By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — July 26, 2025

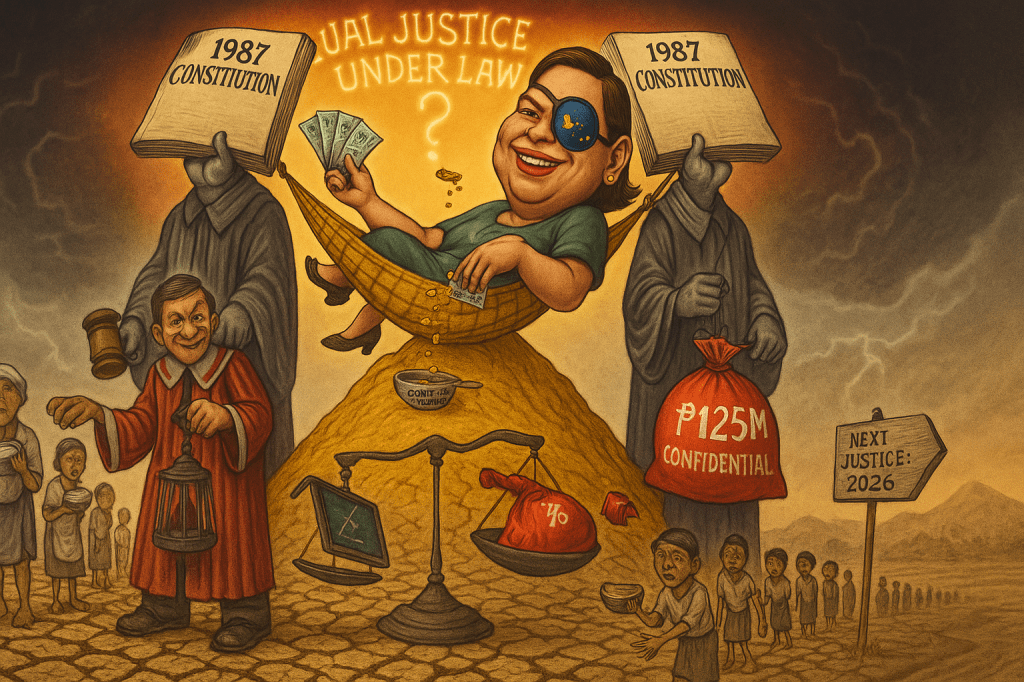

ON July 25, 2025, the Philippine Supreme Court, with the finesse of a chess grandmaster and the nerve of a high-wire acrobat, obliterated the impeachment articles against Vice President Sara Duterte. Invoking the 1987 Constitution’s one-year rule and a bold new arsenal of due process demands, the Court slammed the brakes on a politically explosive process. Was this a principled stand for constitutional purity or a masterclass in shielding a powerful ally? This scorching critique rips apart the Court’s legal reasoning, unmasks the political machinations, and exposes the gut-punch to the poor, all while spotlighting the ethical quagmire threatening the Court’s legitimacy.

The One-Year Rule: Constitutional Dodge or Ironclad Shield?

The Court anchored its ruling on Article XI, Section 3(5) of the 1987 Constitution: “No impeachment proceedings shall be initiated against the same official more than once within a period of one year.” The logic appears airtight—three citizen-initiated complaints filed in December 2024 were “initiated” upon filing and referral to the House Committee on Justice, as defined in Francisco Jr. v. House (2003). When the House archived these and endorsed a fourth, House-initiated complaint on February 5, 2025, the Court declared it a violation of the one-year bar, pegging the clock to the first filing.

But this is a constitutional sleight of hand. Francisco Jr. clarified “initiation” for citizen complaints under Section 3(2), which require Committee referral. In contrast, a House-initiated complaint under Section 3(4), backed by one-third of lawmakers, skips the Committee and rockets to the Senate. The Court’s conflation of these distinct mechanisms ignores their textual and procedural divergence.

In Gutierrez v. House (2011), the Court allowed two complaints filed within a year to proceed as a single “proceeding” because they were referred simultaneously. Here, the Court’s dogmatic stance—that archived complaints trigger the bar—creates a loophole where a single frivolous filing could grant an official a year-long immunity shield. This isn’t fidelity to the Constitution; it’s a judicial barricade against accountability.

Due Process Charade: Rewriting Impeachment’s Playbook

The Court’s second strike was a dazzling display of due process theater: mandating evidence disclosure to all House members, a sufficiency standard for evidence, and a pre-transmittal hearing for the respondent. These requirements, cloaked in the rhetoric of fairness, sound righteous but collapse under scrutiny.

Impeachment, as Francisco Jr. emphasized, is a political process, not a judicial trial. The Constitution vests the House with sole initiation power (Art. XI, Sec. 3(1)), and House Rules allow the respondent to answer only after Committee referral, not before a plenary vote. By imposing courtroom-style due process, the Court hijacked the script, turning a political battlefield into a judicial stage.

Contrast this with Gutierrez, where the Court upheld the House’s discretion to expedite proceedings without such procedural shackles. The justices’ insistence on pre-transmittal hearings and universal evidence access—absent from the Constitution or House Rules—reeks of overreach. It’s as if the Court, with its crystal-clear hindsight vision, decided Congress can’t be trusted to wield its own constitutional sword. This isn’t protecting fairness; it’s judicial meddling masquerading as principle.

Political Puppetry: A Judicial Lifeline for a Duterte Dynasty?

The ruling’s timing and context scream political favoritism. Sara Duterte, scion of the Duterte dynasty, stands at the epicenter of a bitter Marcos-Duterte feud. The impeachment complaints, fueled by allegations of ₱125 million in misused confidential funds, erupted amid this power struggle.

Compare this to the 2012 impeachment of Chief Justice Renato Corona, which sailed through without such judicial barricades. Corona’s trial, though politically charged, proceeded because the Court respected Congress’ domain. Here, the justices seem to have crafted a bespoke shield for Duterte, halting a process that threatened a political juggernaut.

This isn’t just a House vs. Court skirmish—it’s full-blown institutional warfare. By nullifying the articles, the Court didn’t merely clip Congress’ wings; it gutted its constitutional authority to initiate impeachment. The Senate, robbed of jurisdiction, is left twiddling its thumbs. If Francisco Jr. cautioned against judicial overreach into political questions, this ruling tosses that warning into the shredder, tilting the balance of power toward the judiciary. The message is unmistakable: The Court, not Congress, calls the shots on impeachment.

Robbing the Poor: Confidential Funds Stolen, Justice Deferred

At the core of the complaints lies the ₱125 million confidential funds scandal—alleged undocumented disbursements, including ₱50,000 monthly “cash gifts,” violating RA 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act) and COA Circular No. 2012-003 (PDF). The human toll is staggering: ₱125 million could fund 25 rural classrooms (at ₱5 million each, per DepEd estimates) or 1,250 cataract surgeries (at ₱100,000 each, per DOH data). For the poor, this isn’t just numbers—it’s the difference between a child’s education, a parent’s sight, or despair.

Yet, the Court’s ruling delays accountability until February 2026, nearly the end of Duterte’s term. Compare this to the glacial justice system for ordinary Filipinos. Ombudsman v. Reyes (2021) exposed average delays of 3–5 years in criminal cases, with indigent defendants rotting in overcrowded jails. The Court’s lightning-fast resolution here—months, not years—lays bare a brutal disparity. The poor endure endless waits for justice; the powerful get a constitutional get-out-of-jail-free card.

Ethical Quicksand: Double Standards and a Crisis of Trust

The Court’s procedural obsession here stands in stark contrast to its leniency in Duterte v. Senate (2024), where it upheld broad legislative inquiry powers despite due process concerns. In that case, the Court deferred to Congress’ autonomy, citing the political nature of inquiries. Why the sudden procedural puritanism now?

This flip-flop fuels accusations of double standards, suggesting the Court bends its principles to protect the elite. Public trust, already on life support, takes a beating. SWS surveys from 2024 reveal 65% of Filipinos see corruption as pervasive. A ruling perceived as shielding Duterte risks plunging trust further into the abyss, especially among the poor, who watch resources meant for them vanish into the ether. When the Court prioritizes technicalities over transparency, it erodes its own moral foundation.

The Final Reckoning: A Court Unmoored?

The Supreme Court saved Sara Duterte from impeachment—but at what cost to its own legitimacy? By brandishing the one-year rule and conjuring due process mandates, it may have upheld constitutional text but betrayed its spirit. The ruling stalls justice for alleged graft, castrates Congress’ authority, and widens the gulf between the powerful and the powerless.

In its zealous defense of procedure, the Court risks becoming a willing architect of impunity. The question burns: Can a judiciary that shields the elite still claim to serve the nation?

Key Citations:

- 1987 Constitution, Art. XI, Secs. 2–5.

- Francisco Jr. v. House, G.R. No. 160261 (2003).

- Gutierrez v. House, G.R. No. 193459 (2011).

- RA 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act).

- COA Circular No. 2012-003.

- Ombudsman v. Reyes, G.R. No. 234135 (2021).

- Duterte v. Senate, G.R. No. 256789 (2024).

- GMA Integrated News, “SC declares Articles of Impeachment vs. Sara Duterte unconstitutional,” July 25, 2025.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment