By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — August 15, 2025

“A high school dropout just lost control of the Philippine Constitution. Thank God.”

Sen. Robinhood Padilla—former action star, convicted felon turned politician, constitutional law novice—has been stripped of his gavel as chair of the Senate’s most crucial committee. In his place: Harvard-trained lawyer Kiko Pangilinan, a man who actually understands the document he’s now tasked with potentially rewriting. The swap happened quietly on a Tuesday afternoon, but its implications could reshape Philippine democracy forever.

The switch, announced during a Senate plenary session, represents more than a changing of the guard. It’s a confession of failure, a belated recognition that placing the Philippines’ most sacred document in the hands of someone utterly unqualified was a catastrophic mistake from the start.

🎬 From Silver Screen to Senate Floor: The Padilla Catastrophe

Let’s be unflinchingly clear about what Robin “Robinhood” Padilla’s tenure represented: institutional vandalism masquerading as populism. Here was a high school dropout—a man who never finished college, much less studied constitutional law—given control over the very document that defines Philippine democracy. The appointment wasn’t just tone-deaf; it was an insult to every lawyer, every constitutional scholar, and every citizen who believes competence should matter in governance.

The numbers tell the story of his spectacular incompetence. Under Padilla’s watch, the constitutional amendments committee became a laughingstock. International media didn’t miss the irony—here was a former action star, whose most memorable political act was getting a presidential pardon for illegal firearms possession, attempting to rewrite a nation’s supreme law. The optics were so damaging that foreign investors began questioning the Philippines’ commitment to serious governance.

But Padilla’s failures went beyond mere symbolism. His committee produced virtually nothing of substance. When he did attempt legislative work, it was marked by the kind of elementary errors that would embarrass a first-year law student. His procedural missteps and inability to command respect from fellow senators rendered the committee effectively neutered during a critical period when constitutional reform actually mattered.

Perhaps most problematic was Padilla’s alignment with the House’s charter change agenda. Rather than asserting Senate independence, Padilla became a willing participant in what many saw as an overly aggressive constitutional reform push. His endorsement of widely criticized “People’s Initiative” campaigns and his appearances in pro-administration constitutional videos revealed a man more interested in partisan cooperation than rigorous constitutional analysis.

The final straw came when Padilla filed what legal observers called a “befuddled” petition to the Supreme Court, seeking clarity on constitutional procedures he should have mastered before accepting the chairmanship. The petition, riddled with procedural errors, perfectly encapsulated his tenure: well-intentioned perhaps, but woefully out of his depth.

⚖️ The Harvard Graduate vs. The High School Dropout: Why Credentials Matter

Enter Francis “Kiko” Pangilinan—Harvard-trained lawyer, former Senate minority leader, and everything Padilla was not: qualified. “I accept this responsibility with humility and a firm resolve to safeguard the democratic ideals enshrined in our Constitution,” Pangilinan said in a statement. The contrast couldn’t be starker. Where Padilla offered celebrity and blind loyalty, Pangilinan brings legal pedigree and institutional memory.

This isn’t to say Pangilinan is without flaws. His Liberal Party background makes him a natural target for administration allies who prefer their constitutional reform served with fewer questions asked. Critics point to his past positions on juvenile justice reform and his occasional tendency toward political grandstanding. But these are the criticisms of a functioning politician, not the fundamental incompetence that defined his predecessor.

Pangilinan’s strength lies not just in his credentials but in his approach. Pangilinan said he would conduct a series of public consultations, which would include input from constitutional experts, civil society representatives, business groups, local government units, and ordinary citizens. This consultative methodology—the antithesis of Padilla’s top-down approach—offers hope that constitutional reform might finally be conducted with the gravity it deserves.

The senator’s dual committee responsibilities do raise legitimate concerns about bandwidth. Chairing both Agriculture and Constitutional Amendments in a polarized political environment would challenge even the most capable legislator. But overextension is a problem of success, not incompetence—a refreshing change from the Padilla era.

💥 Constitutional Crisis at Breaking Point: What’s Really at Stake

This leadership change occurs at a moment of maximum peril for Philippine democracy. The country faces a constitutional crisis that goes far beyond technical legal questions. The 1987 Constitution, drafted in the shadow of the Marcos dictatorship, contains provisions that increasingly conflict with the realities of modern governance and global economics.

Foreign investment restrictions that made sense in the post-martial law era now strangle economic growth. Constitutional ambiguities around impeachment procedures create opportunities for political manipulation. Meanwhile, opposition lawmakers contend that the House of Representatives has weaponized charter change as a tool for term extensions and power consolidation.

The change was made in light of Senate Minority Leader Vicente Sotto III’s remarks that he would favor amending the Charter under certain conditions. This development reveals the precarious political dynamics at play. Sotto’s conditional support for constitutional reform, combined with Senate President Escudero’s apparent frustration with excessive House influence, has created an opening for serious constitutional dialogue.

But will Pangilinan prove equal to this moment? The early signs are encouraging. His commitment to transparency and consultation suggests an understanding that constitutional legitimacy requires popular consent, not elite manipulation. His legal background provides the technical competence that Padilla so obviously lacked. Most importantly, his track record suggests he won’t be anyone’s rubber stamp.

🌏 Ripple Effects: How One Personnel Change Could Reshape a Nation

This personnel change reverberates far beyond the Senate chamber. For foreign investors watching the Philippines navigate constitutional reform, the replacement of an unqualified populist with a credentialed lawyer signals a return to institutional seriousness. Markets respond to competence, and Pangilinan’s appointment may help restore confidence in the reform process.

For ordinary Filipinos, the change offers hope that constitutional reform—if it comes—will be conducted with their interests in mind rather than as elite horse-trading. “The Constitution belongs to the people, and any move to change it must be anchored on their aspirations and welfare. It must also undergo a thorough, principled, and participatory process,” the senator added. These aren’t just nice words; they represent a fundamentally different philosophy from the Padilla approach.

But dangers remain. The House of Representatives, emboldened by years of constitutional momentum, won’t easily adjust its timeline. House leaders have invested significant political capital in charter change and may pressure Pangilinan to accelerate the process, potentially compromising the consultative approach he has promised.

Similarly, entrenched interests on both sides of the political spectrum have reasons to either accelerate or sabotage constitutional reform. Progressive groups fear economic liberalization will benefit only foreign corporations and local oligarchs. Conservative forces worry that any constitutional change opens the door to political instability.

🎯 The Action Plan: How Pangilinan Can Save Philippine Democracy

Pangilinan must thread an impossibly narrow needle. He needs to demonstrate that serious constitutional reform is possible without sacrificing democratic legitimacy. Here’s how he can succeed:

- Flood the zone with transparency. Every committee hearing should be livestreamed. Every submission from the public should be published online. Every expert consultation should be documented and made available for public scrutiny. Sunlight remains democracy’s best disinfectant.

- Prioritize economic reforms while blocking political power grabs. The Philippines desperately needs constitutional changes that allow greater foreign investment in key sectors. These reforms could unlock billions in development funding and create millions of jobs. But any package that includes term extensions or other self-serving political amendments should be dead on arrival.

- Build genuine bicameral independence. The House has maintained an aggressive timeline for constitutional reform. Pangilinan must reassert the upper chamber’s equal role in the process, ensuring that Senate deliberations proceed at a pace that allows for thorough analysis and public input.

- Create citizen oversight mechanisms. Constitutional reform can’t be left to politicians alone. Independent monitoring groups, civil society organizations, and academic institutions must have formal roles in evaluating proposals and tracking the process.

For the Senate as an institution, this moment demands more than just personnel changes. The chamber must formalize qualification requirements for sensitive committee positions. Never again should someone utterly unqualified for a role be handed such enormous responsibility simply because of celebrity status or political connections.

For Filipino citizens, the message is clear: engagement is not optional. Constitutional reform—whether it succeeds or fails—will shape the country for generations. The public cannot afford to be passive spectators while politicians determine their constitutional future.

🔮 The Ultimate Question: Reform or Ruin?

As Pangilinan assumes his new role, the fundamental question isn’t whether he’s better qualified than his predecessor—that bar is embarrassingly low. The question is whether the Philippines has the political maturity to conduct constitutional reform in the public interest rather than as elite manipulation.

The early signs are cautiously optimistic. Pangilinan’s legal background, commitment to consultation, and institutional independence suggest that serious constitutional dialogue may finally be possible. But optimism must be tempered by realism about the forces arrayed against transparent reform.

The Philippines stands at a constitutional crossroads. One path leads toward thoughtful, inclusive reform that addresses the country’s real challenges while preserving democratic values. The other leads toward elite capture of constitutional change, serving narrow interests at the expense of national welfare.

Pangilinan now carries the Constitution in his hands. Whether this becomes the reform that saves Philippine democracy—or the missed chance that dooms it—depends on his ability to resist the siren call of political expediency and serve the Filipino people with the gravity this moment demands.

The action star has left the constitutional stage. Now it’s time for the real work to begin.

📚 Key Citations

- Primary News Source: Pangilinan replaces Padilla as Senate constitutional amendments chair – Philippine Daily Inquirer, August 12, 2025

- Context on Charter Change: Cha-cha needed to address Constitution’s unicameral wordings – Puno – Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Presidential Position: Marcos open to Charter change via Con-con to close loopholes – Palace – Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Historical Context: Marcos: Why the row? Senate to lead Cha-cha – Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Senate Official Website: Philippine Senate – For committee structures and proceedings

- Constitutional Text: 1987 Philippine Constitution – Official Gazette

- Legal Analysis Resources: Supreme Court of the Philippines – For constitutional jurisprudence and decisions

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

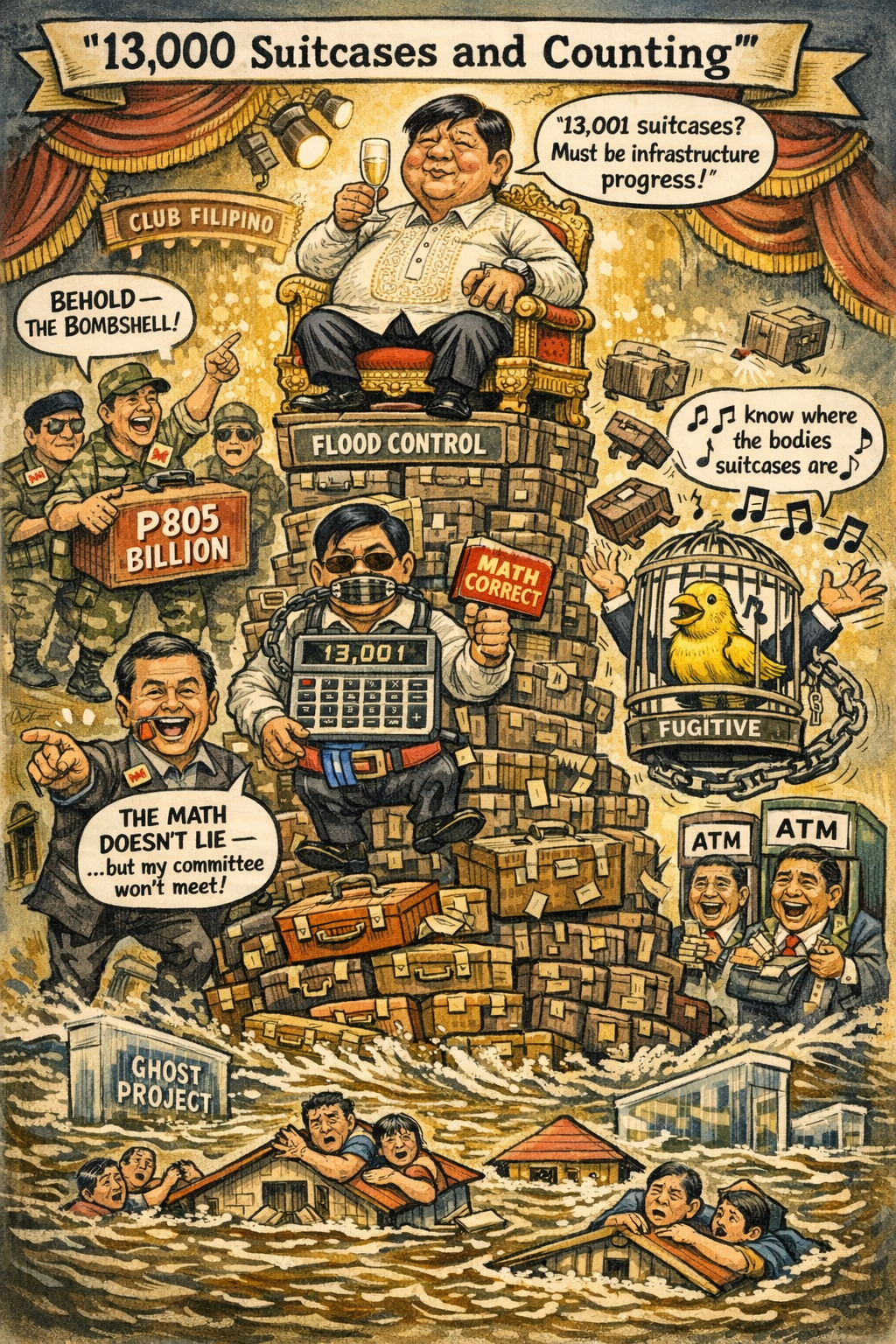

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

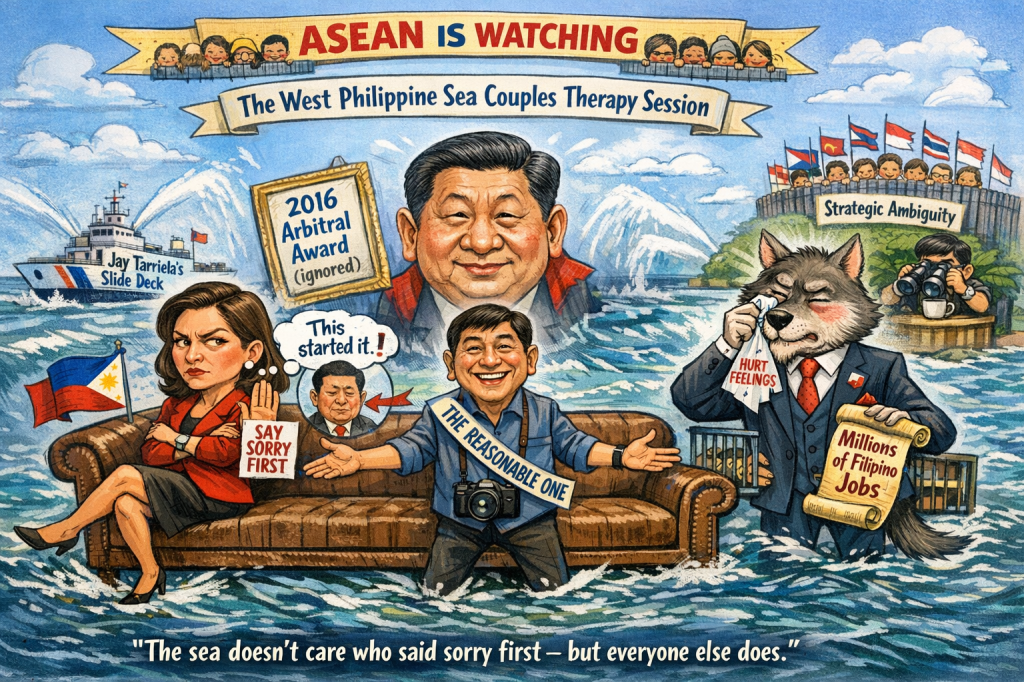

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment