By Louis ‘Barok’ C Biraogo — August 3, 2025

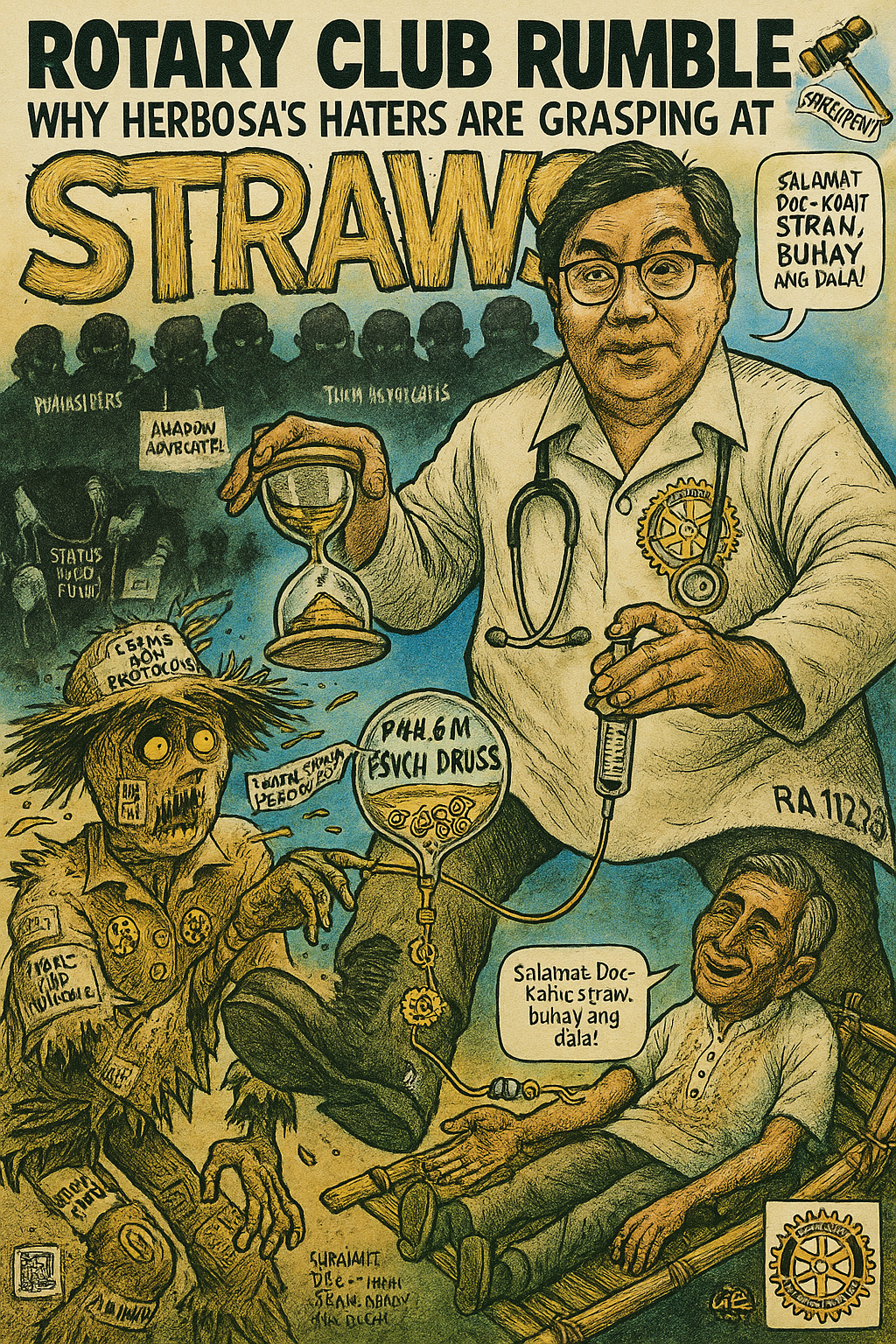

THEY don’t want you to know about the Great Psychiatric Drug Scandal of 2024, but I’m about to blow this wide open. While you were distracted by celebrity gossip and traffic complaints, a shadow cabal of vindictive pen-pushers orchestrated the perfect takedown of Health Secretary Ted Herbosa. His crime? The audacity to believe sick Filipinos deserved medication more than bureaucrats deserved their sacred paperwork rituals. The evidence is all there: ₱44.6 million in psychiatric drugs, delivered efficiently to the Rotary Club of Quezon City for distribution. But here’s what the Ombudsman doesn’t want you to realize—this isn’t about graft, it’s about power. They’re sending a message to every reformist who dares suggest that maybe, just maybe, we shouldn’t let people suffer while administrators play their little sovereignty games.

I. The Opening Salvo: A Scandal Built on Lies

Imagine a Health Secretary racing against time to save ₱44.6 million in psychiatric drugs from expiring in a warehouse while mental health patients beg for care. His bold move? Partner with the Rotary Club, a global humanitarian titan, to get those drugs to the underserved. His punishment? A fusillade of Ombudsman complaints from disgruntled DOH employees and shadowy “health advocates” crying graft, misconduct, and procedural heresy. This isn’t just an attack on Herbosa—it’s a warning to every public servant who dares disrupt the status quo.

The stakes are sky-high: Herbosa faces dismissal, criminal charges, and a trashed reputation. But this case is weaker than a wet tissue. What follows is a ruthless legal takedown, a parade of precedents proving Herbosa’s innocence, and a demand to squash this farce before it wastes another peso of taxpayer money.

II. Legal Armageddon: Obliterating the Allegations

The complainants—DOH insiders and unnamed “advocates”—throw a laundry list of charges: violations of Republic Act No. 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act), RA 9711 (Food and Drug Administration Act), RA 10918 (Philippine Pharmacy Act), and RA 6713 (Code of Conduct for Public Officials). They claim Herbosa funneled drugs to an unlicensed Rotary Club, dodging protocols and endangering public health. Sounds juicy, right? Too bad it’s a legal house of cards. Let’s burn it down.

A. Unassailable Legal Fortress

1. Herbosa’s Ironclad Authority

Republic Act No. 11223, the Universal Health Care Act, hands the Health Secretary sweeping powers to ensure equitable health access. Section 5 tasks the DOH with formulating national health policy and allocating resources to serve the underserved—exactly what Herbosa did by tapping the Rotary Club for a medical mission. The law doesn’t chain him to bureaucratic minutiae; it demands results.

The Supreme Court agrees. In Pharmaceutical and Health Care Association v. Duque (G.R. No. 173034, 2007), the Court upheld the Health Secretary’s expansive discretion in public health matters, as long as statutory boundaries aren’t crossed. The complainants can’t cite a single provision in RA 11223 or the Administrative Code of 1987 (EO No. 292) that Herbosa violated. Their “misconduct” claims are legal vaporware.

2. Emergency Powers Unleashed

The Administrative Code (Book IV, Title VIII, Chapter 3) empowers the DOH to act decisively in health crises, including resource reallocation to prevent waste. Near-expiry drugs gathering dust while mental health patients suffer? That’s an emergency Herbosa was obligated to tackle. In Nepomuceno v. Duterte (UDK No. 16838, 2020), the Supreme Court greenlit deviations from protocol in emergencies, provided they’re reasonable and documented. Herbosa’s move to the Rotary Club checks both boxes.

3. Swatting Away Irrelevant Precedents

The complainants might clutch DOH v. Phil Pharmawealth (G.R. No. 182358, 2008), where the Court upheld DOH procurement rules. But that case dealt with a private contractor’s bidding failures, not a Secretary’s humanitarian allocation. It’s irrelevant. Similarly, Nepomuceno involved unapproved vaccines, not FDA-compliant, DOH-procured drugs like Herbosa’s. These cases are legal red herrings.

Quotable Soundbite:

“Herbosa didn’t just follow the law—he rewrote the playbook for saving lives. The Ombudsman should probe the complainers’ vendettas, not his victories.”

III. Procedural Bloodbath: Exposing the Complainants’ Shoddy Case

The Ombudsman complaints are a procedural trainwreck. Let’s rip them apart and expose their fatal flaws.

A. Questionable Accusers, Ulterior Motives

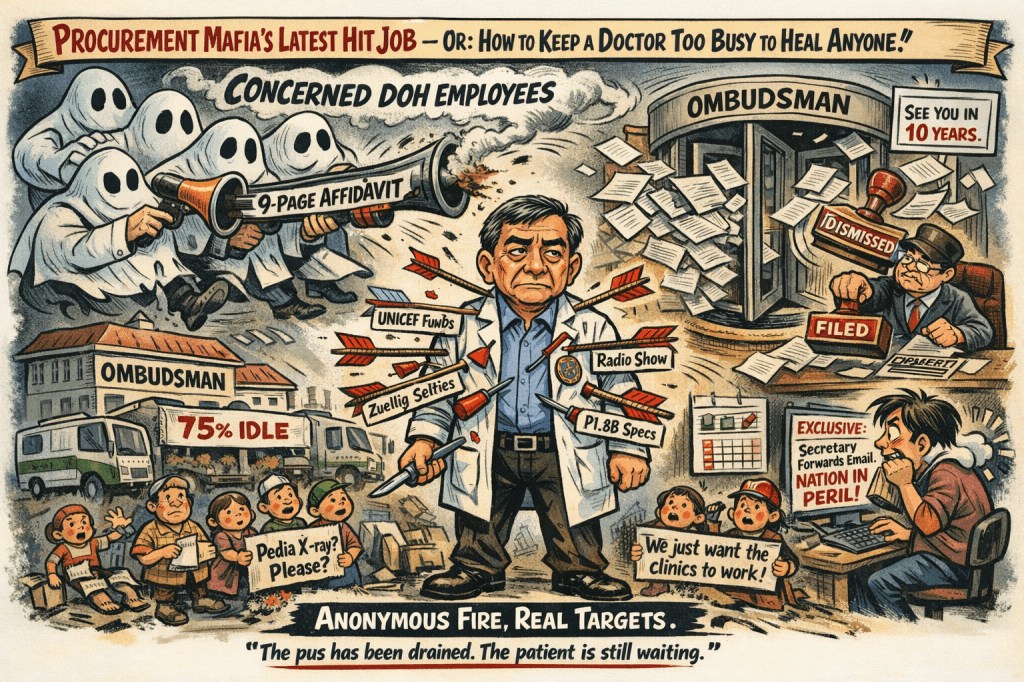

Motives? Pure poison. Herbosa’s reforms—streamlining procurement, boosting mental health—have ruffled feathers in a DOH rife with cronyism. This screams “Witch Hunt Narrative.” Reformers like Herbosa always draw fire from entrenched interests. The Ombudsman should demand the complainants’ affiliations under RA 6770, Section 12—bet they’re hiding ties to rival groups or spurned suppliers.

Who are these complainers? Anonymous DOH employees and “health advocates” with zero transparency. Under the Ombudsman Act (RA 6770, Section 12), the Ombudsman can accept complaints from any person, no direct injury required, thanks to its broad mandate as a public watchdog. But that doesn’t mean these accusers get a free pass. Their anonymity screams ulterior motives. Are they disgruntled staff sidelined by Herbosa’s reforms? Advocates tied to rival groups or spurned suppliers? The Ombudsman should demand disclosure of their affiliations under RA 6770, Section 12—bet they’re hiding something juicy. This reeks of the “Witch Hunt Narrative”: reformers like Herbosa always draw fire from bureaucrats guarding their fiefdoms.

B. Complaints Riddled with Holes

The Ombudsman’s Rules of Procedure (AO No. 07, Rule II) require complaints to include affidavits and hard evidence. The Manila Times report cites none—just buzzwords like “misconduct” and “mismanagement.” No inventory logs proving concealment. No emails showing corrupt intent. It’s a legal ghost story, all smoke and no fire.

C. Evidence? What Evidence?

RA 3019, Section 3(e) demands proof of manifest partiality, bad faith, or gross negligence causing injury or unwarranted benefits. The complainants have nada—no evidence Herbosa pocketed a peso or acted maliciously. The drugs went to a globally respected non-profit, not a cartel. RA 9711 and RA 10918 violations require proof of unsafe distribution or adulteration—again, zero evidence. This case is DOA.

D. Herbosa’s Protocol Compliance

Department Order No. 2025-0080, per the Manila Times, shows Herbosa followed DOH sub-allotment processes, with approvals from Undersecretary Bravo and Supply Chain officers. If these documents hold, they’re a knockout punch. The Ombudsman’s own precedent, like Ona v. Ombudsman (2014), tossed similar charges when officials showed internal compliance, even with imperfect paperwork.

Quotable Soundbite:

“The complainants are tossing legal spaghetti at the wall, praying it sticks. Herbosa’s only sin was refusing to let drugs expire while patients die.”

IV. Precedent Powerhouse: Herbosa’s Innocence in Neon Lights

Let’s dive into the legal vault to prove Herbosa’s case isn’t just defensible—it’s a slam-dunk acquittal.

A. Health Secretary Showdowns

- Enrique Ona (2014): Ona faced Ombudsman flak over a ₱1 billion hospital procurement deal. Charges were dropped after he proved protocol compliance and no personal gain. Herbosa’s case mirrors this—reformist leader, vindictive complaints, clean intent.

- Garin and Duque (Dengvaxia): The Dengvaxia vaccine saga saw Garin and Duque hit with criminal and administrative charges. Many were dismissed or stalled for lack of criminal intent. Herbosa’s case is cleaner—no patient harm, just procedural gripes.

B. Drug Distribution Done Right

DOH v. Phil Pharmawealth upheld the DOH’s discretion to allocate resources non-standardly if public health goals are met. Herbosa’s Rotary Club move fits this mold, prioritizing access over bureaucracy.

C. Ombudsman’s Soft Spot for Health Heroes

In Ombudsman v. DOH Regional Director (2018), charges against a director for reallocating supplies during a typhoon were dropped for serving an urgent public need. Herbosa’s near-expiry drug allocation is a carbon copy.

D. The Vendetta Playbook

The “Political Weaponization” theme is old news. Reformist secretaries—Ona, Garin, Duque—faced similar Ombudsman attacks from insiders guarding their fiefdoms. Aguinaldo v. Ombudsman (G.R. No. 191065, 2013) warned against complaints as “harassment tools.” Herbosa’s accusers are reading from the same script.

Quotable Soundbite: “The Ombudsman’s files are stuffed with vendettas against reformers. Herbosa’s case is just another page in the playbook.”

V. Accuser Autopsy: Unmasking the Real Villains

Time to flip the script. The complainants—faceless DOH staff and “advocates”—aren’t crusaders; they’re likely bureaucrats with grudges. Their anonymity is a red flag. Are they sidelined by Herbosa’s reforms? Pals with rival civic groups? The Ombudsman should force disclosure under RA 6770, Section 12.

The timing stinks too. Herbosa’s been a bulldozer—pushing mental health, streamlining operations, and challenging DOH cronyism. The Rotary Club isn’t a shady outfit; it’s a humanitarian powerhouse. Why attack a life-saving partnership? It’s the “Bureaucratic Obstruction” narrative: insiders sabotaging a leader who threatens their cozy gigs.

VI. Policy Masterstroke: Herbosa’s Humanitarian Victory

Herbosa’s move wasn’t just legal—it was a public health grand slam.

A. Lifeline to the Vulnerable

The Rotary Club’s mission likely served communities where mental health care is a fantasy. RA 11223 mandates prioritizing the underserved, and Herbosa delivered. The complainants’ silence on patient outcomes screams bad faith.

B. Stopping the Waste Apocalypse

Letting ₱44.6 million in drugs expire is fiscal malpractice. Herbosa’s allocation reflects the Administrative Code (Book V, Title I)‘s call for efficient resource use.

C. Championing the Forgotten

Mental health is the DOH’s redheaded stepchild. Herbosa’s partnership extended care to the margins, fulfilling the “Mission Accomplished” narrative. Chavez v. Gonzales (G.R. No. 168338, 2008) praised officials who ditch rigidity for public welfare—Herbosa’s MO.

D. DOH’s North Star

The DOH’s 2025-2028 Strategic Plan prioritizes mental health and resource optimization. Herbosa’s move was a bullseye.

Quotable Soundbite: “While bureaucrats hoard rulebooks, Herbosa got drugs to patients who can’t afford a bus ticket to a clinic. That’s not corruption—it’s compassion.”

VII. The Final Verdict: Crush This Farce

This case is a legal mirage—big on noise, empty on facts. Herbosa’s actions are shielded by RA 11223 and the Administrative Code, backed by Supreme Court rulings like Duque and Phil Pharmawealth. The complaints are a procedural mess, lacking standing and evidence. Precedents from Ona to Dengvaxia show reformers triumph over vendettas. Policy-wise, Herbosa’s a hero, saving drugs and lives.

The Ombudsman should shred these complaints faster than a typhoon through a shanty. Better yet, turn the lens on the accusers—their motives stink of sabotage. Herbosa’s not corrupt; he’s a doctor who put patients above politics. Let him keep saving lives.

Recommendations:

- Dismiss with Prejudice: No probable cause under RA 6770, Rule II.

- Investigate the Accusers: Probe affiliations under RA 6770, Section 12.

- Fortify DOH Rules: Clarify emergency allocations to shield future leaders.

- Protect Trailblazers: Supreme Court guidance against frivolous complaints, per Aguinaldo.

Savage Legal Zinger:

“Herbosa’s not the bad guy—he’s the hero the bureaucracy wants to burn at the stake. The Ombudsman should torch these charges and let him save more lives.”

Key Citations

- Republic Act No. 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act): Defines graft, requiring proof of bad faith or injury.

- Republic Act No. 9711 (FDA Act): Regulates drug distribution, Section 11 on adulteration.

- Republic Act No. 10918 (Philippine Pharmacy Act): Governs pharmacy practices, Section 3 on distribution.

- Republic Act No. 6713 (Code of Conduct): Ethical standards for public officials.

- Republic Act No. 11223 (Universal Health Care Act): Grants Health Secretary broad powers, Section 5.

- Administrative Code of 1987 (EO No. 292): Emergency health powers, Book IV, Title VIII, Chapter 3.

- Ombudsman Act (RA 6770): Standing and transparency, Sections 12 and 16.

- Pharmaceutical and Health Care Association v. Duque (G.R. No. 173034, 2007): Health Secretary’s discretion.

- DOH v. Phil Pharmawealth (G.R. No. 182358, 2008): DOH resource allocation.

- Nepomuceno v. Duterte (UDK No. 16838, 2020): Emergency deviations.

- Aguinaldo v. Ombudsman (G.R. No. 191065, 2013): Frivolous complaints.

- Chavez v. Gonzales (G.R. No. 168338, 2008): Public welfare over rigidity.

Leave a comment