. COMELEC (G.R. No. 161872, April 13, 2004): Public office not a property right.

- Alzua v. Dee, 599 SCRA 496 (2009): On Ombudsman’s role in accountability.

- Santiago v. COMELEC, 270 SCRA 106 (1997): On inadequacy of RA 6735.

- COMELEC v. Estrella, 462 SCRA 124 (2005): On COMELEC’s docket constraints.

- LDP v. COMELEC, 431 SCRA 502 (2004): On nuisance petitions.

- Poe-Llamanzares v. COMELEC, 682 SCRA 1 (2016): On alternative elite influence.

- RA 6713 (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards): Anti-nepotism provisions.

- RA 6735 (Initiative and Referendum Act): People’s Initiative framework.

- PCIJ Data on Political Dynasties: Statistics on dynastic dominance.

- World Bank (2019): On IRA leakage in dynasty-controlled provinces.

- Mendoza, Ronald U., et al. Political Dynasties and Human Development Investments: Evidence of Linkages and Impacts from the Philippines. Ateneo School of Government, 2016,

- ADB (2016): On anti-dynasty reforms and investment.

- Senate Bill 1765 (2018) (PDF): Previous anti-dynasty attempt.

- Senate Bill 264 (2019) (PDF): Previous anti-dynasty attempt.

- Querubin (2016): Academic study on dynasties and poverty.

- Lande, Carl H. Leaders, Factions, and Parties: The Structure of Philippine Politics. Southeast Asian Studies, Yale University, 1965. – On Filipino political culture and utang-na-loob.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

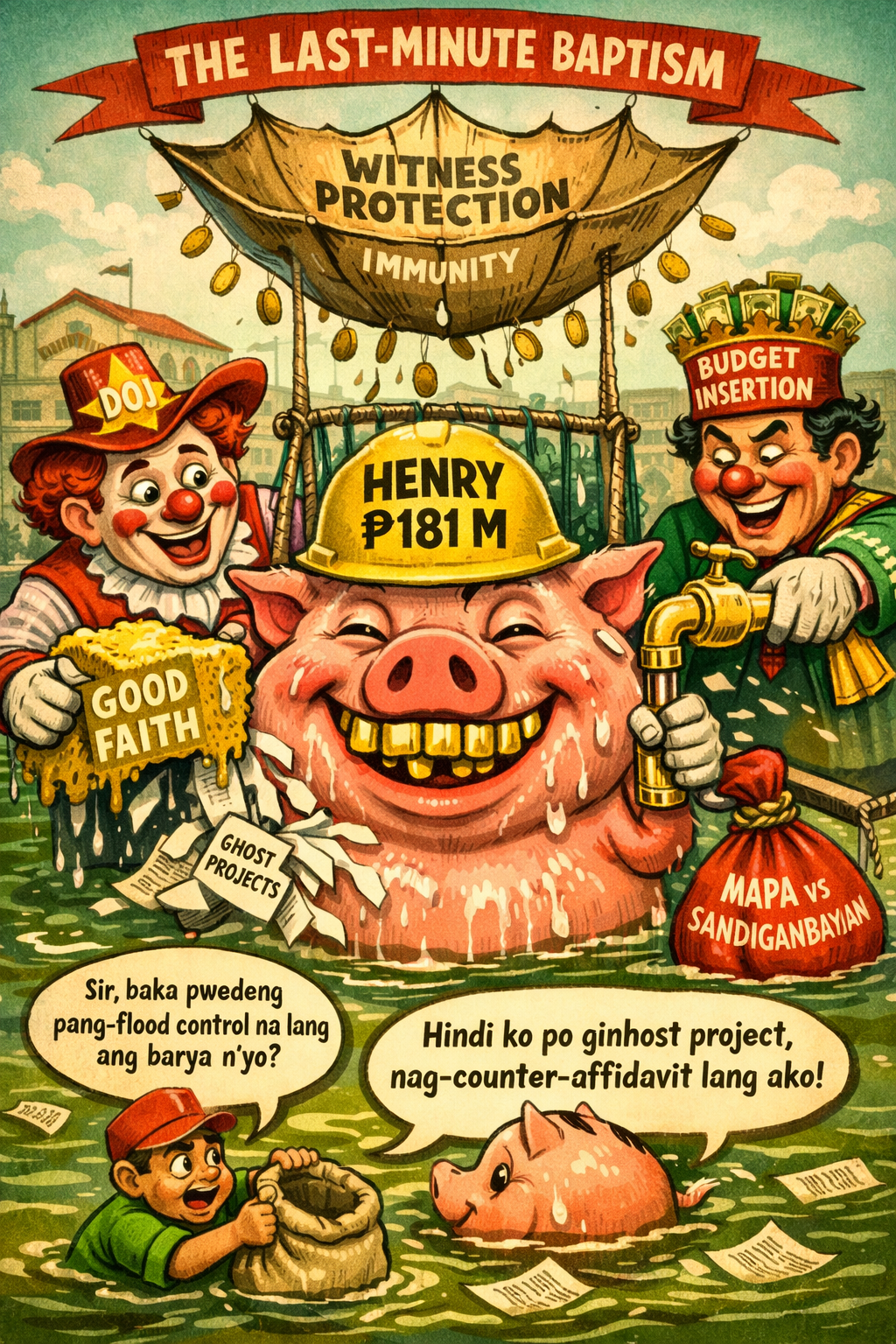

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

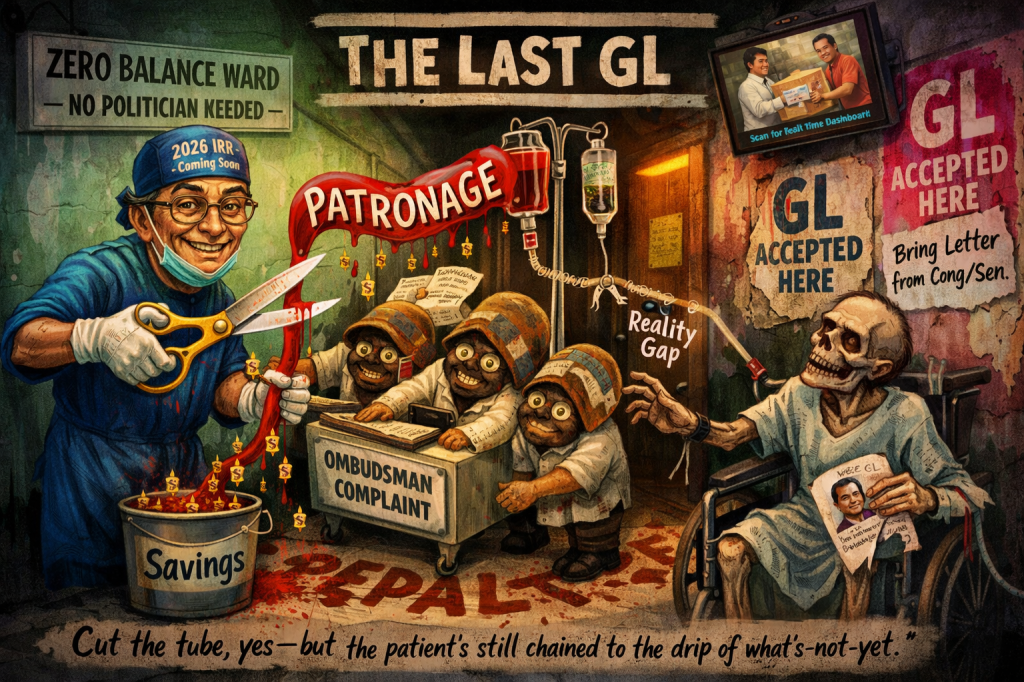

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

- “Allocables”: The New Face of Pork, Thicker Than a Politician’s Hide

- “Ako ’To, Ading—Pass the Shabu and the DNA Kit”

Leave a comment