By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — August 24, 2025

WELCOME to another Kweba ng Katarungan takedown, where we slice through the Marcos administration’s latest stunt with a legal machete. Executive Order (EO) 92, signed on August 13, 2025, conjures up the Office of the Presidential Adviser on Pasig River Rehabilitation (OPAPRR), a shiny new bureaucracy tasked with reviving the Pasig River from its biologically dead abyss. Because nothing screams “save the planet” like appointing a failed housing czar with Marcos family ties to helm a legally dubious, tourism-obsessed initiative, right? Let’s dive into the legal, ethical, and political muck to expose EO 92 as either a bold environmental gambit or a crony-fueled mirage.

1. Constitutional Con Job or Legit Executive Flex?

Constitutional and Statutory Foundations: Built on Sand?

EO 92 leans on Article VII, Section 17 of the 1987 Constitution, granting the President control over executive departments, and Book III, Section 31 of the Administrative Code of 1987, allowing reorganization within the Office of the President (OP). The Marcos camp claims this gives him free rein to create OPAPRR as a coordinating body. Sure, cases like Larin v. Executive Secretary (G.R. No. 112745, 1997) and Buklod ng Kawaning EIIB v. Zamora (G.R. No. 142801, 2001) give the President some leeway to shuffle OP units. But here’s the kicker: creating a new office with a Cabinet-rank adviser, complete with “emoluments of a Secretary,” smells like a de facto department head, which Biraogo v. Philippine Truth Commission (G.R. No. 192935, 2010) flags as executive overreach without legislative approval. Congress controls the purse under Article VI, Section 25(5). Where’s the specific appropriation for OPAPRR? Tucked in the vague “organization/creation” clause of Section 93, FY 2025 GAA? Good luck selling that to the Supreme Court.

Separation of Powers: Sneaking Past Congress’ Goalposts

EO 92’s creation of OPAPRR and its rejiggered Inter-Agency Council for Pasig River Urban Development (IAC-PRUD) looks like a sly end-run around Congress. Pelaez v. Auditor General (G.R. No. L-23825, 1965) is blunt: the President can’t create new offices with substantive powers without legislative consent. OPAPRR’s “coordinate, harmonize, and monitor” mandate sounds harmless, but if it starts bossing around agencies like DENR or MMDA—statutory bodies under RA 9275 (Clean Water Act) and RA 7924 (MMDA Charter)—it’s skating on ultra vires ice. Why not just beef up existing agencies? Oh, wait, new offices mean new patronage slots and a Marcos-branded ribbon to cut.

Supreme Court Smackdown Looming?

The Supreme Court’s been here before. Biraogo struck down an EO for targeting one group without equal protection—EO 92’s Pasig-only focus raises similar “why this river?” questions. And in MMDA v. Concerned Residents of Manila Bay (G.R. No. 171947-48, 2008), the Court mandated existing agencies to clean up Manila Bay and its tributaries, including Pasig. EO 92’s new office could be seen as dodging this judicial order, creating a parallel structure that muddies accountability. Is this about complying with the Court or just looking busy while the river stays dead?

2. Environmental Laws vs. Tourism Fantasies: A Legal Trainwreck

Statutory Showdown: EO 92 vs. the Law

EO 92’s vision of a “commercial and tourism hub” is a developer’s dream but a nightmare for environmental laws. Here’s the clash:

- RA 9275 (Clean Water Act): DENR leads water quality management, yet OPAPRR takes the wheel. If it overrides DENR’s powers, it’s ultra vires, as LLDA v. CA (G.R. No. 120865, 1996) upheld LLDA’s jurisdiction over Pasig’s basin.

- RA 9003 (Ecological Solid Waste Management Act): LGUs and MMDA handle waste, a major Pasig polluter. EO 92’s vague coordination risks sidelining these roles.

- RA 7279 (Urban Development and Housing Act): Riverbank clearing for parks means evicting settlers. RA 7279 demands notice, consultations, and relocation—EO 92’s silence is deafening. Chavez v. PEA (G.R. No. 133250, 2002) stresses social justice for the poor.

- PD 1067 (Water Code): Mandates 3-meter urban easements for public use. Commercializing these violates the public trust doctrine from Manila Bay.

- PD 1586 (EIS System): Major projects need ECCs with full impact assessments. EO 92’s silence invites writs of kalikasan for skipping cumulative reviews.

Table: EO 92’s Legal Collisions

EO 92’s Legal Collisions TableTable: EO 92’s Legal Collisions

| EO 92 Provision | Conflicting Law/Regulation | Violation Risk |

|---|---|---|

| OPAPRR coordinates rehabilitation | RA 9275, RA 7924, RA 4850 (LLDA) | Usurps statutory mandates, ultra vires |

| Commercial/tourism hub | PD 1067, Manila Bay ruling | Encroaches on public easements, prioritizes profit |

| No relocation plan | RA 7279 | Violates notice, consultation, relocation rules |

| No EIS compliance | PD 1586 | Risks writs of kalikasan for skipping ECCs |

Superseding Mandates: A Czar’s Power Grab?

By placing OPAPRR above DENR, MMDA, and LLDA, EO 92 risks creating a super-agency that overrides statutory powers. Manila Bay already mandates these agencies to clean Pasig—why not enforce that instead of crowning a new czar? If OPAPRR issues directives, it’s stepping into LLDA v. CA territory, where the Court quashed attempts to dilute LLDA’s powers. “Harmonization” sounds like code for “I’m in charge,” especially with a Cabinet-rank adviser cozying up to Malacañang. Why does this feel like a Marcos loyalist running the show?

3. Cronyism and Political Posturing: Ethical Rot in the Riverbed

Jose Acuzar: Nepotism’s New Poster Boy?

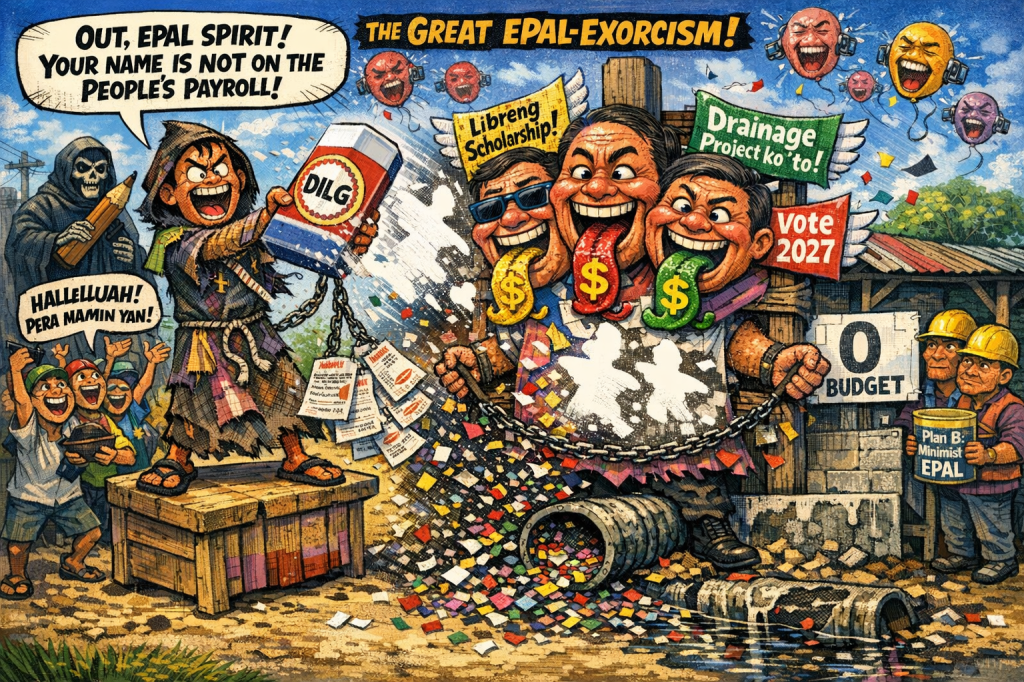

Meet Jose “Jerry” Acuzar, EO 92’s Presidential Adviser, fresh from “underdelivering” as DHSUD Secretary, as per Executive Secretary Lucas Bersamin. Oh, and he’s the brother-in-law of Paquito Ochoa, law partner of First Lady Liza Araneta-Marcos. Nothing screams “merit and fitness” under RA 6713, Section 4 like appointing a family-connected flop to a high-profile gig. Section 7 of RA 6713 bans conflicts of interest, including appointments based on ties rather than competence. Acuzar’s DHSUD failures—missing housing targets—don’t exactly inspire confidence he’ll revive a river dead since the ’90s. Why him, Marcos? Saving the Pasig or rewarding cronies?

Legacy-Building 101: A Marcos Political Ploy

EO 92’s timing stinks of desperation. With Marcos’s approval ratings sinking amid inflation and economic gripes, “Pasig Bigyang Buhay Muli” is a classic legacy play. Infrastructure projects are the Marcos family’s catnip—recall Ferdinand Sr.’s PD 274 (1973) on Pasig preservation. Now, Bongbong’s doubling down, despite the Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission (PRRC) collapsing post its 2018 Asia RiverPrize win. Why expect success when history screams failure? The tourism focus feels like a voter-wooing stunt, not the gritty pollution fight needed. RA 6713, Section 4(a) demands public interest over personal gain—EO 92’s political sheen fails that test.

Transparency Drowns in the Pasig

EO 92’s lack of public consultation violates RA 6713’s transparency mandate and PD 1586’s EIS public participation rules. Where’s the input from riverside communities or green groups? And why the hush-hush on Acuzar’s appointment? Legaspi v. CSC (G.R. No. L-72119, 1986) upholds the right to public information—EO 92’s opacity begs for a legal challenge. If this is about public welfare, why hide the script?

4. Fiscal Fiasco and Implementation Nightmares

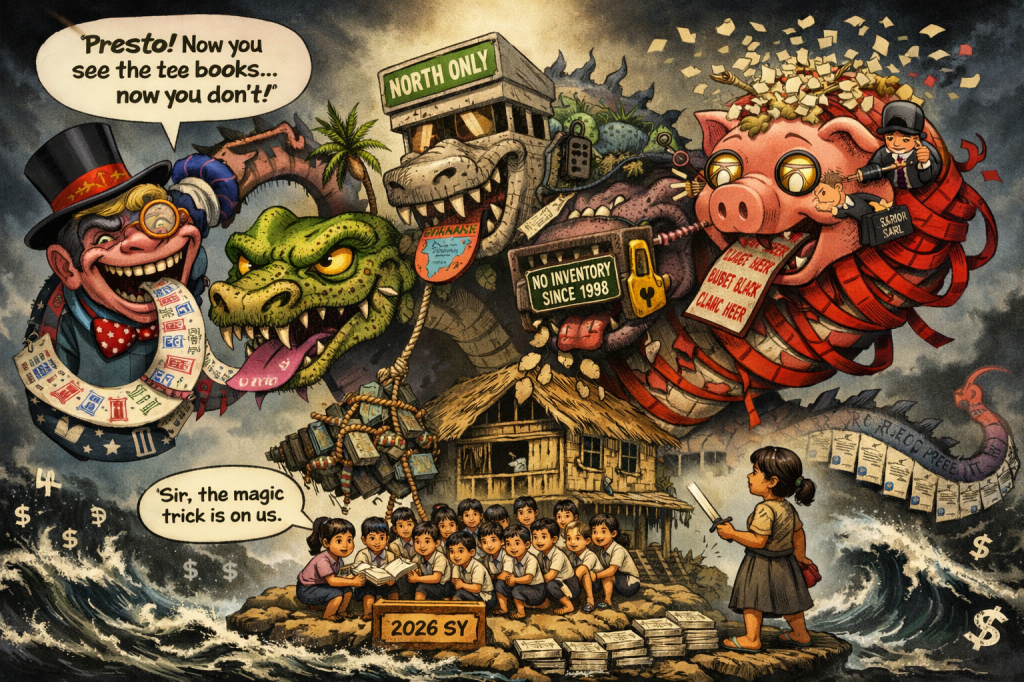

Budget Black Hole: Where’s the Cash?

EO 92 cites Section 93, FY 2025 GAA for funding but offers no specifics. Article VI, Section 25(5) demands clear appropriations—Demetria v. Alba (G.R. No. 71977, 1986) axed vague fund reallocations. A Cabinet-rank adviser’s “emoluments” without a line item? That’s a COA red flag. Why not fund DENR or MMDA instead of this budget sinkhole?

Duplication Déjà Vu: PRRC 2.0?

The PRRC, axed in 2019, won awards yet failed to revive Pasig due to coordination flops. EO 92’s OPAPRR risks the same, duplicating DENR, MMDA, and LLDA mandates. Chavez v. NHA (G.R. No. 164527, 2007) slammed redundant projects as wasteful—why repeat history? The IAC-PRUD’s rejig under a new czar just adds bureaucratic bloat.

Tourism Over Ecology: Selling the River?

EO 92’s focus on parks, bike lanes, and commercial nodes prioritizes glitz over the Pasig’s 65% waste-from-settlers problem. Oposa v. Factoran (G.R. No. 101083, 1993) demands ecological equity, not malls. PD 1067 says easements are for public use, not private leases. Why dress up a dead river instead of tackling its pollution core?

5. Fixing the Fiasco: A Blueprint for Real River Revival

Instead of EO 92’s circus, here’s how to save Pasig without legal or ethical rot:

- Legislate, Don’t Dictate: Pass a law for a Pasig River Authority with clear funding and oversight, dodging Pelaez pitfalls.

- Empower Existing Agencies: Boost DENR, MMDA, and LLDA budgets to enforce RA 9275, RA 9003, and PD 1067.

- Prioritize Ecology: Mandate EIAs under PD 1586, targeting pollution (65% settlers, 35% industry) with PRRC’s proven wastewater strategies.

- Protect Communities: Follow RA 7279 for settler relocation—consult, provide in-city housing, ensure livelihoods.

- Transparent PPPs: Use RA 11966 (PPP Code) for commercial projects with public bidding and audits.

- Independent Oversight: Form a multi-stakeholder board with NGOs and scientists to ensure RA 6713 compliance.

Verdict: Political Pageantry, Not Environmental Salvation

EO 92 is a Marcosian sleight of hand: a feel-good environmental pitch that’s legally wobbly, ethically rotten, and politically driven. Its vague constitutional and GAA reliance courts unconstitutionality, while its overlap with DENR, MMDA, and LLDA spells inefficiency. Acuzar’s appointment screams cronyism, flouting RA 6713, and the tourism obsession betrays Oposa and Manila Bay‘s ecological mandates. With no clear funding, EIS compliance, or settler plan, EO 92 is less about reviving Pasig and more about boosting Marcos’s polls. Why trust this when PRRC’s award-winning efforts still left the river dead? This is political theater, not governance—a river of promises drowning in skepticism.

Final Snark: Want to “Bigyang Buhay” the Pasig? Maybe don’t tap a guy who tanked housing to save a river. Just saying.

Key Citations

Constitutional Provisions

Statutes

- Administrative Code of 1987, Book III, Section 31

- RA 9275 (Clean Water Act)

- RA 9003 (Ecological Solid Waste Management Act)

- RA 7279 (Urban Development and Housing Act)

- PD 1067 (Water Code)

- PD 1586 (EIS System)

- RA 6713 (Code of Conduct)

- RA 11966 (PPP Code)

- RA 7924 (MMDA Charter)

- RA 4850 (LLDA Charter)

Supreme Court Cases

- Pelaez v. Auditor General (1965)

- Biraogo v. Philippine Truth Commission (2010)

- MMDA v. Concerned Residents of Manila Bay (2008)

- Oposa v. Factoran (1993)

- LLDA v. CA (1996)

- Chavez v. PEA (2002)

- Larin v. Executive Secretary (1997)

- Buklod ng Kawaning EIIB v. Zamora (2001)

- Demetria v. Alba (1986)

- Legaspi v. CSC (1986)

- Chavez v. NHA (2007)

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment