By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — July 28, 2028

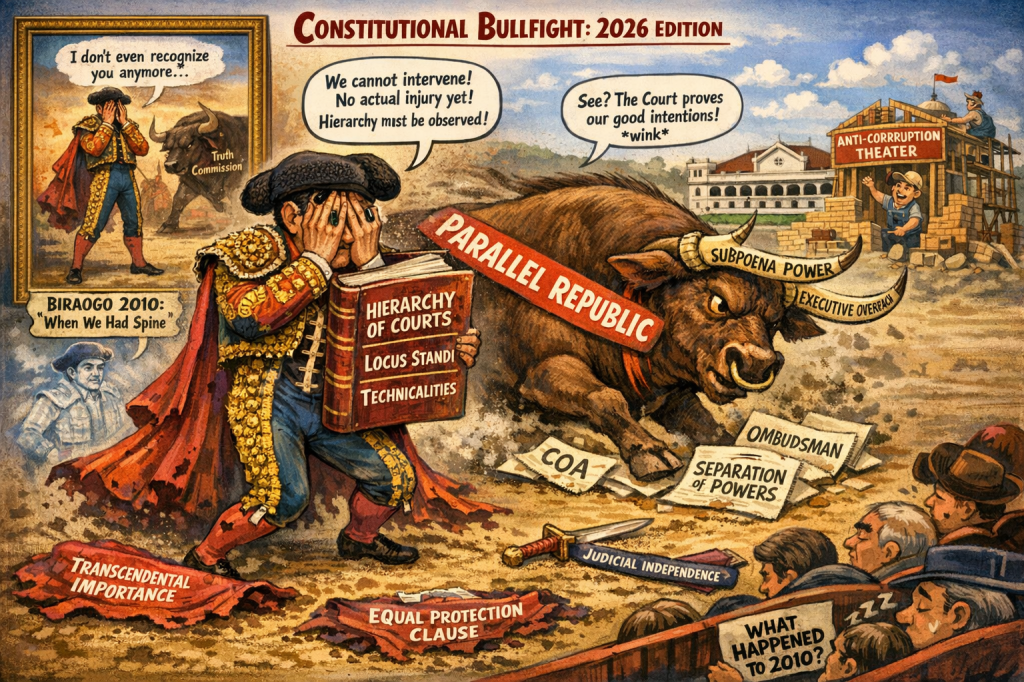

THE Supreme Court didn’t just rewrite the rules on impeachment—it handed Congress a constitutional grenade with the pin already pulled.

On July 25, 2025, the Philippine Supreme Court unanimously voided the impeachment complaint against Vice President Sara Duterte, citing violations of the Constitution’s one-year bar and due process requirements. This isn’t just a legal slap on the wrist for the House of Representatives; it’s a seismic shift in the balance of power, one that could shield future corrupt officials behind a fortress of procedural technicalities.

With accusations of graft, misuse of P600 million in confidential funds, and assassination threats hanging over Duterte, the ruling doesn’t just save her—it sends a chilling message: steal big, threaten bigger, and let the Court’s nitpicking save you.

The One-Year Bar: A Loophole Big Enough to Drive a P600M Confidential Fund Through

The Court’s 97-page decision, penned by Senior Associate Justice Marvic Leonen, hinges on a radical redefinition of what it means to “initiate” an impeachment complaint. Let’s rewind to Francisco v. House of Representatives (2003), where the Court clearly stated that an impeachment complaint is initiated only when referred to the House Committee on Justice.

Fast forward to 2025, and the justices seem to have hopped into a time machine, retroactively declaring that complaints merely filed and archived—never referred—count as “initiated” and “effectively dismissed” once Congress adjourns. Former Justice Adolf Azcuna called this “legally correct but rather unfair,” and he’s being polite.

Did the Court just punish the House for following a 22-year-old precedent it had no reason to doubt?

- Retroactive Punishment: The House, backed by over one-third of its members, sent a fourth complaint to the Senate, only to have the Court pull the rug out with a new rule applied retroactively.

- Constitutional Loophole: The one-year bar, meant to prevent harassment via serial complaints, has been weaponized into a shield for the powerful. The first three complaints against Duterte—filed in December 2024—were never referred to committee, yet the Court deemed them sufficient to trigger the bar, blocking the fourth complaint filed in February 2025.

The National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL) shredded this logic, arguing that unreferred complaints are constitutionally invisible, lacking the formal initiation required by Francisco. By treating these as “initiated,” the Court has created a loophole where officials can dodge accountability simply because earlier, unacted-upon complaints clogged the pipeline.

The clock is ticking—not for Duterte, but for Philippine democracy.

Due Process Theater: The House Isn’t a Courtroom

The Court’s insistence on “furnish-and-respond” requirements is equally baffling. The justices faulted the House for not providing Duterte with the articles of impeachment or a chance to respond before sending the case to the Senate.

Since when does the House—a political body—owe respondents Miranda rights before impeachment?

The Constitution’s Article XI, Section 3(4) is crystal clear: a complaint backed by one-third of the House automatically becomes the articles of impeachment, no pre-trial pleasantries required. The NUPL rightly points out that due process kicks in at the Senate trial, where the respondent can mount a defense.

By imposing courtroom-like standards on a political process, the Court is playing dress-up as Congress’s impeachment committee—with lifetime tenure to boot.

- Judicial Overreach: UP law professor Paolo Tamase noted that these new guidelines could benefit impeachable officials, including the justices themselves, by bogging down the process with red tape.

- Procedural Absurdity: Requiring the House to act like a court before the Senate gets the case is like demanding a grand jury hold a full trial before issuing an indictment.

Congratulations, SCOTP! You’ve made impeachment harder to file than a Mars colonization lawsuit.

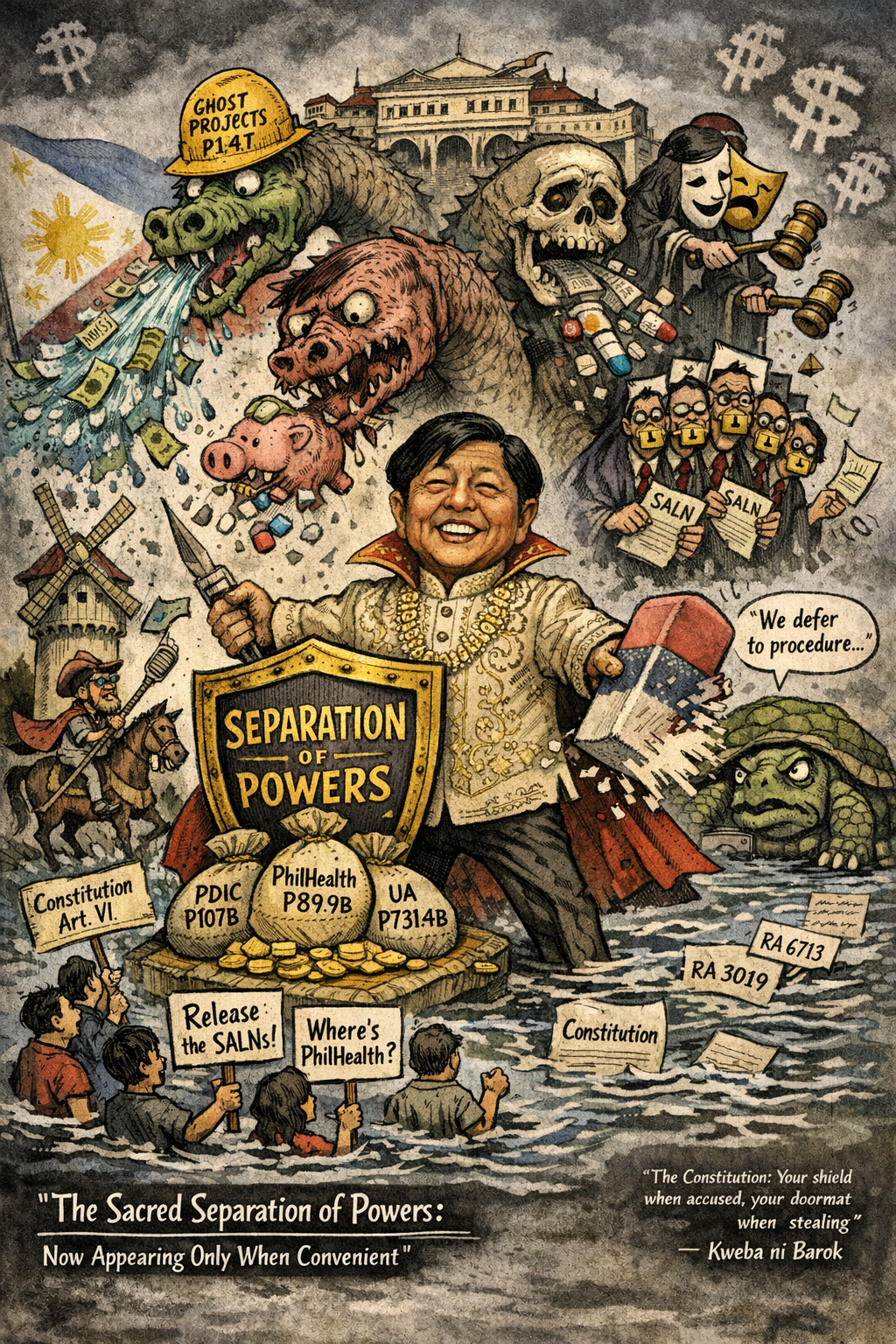

Separation of Powers Suicide: The Court as Congress’s Babysitter

Retired Justice Antonio Carpio didn’t mince words: impeachment is a “clearly political process,” and the Court’s meddling risks “distorting the constitutional scheme.” He’s right.

The Constitution grants the House the sole power to initiate impeachment, yet the Court’s ruling imposes new procedural hurdles not found in the text. By redefining “initiation” and demanding pre-transmission due process, the justices have effectively turned themselves into the gatekeepers of a process meant to be Congress’s domain.

- Rushed Judgment: Former Chief Justice Artemio Panganiban urged respect for the ruling but questioned its haste, suggesting oral arguments could have clarified this “monumental case.”

- Legislative Sleaze vs. Judicial Overreach: Justice Ramon Paul Hernando’s concurrence exposes the House’s “immoral maneuvers”—secret caucuses, withheld agendas—but does judicial overreach cure legislative sleaze, or just compound the stench?

By policing the House’s internal processes, the Court risks undermining the separation of powers it claims to protect. As Carpio warned, this sets a precedent where courts can micromanage Congress, eroding the checks and balances the Constitution envisions.

The irony? The Court’s activism may provoke Congress to retaliate—think defunding judicial perks or packing the Court with loyalists. The justices may have won this round, but they’ve lit a fuse for future institutional chaos.

The Bloodstains: Political Fallout and a Rigged 2028 Race

The political consequences of this ruling are as explosive as Duterte’s alleged assassination threats. The complaint wasn’t just about procedural niceties—it targeted her alleged misuse of over P600 million in confidential funds, including P125 million spent in a mere 11 days, and her chilling threat to kill President Marcos, the First Lady, and Speaker Romualdez if a supposed plot against her succeeded.

The Court’s ruling doesn’t just delay accountability until February 2026; it hands Duterte a get-out-of-jail-free card, preserving her eligibility for the 2028 presidential race.

This isn’t jurisprudence—it’s political engineering.

- Congressional Retaliation: The House, stung by the Court’s rebuke, is mulling a motion for reconsideration, but the damage is done. Expect legislative pushback—perhaps slashing judicial budgets or pushing constitutional amendments to reclaim impeachment powers.

- Senate’s Dilemma: Senator Risa Hontiveros warned that the ruling “sets a dangerous precedent,” potentially hobbling future accountability efforts. The Senate now faces a choice: proceed with a trial and risk contempt, or bow to the Court and signal that impeachment is a judicial plaything.

- 2028 Wildcard: By keeping Duterte in the game, the ruling deepens the Marcos-Duterte rift, fueling a political tinderbox that could ignite before the next election.

The Rule of Law Autopsy: A Precedent Corpse and a Trust Deficit

The Court didn’t just void Duterte’s impeachment; it buried Francisco v. House without so much as a eulogy. The victims? Stare decisis and legislative trust.

By retroactively redefining “initiation,” the Court undermined the predictability that the rule of law demands. Future Congresses now face a minefield of conflicting precedents, where every impeachment risks a judicial veto.

Public trust, already battered by perceptions of a Duterte-friendly Court (13 of 15 justices were appointed by her father), takes another hit. As Senator Francis Pangilinan noted, this ruling could let justices “interfere with their own impeachment trials,” a conflict of interest wrapped in constitutional robes.

Internationally, the ruling makes the Philippines look like a judicial backwater. In the U.S., even Donald Trump got his Senate trial, messy as it was. Here? The Court delivered a technical KO before Round 1, leaving accountability in the dust.

The Philippines’ impeachment process, once a robust check on power, now risks becoming a procedural quagmire where the powerful can hide behind the Court’s skirts.

The Dissent We Wish Existed

A razor-sharp, phantom dissenter would write:

“Justice Leonen’s opinion reads like a legislative manual, not a constitutional mandate. The Constitution demands accountability over technicalities. By redefining ‘initiation’ and imposing courtroom rules on a political process, the Court has not protected due process—it has crippled the House’s power to check high officials. The one-year bar was meant to prevent harassment, not to shield graft and threats. This ruling doesn’t uphold the Constitution; it rewrites it to favor the powerful.”

Such a dissent would have reminded us that the Constitution’s spirit—accountability, not obstruction—should guide the Court, not procedural pedantry.

The Verdict: A Constitutional Coup in Robes

The Supreme Court’s ruling is a masterclass in judicial jujitsu, flipping a political safeguard into a weapon for the powerful. By redefining “initiation,” imposing extra-constitutional hurdles, and shielding Duterte from accountability, the Court has recalibrated the separation of powers—tilting it toward itself.

The stakes couldn’t be higher: a weakened Congress, a politicized judiciary, and a public left wondering if the rule of law is just a game for the well-connected.

The House may fight back, the Senate may push forward, but one thing is clear: this isn’t just a ruling—it’s a constitutional coup by robe-wearing tacticians.

The clock is ticking, and the next move will decide whether Philippine democracy can still hold the powerful to account.

Key Citations

- Francisco v. House of Representatives (2003): Established that an impeachment complaint is initiated only upon referral to the House Committee on Justice.

- 1987 Philippine Constitution, Article XI, Section 3(4): Specifies that a complaint backed by one-third of the House automatically becomes articles of impeachment.

- Rappler, July 27, 2025: Sara impeachment: What are implications of SC’s new ruling? – Azcuna’s statement, NUPL’s arguments, and Tamase’s critique of due process guidelines.

- The Manila Times, July 22, 2025: House to Court: Impeachment legal – House’s defense of its impeachment timeline.

- Philstar.com, July 25, 2025: VP Sara Duterte’s trial must go on — senators – Senator Hontiveros’s warning on the ruling’s precedent.

- PhilNews, July 26, 2025: House on SC Decision over Sara Duterte Impeachment Articles: “Our constitutional duty to uphold truth and accountability does not end here” – Duterte’s legal team and House spokesperson’s statements.

- GMA News Online, July 25, 2025: Senators split on SC decision vs. Sara Duterte impeachment – Senators’ reactions to the ruling.

- BBC, July 25, 2025: Philippines top court blocks impeachment bid against Sara Duterte – Political implications for the 2028 presidential race.

Disclaimer: This is legal jazz, not gospel. It’s all about interpretation, not absolutes. So, listen closely, but don’t take it as the final word.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment