By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — August 6, 2025

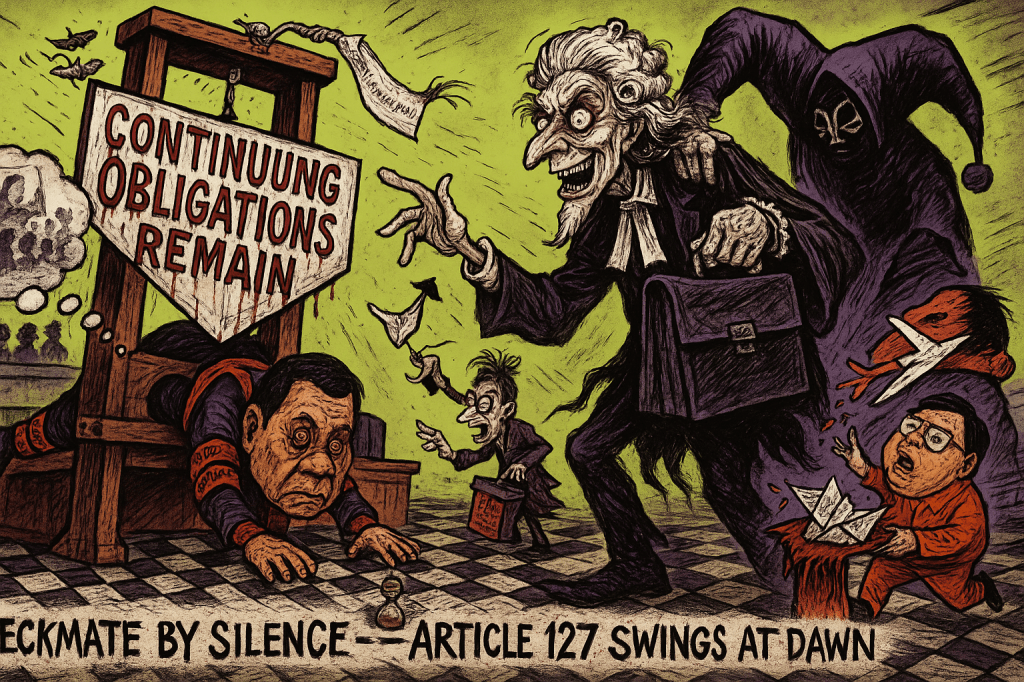

When Nicholas Kaufman, Rodrigo Duterte’s lead counsel, declared his team would call no witnesses at the September 23, 2025, confirmation of charges hearing, the courtroom didn’t just gasp—it smelled blood. Is this a masterstroke to set a trap for trial, or a wounded defendant waving a white flag? Below, we carve open the defense’s high-risk gambit, shred their jurisdictional mirage, and expose the political machinations. The ICC‘s blade is sharpened, and Duterte’s team is playing a dangerous game where Article 127‘s three words—”continuing obligations remain”—could sever their hopes.

Kaufman’s No-Witness Gambit: Tactical Genius or Fatal Surrender?

Kaufman’s decision to rely solely on documentary evidence, forgoing live witnesses or Article 31 defenses (mental incapacity, duress, self-defense), is a calculated bet teetering on a cliff’s edge. The defense argues it’s playing by ICC Rule 126(2), which governs confirmation hearings and requires only a “reasonable basis” to believe crimes were committed—not a full trial of credibility. By withholding witnesses, Kaufman avoids tipping his hand, preserving testimony for a trial where the burden of proof is higher.

- Defense’s Logic: The Lubanga case (ICC-01/04-01/06) supports this. Lubanga’s team called no witnesses at confirmation, yet charges were confirmed, with defenses reserved for trial. Kaufman’s silence could be a page from this playbook—why expose witnesses when documents might challenge jurisdiction or procedural flaws?

- The Risk: Silence risks signaling weakness. Neri Colmenares, counsel for victims’ families, calls it a “practical admission” of guilt, arguing Duterte’s refusal to contest the 6,000–30,000 death toll from the drug war (OTP Report, Dec 2020) implies complicity.

The prosecution’s case is a sledgehammer: over 200 pieces of evidence, including police reports and witness affidavits (OTP, May 2025). Article 67(1)(e) guarantees Duterte’s right to present evidence, but Kaufman’s approach hands the prosecution a narrative victory. The Lubanga precedent cuts both ways: while the defense survived confirmation, it faced an ironclad prosecution case. Kaufman’s strategy is a tourniquet, bleeding credibility.

Verdict: Kaufman’s approach is legally sound but politically disastrous. It preserves trial flexibility but alienates victims and risks a confirmation slam-dunk by Pre-Trial Chamber I, led by Judge Iulia Motoc.

Article 31’s Ghost: Why Duterte Won’t Plead Insanity

Neri Colmenares claims Duterte’s failure to invoke Article 31 defenses—mental incapacity, duress, or self-defense—equals an admission of guilt. Article 67(1) ensures a fair defense, including grounds for excluding responsibility under Article 31. Kaufman’s avoidance prompts Colmenares to argue it’s a tacit acknowledgment of responsibility for the drug war’s atrocities.

- Defense’s Calculation: Article 31 defenses aren’t mandatory at confirmation and are often reserved for trial. In Bemba (ICC-01/05-01/08), the defense raised Article 31 grounds (mistake of fact) only at trial, forcing the prosecution to prove intent. Raising mental incapacity or duress now could lock Duterte into a weak narrative, alienating his domestic base, which sees him as a strongman. Duterte’s boasts about commanding Davao’s death squads make such defenses laughable.

- Prosecution’s Edge: The OTP alleges Duterte’s role as “founder and head” of the Davao Death Squad, responsible for murders from November 2011 to March 2019 (Article 7(1)(a)). Kaufman’s silence leaves this unchallenged at a stage where a weak defense could muddy the waters.

Verdict: Kaufman’s choice preserves trial defenses but leaves Duterte exposed at confirmation. Colmenares’ “admission” charge is overstated—Article 67 doesn’t compel early defenses—but the optics are brutal. The defense dances on a razor’s edge.

The Withdrawal Mirage: Kaufman’s Jurisdictional Gambit Shredded

Kaufman argues the ICC lost jurisdiction when the Philippines withdrew from the Rome Statute in March 2018, effective March 17, 2019. He cites Article 12(2), claiming the Court can only exercise jurisdiction over state parties at the time of proceedings. Since the investigation was authorized in 2021, post-withdrawal, Kaufman says the ICC’s reach is null. This is a jurisdictional mirage, and Article 127(1) is the guillotine that slices it apart.

- Legal Reality: Article 127(1) states withdrawal “shall not affect any cooperation with the Court in connection with criminal investigations… commenced prior to the date on which the withdrawal became effective.” The Philippines was a state party from November 1, 2011, to March 16, 2019, covering Duterte’s drug war. The OTP‘s preliminary examination began in February 2018 (ICC Statement, 2018), and the December 2020 OTP Report confirmed crimes against humanity (murder, torture, rape) from July 2016 to March 2019.

- Precedents: In Burundi (ICC-01/17), the ICC retained jurisdiction over pre-2017 withdrawal crimes, authorizing an investigation days before the exit. The Kenya case upheld jurisdiction for pre-withdrawal crimes. Kaufman’s Article 12(2) argument is a sleight of hand—Article 127(2) preserves jurisdiction for matters “under consideration” before withdrawal.

The Harry Roque Distraction: A Fugitive’s Last Gasp?

Harry Roque, Duterte’s fugitive former spokesperson, has filed unauthorized motions (e.g., a case against the Netherlands), muddying the defense. Kaufman calls Roque “irrelevant,” but his antics highlight internal chaos, risking Dutch cooperation needed for Duterte’s interim release.

Verdict: Kaufman’s argument is a legal corpse. Article 127 and Burundi/Kenya precedents confirm ICC jurisdiction over 2011–2019 crimes. The OTP’s 2020 report is a kill shot. Kaufman’s team is shouting into a void.

Victims vs. Realpolitik: The Human Cost of Delay

Justice Delayed = Justice Denied

Kristina Conti, ICC assistant counsel for victims, channels the outrage of families whose loved ones were slaughtered in Duterte’s drug war. Article 68(3) mandates considering victims’ interests. Kaufman’s silence—no witnesses, no defenses—mocks this, prolonging agony for families facing police obstruction and threats. Conti’s fury is justified: delays erode trust in the ICC‘s process. The OTP‘s evidence, including witness testimonies of systematic killings, demands a response, not paper-pushing.

The Sara Duterte Factor: A 2028 Election Subplot?

Kaufman’s delays shield Vice President Sara Duterte‘s 2028 presidential ambitions. The Marcos-Duterte rift, erupting in 2024 over funding and alleged death threats (Reuters, 2024), has turned this case into a political crucible. Sara’s condemnation of her father’s arrest as an “affront to sovereignty” (Inquirer, 2025) taps nationalist sentiment. Kaufman’s jurisdictional fight buys time, softening the case’s impact on Sara’s campaign. A dismissed case could martyr Duterte; a trial could tarnish the family brand.

Verdict: The defense’s tactics brutalize victims, violating Article 68’s spirit. The Sara subplot is real—Kaufman’s delays are a political lifeline, but they risk backfiring if the ICC proceeds.

Nuclear Options: The ICC’s Crossroads

If the ICC Dismisses

A jurisdictional win would be a catastrophe for international justice, emboldening dictators to withdraw from the ICC, as Hungary did in 2024 (Euronews, 2024). Figures like Putin or Netanyahu could see exit as immunity. The Burundi precedent shows ICC resolve, but a loss here would weaken it.

If It Proceeds

A trial would be the ICC‘s “Nuremberg Moment” for Southeast Asia, holding a former head of state accountable. But it risks martyring Duterte domestically, where his base venerates his strongman image. In Kenya, William Ruto leveraged his ICC case to win the presidency in 2022. Duterte’s conviction could galvanize Sara’s 2028 run or fracture the family’s grip.

Verdict: Dismissal would cripple the ICC’s clout. A trial could cement its legacy but risks political blowback. The Court must act decisively.

Recommendations

- For the Court: Demand Kaufman justify why documentary evidence rebuts the OTP‘s case—or treat it as a de facto surrender under Article 61(7). The ICC must not let gamesmanship trump justice.

- For Victims: Conti should rally families to demand transparency under Article 68, forcing Kaufman to engage or face condemnation.

- For History: Frame this as the ICC‘s defining moment. A conviction would signal that Southeast Asia’s strongmen can’t hide behind sovereignty.

Final Verdict: Outmaneuvered or 4D Chess?

Kaufman’s defense is a high-stakes bluff crumbling under the ICC‘s jurisdictional guillotine. The no-witness strategy, while procedurally valid, hands the prosecution a narrative win, alienating victims and risking confirmation. The jurisdictional gambit is a mirage—Article 127 and Burundi/Kenya precedents bury it. Politically, the defense buys time for Sara Duterte‘s 2028 bid, but it’s desperate against an OTP armed with a 2020 report and 200+ pieces of evidence. Duterte’s team isn’t playing 4D chess—they’re stalling on a sinking board, hoping for a miracle. The clock ticks toward September 23, and they’ve brought a pen to a gunfight.

Key Citations

- Rome Statute: Full Text

- Article 7 (Crimes Against Humanity)

- Article 12 (Jurisdiction)

- Article 31 (Defenses)

- Article 61 (Confirmation)

- Article 67 (Rights of Accused)

- Article 68 (Victims’ Rights)

- Article 127 (Withdrawal)

- ICC Rules of Procedure and Evidence: Rule 126(2)

- OTP Report, Dec 2020: Philippines Preliminary Examination

- ICC Statement, 2018: Philippines Preliminary Examination

- Cases:

- News:

Disclaimer: This is legal jazz, not gospel. It’s all about interpretation, not absolutes. So, listen closely, but don’t take it as the final word.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment