By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — August 5, 2025

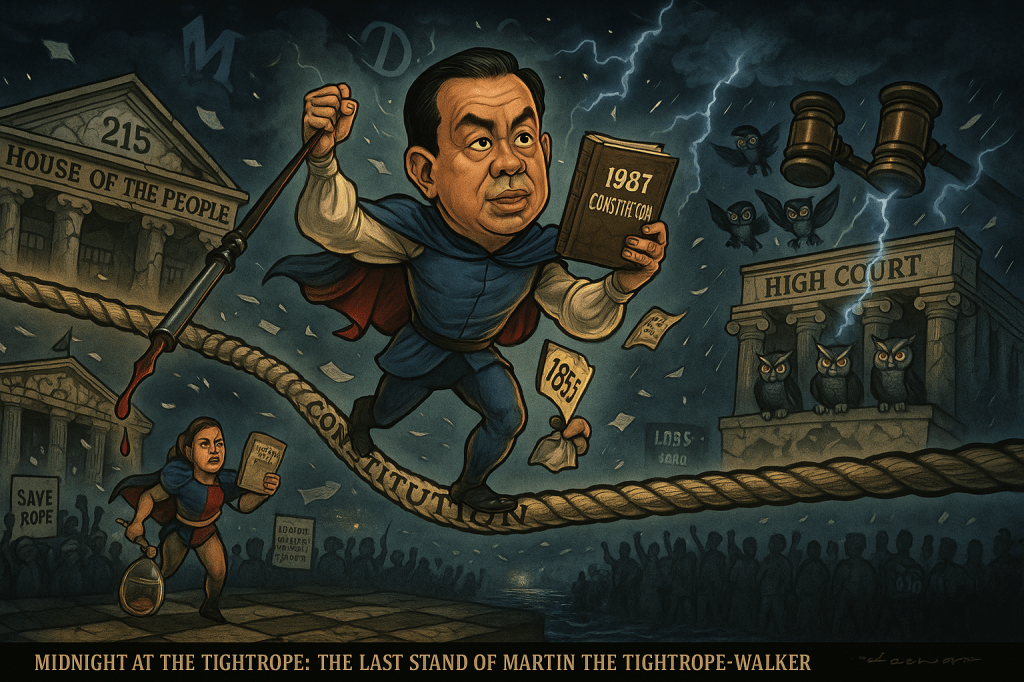

A midnight ruling by the Philippine Supreme Court didn’t just derail an impeachment—it ignited a constitutional firestorm that could reshape the nation’s democratic foundations. On July 25, 2025, the Court unanimously struck down the House of Representatives’ impeachment case against Vice President Sara Duterte, citing violations of the one-year bar rule and due process. The decision halted a Senate trial that could have altered the Philippines’ political trajectory. House Speaker Ferdinand Martin Romualdez, unyielding, countered with a Motion for Reconsideration, branding the ruling a judicial power grab that threatens the delicate balance of power. His stand—rooted in constitutional text, historical precedent, and a fierce defense of legislative authority—demands scrutiny for its legal weight and its stakes for a nation weary of elite power struggles.

This is no academic debate. When courts shield themselves from accountability, democracy bleeds. When legislatures wield impeachment as a blunt weapon, public trust frays. Romualdez’s response is not a revolt—it’s a circuit breaker against a judicial surge that risks short-circuiting the Constitution. Yet, the Supreme Court’s role as constitutional sentinel cannot be dismissed. Both sides claim to champion the rule of law, but their clash threatens to plunge Filipinos into deeper disillusionment. This exposé dissects Romualdez’s principled defiance, unravels the arguments on all sides, and lays bare the stakes for a democracy teetering on the edge.

Romualdez’s Last Stand: Defying Judicial Overreach

Speaker Romualdez’s response to the Supreme Court’s ruling is a constitutional call to arms. The 1987 Constitution, in Article XI, Section 3(1), grants the House the “exclusive power” to initiate impeachment proceedings—a mandate Romualdez argues was trampled when the Court nullified the February 5, 2025, impeachment complaint against Vice President Duterte. Signed by 215 lawmakers, the complaint accused Duterte of grave offenses: misuse of public funds, incitement to violence, and an alleged assassination threat against President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., his wife, and Romualdez himself. “We do not challenge the Court’s authority,” Romualdez declared in his August 4, 2025, statement, reported by JournalNews. “We seek only to protect the House—the people’s voice—in holding the powerful to account.”

Romualdez’s argument is anchored in textual originalism. The Constitution’s “exclusive” language leaves no room for judicial interference in how the House initiates impeachment. Historical precedent strengthens his case: in Francisco v. House (2003), the Supreme Court defined “initiation” as the House’s endorsement of a complaint, not its mere filing. The House adhered to this, archiving three earlier complaints (filed December 2024) only after transmitting the fourth, endorsed complaint on February 5, 2025. Romualdez contends the Court’s ruling—treating all four complaints as a single “initiation” triggering the one-year bar—rewrites Francisco and imposes a retroactive standard that undermines legislative autonomy.

On due process, Romualdez is equally forceful. The Constitution does not require the House to notify or hear from an official before transmitting impeachment articles to the Senate, where due process is fully afforded during trial. The 2012 impeachment of Chief Justice Renato Corona proceeded without pre-transmittal notice, a practice Romualdez cites as proof the Court’s new requirement is an ex post facto invention. “If these due process rules existed, the House would have complied,” he argued. “To invent them now is not just unfair—it’s constitutionally suspect.” This critique cuts deep: when courts craft rules retroactively, they risk appearing as guardians of their own immunity, especially since justices are impeachable under Article XI, Section 2.

Romualdez’s fight is not just legal—it’s a moral crusade. By defending the House’s prerogative, he positions himself as a steward of democratic accountability, ensuring no branch, not even the judiciary, can shield high officials from scrutiny. His Motion for Reconsideration, filed on August 4, 2025, is a rallying cry: “When grave charges are leveled against those in high office, it is the House—not the courts—that must ask: Is this official still worthy of the public’s trust?”

Tectonic Clash: Peeling Back the Layers of a Democratic Crisis

For Romualdez: A Fortress of Constitutional Logic

Romualdez’s arguments are a bulwark of constitutional design. Article XI, Section 3(1) grants the House sole authority to initiate impeachment, a process shielded from judicial oversight unless it involves “grave abuse of discretion” (Bondoc v. Pineda, 1991). The Court’s intervention, by redefining “initiation” to include unendorsed complaints, breaches this exclusivity. If the judiciary can dictate how the House conducts its internal proceedings, what’s next? Could it mandate how bills are debated or votes counted? This slippery slope threatens the separation of powers, a bedrock of Philippine democracy.

On due process, Romualdez’s logic is ironclad. Impeachment is bifurcated: the House accuses, the Senate tries. Requiring notice before transmittal burdens the House with a judicial role it was never meant to play. Historical practice—Corona’s impeachment, Estrada’s in 2000—shows no such requirement existed. The Senate trial, with its adversarial structure, ensures fairness, not the House’s preliminary vote. Demanding otherwise risks paralyzing impeachment, a tool designed to swiftly address public malfeasance.

The Court’s retroactive rule-making is Romualdez’s trump card. By declaring the House’s process unconstitutional based on a novel interpretation of the one-year bar, the Court punishes the House for rules it couldn’t have foreseen. This violates basic fairness, a principle the Court claims to uphold. Romualdez’s warning—that such judicial overreach could “write the terms of [the Court’s] own immunity”—is a stark reminder that justices, too, are accountable to the people.

Against Romualdez: The Court’s Shield of Oversight

The Supreme Court’s defenders argue it acted within its mandate. Article VIII, Section 1 empowers the Court to review acts of co-equal branches for constitutional compliance. The House’s handling of four complaints—three filed in December 2024, archived only after the fourth’s transmittal—suggests manipulation to skirt the one-year bar (Article XI, Section 3[5]). The Court, led by Senior Associate Justice Marvic Leonen, ruled that these complaints constituted a single proceeding, terminated on February 5, 2025, barring new filings until 2026. This interpretation, while broad, aims to prevent abuse, ensuring officials aren’t harassed by successive complaints (Rappler, July 2025).

Due process is a flashpoint. The Court argued Duterte was denied “fundamental fairness” by not receiving notice or a chance to respond before the Senate received the articles. While Romualdez cites historical practice, the Court counters that evolving standards of fairness apply even to impeachment, a process with profound consequences like removal and a lifetime ban from office. This view aligns with Angara v. Electoral Commission (1936), which emphasized due process in quasi-judicial proceedings.

Critics also highlight political weaponization. The impeachment’s timing—after Duterte’s public feud with Marcos and Romualdez—suggests a vendetta. Allegations of graft, incitement, and assassination threats surfaced amid a bitter Marcos-Duterte rift, with 215 signatures secured in 48 hours. The Court’s scrutiny, in this context, checks impeachment as a political tool, especially given Duterte’s 2028 presidential ambitions (BBC, July 2025).

Yet, these arguments waver under scrutiny. The Court’s redefinition of “initiation” contradicts Francisco, risking legal uncertainty. Its due process requirement, absent from the Constitution, feels like judicial overreach. And while political motives may taint the impeachment, the House’s procedural compliance—215 signatures, verified complaint—lends it legitimacy. The Court’s ruling, by halting the process, may shield Duterte for political, not legal, reasons, fueling perceptions of judicial bias.

The Stakes: A Democracy Hanging by a Thread

This clash is a crucible for Philippine democracy. The separation of powers teeters. If the Court’s ruling stands, it could embolden judicial oversight of legislative processes, eroding the House’s autonomy. If Romualdez prevails, impeachment risks becoming a political bludgeon, wielded by whichever faction controls Congress. Either outcome could destabilize the delicate balance among co-equal branches.

Public trust is the silent victim. Filipinos, battered by elite-driven politics, see this as another chapter in the Marcos-Duterte saga. The impeachment, sparked by Duterte’s alleged threat to kill Marcos, his wife, and Romualdez, is less about accountability than clan warfare. The Court’s intervention, while cloaked in constitutional rhetoric, fuels suspicions of self-preservation—after all, justices are impeachable too. When institutions bicker, democracy’s lifeblood—public faith—drains away. A 2024 survey showed trust in the judiciary at 35%, barely above Congress at 32%. Further erosion could cripple governance.

The 2028 elections cast a long shadow. Duterte, a leading contender, emerges as a political martyr, her persecution narrative strengthened. A Senate trial could have barred her from running, reshaping the electoral landscape. Romualdez’s fight, while constitutionally robust, risks alienating voters if seen as a Marcos proxy. The House’s 215 signatures, including Marcos’s son Sandro, deepen perceptions of a vendetta. Yet, by defending the House’s role, Romualdez keeps accountability alive, ensuring no official is untouchable.

The human cost is profound. Filipinos, grappling with inflation, territorial disputes, and a fragile post-COVID economy, deserve institutions that prioritize their needs over power plays. The impeachment’s allegations—Duterte’s misuse of funds, her silence on China—reflect real grievances, but their resolution is mired in legalism. Democracy thrives on clarity, not courtroom dramas.

Charting the Way Forward: Saving Democracy from Itself

To avert a constitutional crisis, all sides must act with restraint and vision:

- The House: Codify impeachment procedures through an Impeachment Procedure Act, as proposed by iDefend, specifying timelines, notice requirements, and judicial review limits. This preserves legislative autonomy while preempting future clashes.

- The Supreme Court: Rule narrowly on Romualdez’s motion, clarifying the one-year bar without rewriting constitutional roles. Former Justice Antonio Carpio’s advice is sound: affirm judicial review but avoid retroactive rule-making. A transparent decision could restore public trust.

- Filipinos: Demand accountability beyond elite squabbles. Civil society should push for a Citizen Impeachment Council, as suggested by academics, to vet complaints before House votes, ensuring impartiality. Transparency—public hearings, clear rulings—can rebuild faith in a battered system.

The Final Reckoning: A Tightrope Over the Abyss

Romualdez’s stand is a defiant defense of the House’s constitutional turf, rooted in text, precedent, and a commitment to accountability. The Supreme Court’s ruling, while legally defensible, risks overstepping into legislative territory, setting a precedent that could shield the powerful—including justices themselves. Both sides wield truths, but neither is infallible.

The Filipino people, caught in this crossfire, deserve more than a spectacle. They deserve a democracy where institutions check each other without breaking the system apart. Romualdez’s fight is not just for the House but for the principle that no official is above scrutiny. Yet, the Court’s caution against abuse reminds us that power, unchecked, can corrupt even the righteous. The tightrope of democracy holds only if both sides walk with care, not hubris. For now, Romualdez’s constitutionalist posture is the stronger thread, weaving accountability back into a fraying national fabric. But the final knot—whether it binds or unravels—depends on whether institutions listen to the people they serve.

Word count: 1,200

Key Citations

- 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines, Article XI – Outlines the impeachment process, including the House’s exclusive power to initiate.

- Francisco v. House of Representatives (2003) – Defines “initiation” as House endorsement of an impeachment complaint.

- Bondoc v. Pineda (1991) – Limits judicial review of legislative acts to cases of grave abuse of discretion.

- Angara v. Electoral Commission (1936) – Emphasizes due process in quasi-judicial proceedings.

- JournalNews: “Speaker Romualdez: House will not bow in silence” – Details Romualdez’s response to the Supreme Court’s ruling.

- Rappler: “Supreme Court bars Sara impeachment, can be refiled next year” – Reports the Supreme Court’s decision and its rationale.

- BBC: “Philippine court strikes down landmark impeachment bid against Sara Duterte” – Provides international context for the ruling.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

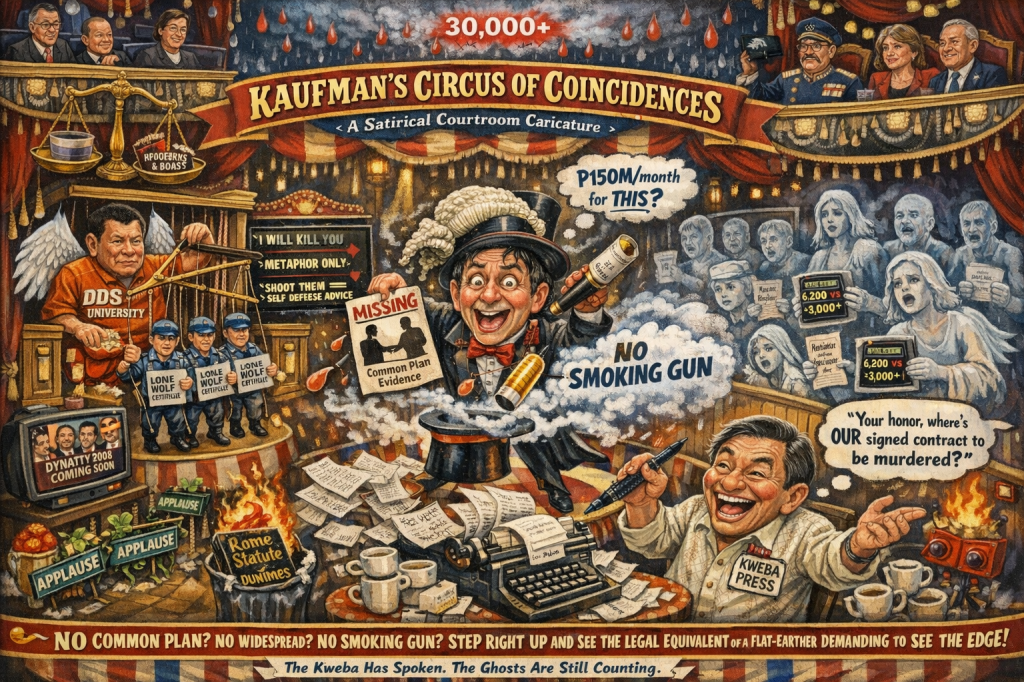

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment